A Family Rejects the Industrial Model and Rebuilds Their Farm

Growing up, Will Harris III understood what his path in life was expected to be.

He was the fourth generation of farmers in his family, going back to his great-grandfather, James Edward Harris, who started farming to survive in the chaos after the Civil War. His son Will Carter Harris made the farm into a small business, slaughtering an animal a day and sending the meat into the nearby small town of Bluffton, Ga. on a mule-drawn cart. When Will Bell Harris took the reins, he spun the small business into big business, focusing all the family’s efforts on producing calves to sell to feedlots.

The current Will Harris expected to carry on that legacy, and for many years, he did. He went to the University of Georgia, earned an agricultural-science degree, returned to the farm, and put into practice everything he had learned. That meant routine antibiotics, hormone implants and grain feeding for the cattle, and routine fertilizers and pesticides and herbicides for the fields they sometimes browsed on.

By his 40s, Will Harris was running two profitable, perfect monocultures—one of meat and the other of grass—and doing everything his education and family history told him he should.

And then he stopped, and thought, and changed his mind.

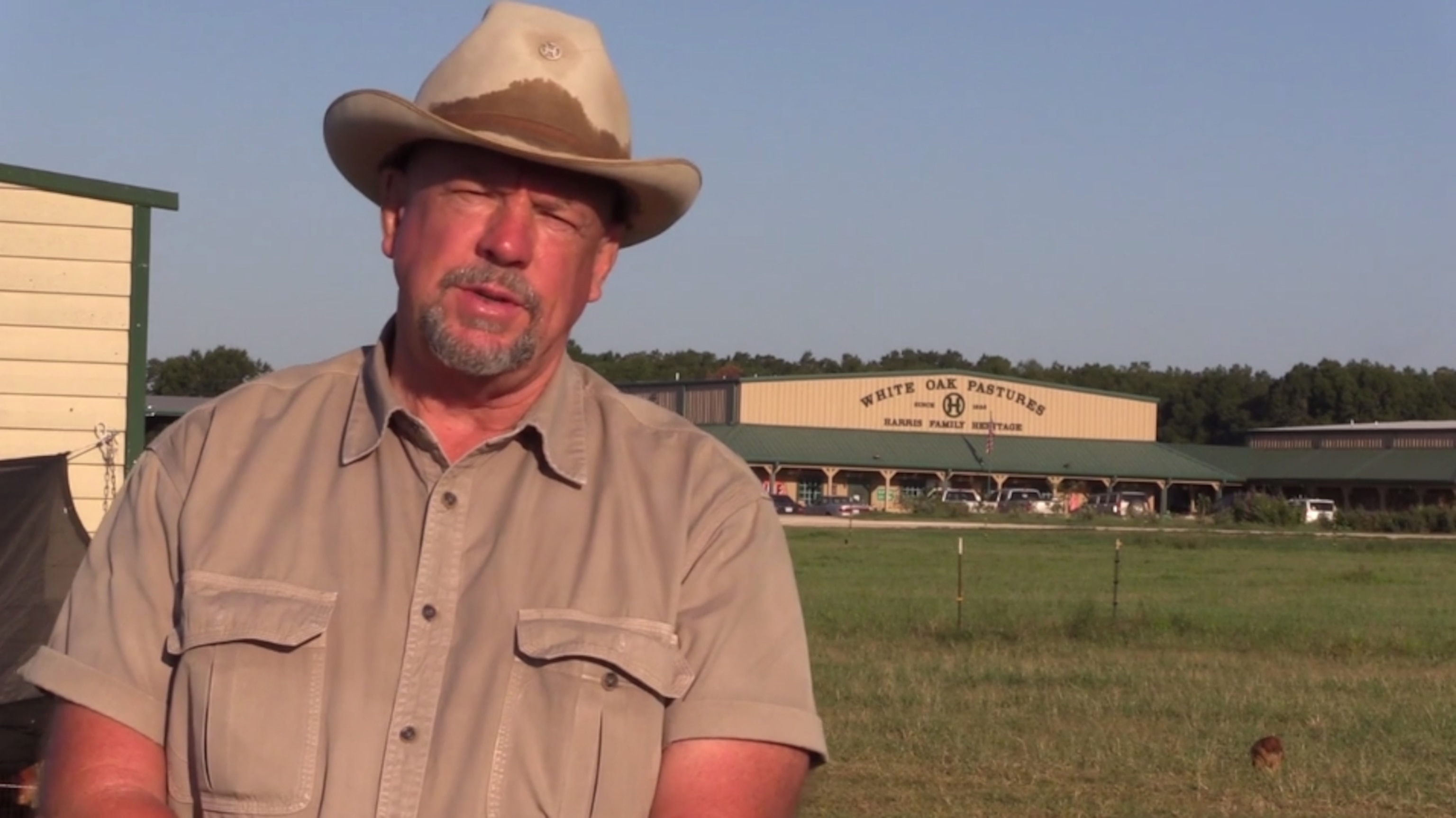

Today, Harris’s White Oak Pastures is the largest USDA certified-organic property in Georgia. It is beautiful, bustling, and prosperous, a thriving rejection of the monoculture mentality. On its 3,000 acres, a mix of owned and leased, he and his 110 employees run 10 different species: cattle, pigs, sheep, goats and rabbits; and chickens, turkeys, geese, ducks and guinea hens. Everything is raised out on the restored pastures, which now support a complex mix of grasses. The animals move through the fields in a carefully plotted rotation, each eating their favorite varieties: first the cattle, then the smaller animals, then the birds, who break up the big animals’ droppings and turn over the earth when they scratch and peck.

The animals spend their entire lives on the farm: It boasts two humane slaughterhouses, one for cattle and one for birds. Determined innovation scavenges every possible byproduct, from saving the cow guts for composting and the rinse water for irrigation to sending the hides for tanning and turning the fat into candles and soaps.

White Oak Pastures is still a family farm: Will’s daughter Jenni is already his second-in-command, and his youngest, Jodi, has started an agritourism program that houses visitors in small cabins in a stand of long-leaf pines. So it’s the perfect place to visit for this year’s World Food Day week, in what the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization has declared the International Year of Family Farming.

If you spend any time reading or thinking about food policy, you’ll soon run up against the contention that only big agribusiness can feed the world, now and as the population grows to the oft-predicted “coming 9 billion” expected to arrive by 2050. In the last few years, economics and analysts — and also farmers and eaters — have begun to push back against that assertion. From the United Nations’ Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, down to small producers who sell at local markets, there is finally recognition that family farms and smallholders have a role in protecting sustainability and feeding the world.

As that discussion moves forward, farms like White Oak Pastures provide a model. It honors its heritage, husbands its animals, preserves its environment, invests in its local economy and provides local employment in a part of a state where there isn’t much going on. And, not incidentally but crucially, produces delicious meat, sold through a CSA, to chefs and supermarkets in the Southeast, and online.

I spent a week at White Oak Pastures earlier this year. Here’s a quick video tour of what a family farm—the kind of family farm that can help feed the world—looks like today.

Meet farmer Will Harris and take a virtual tour of White Oak Pastures.