Giving, grief and the ‘black anaconda’: Inside the world's biggest annual pilgrimage

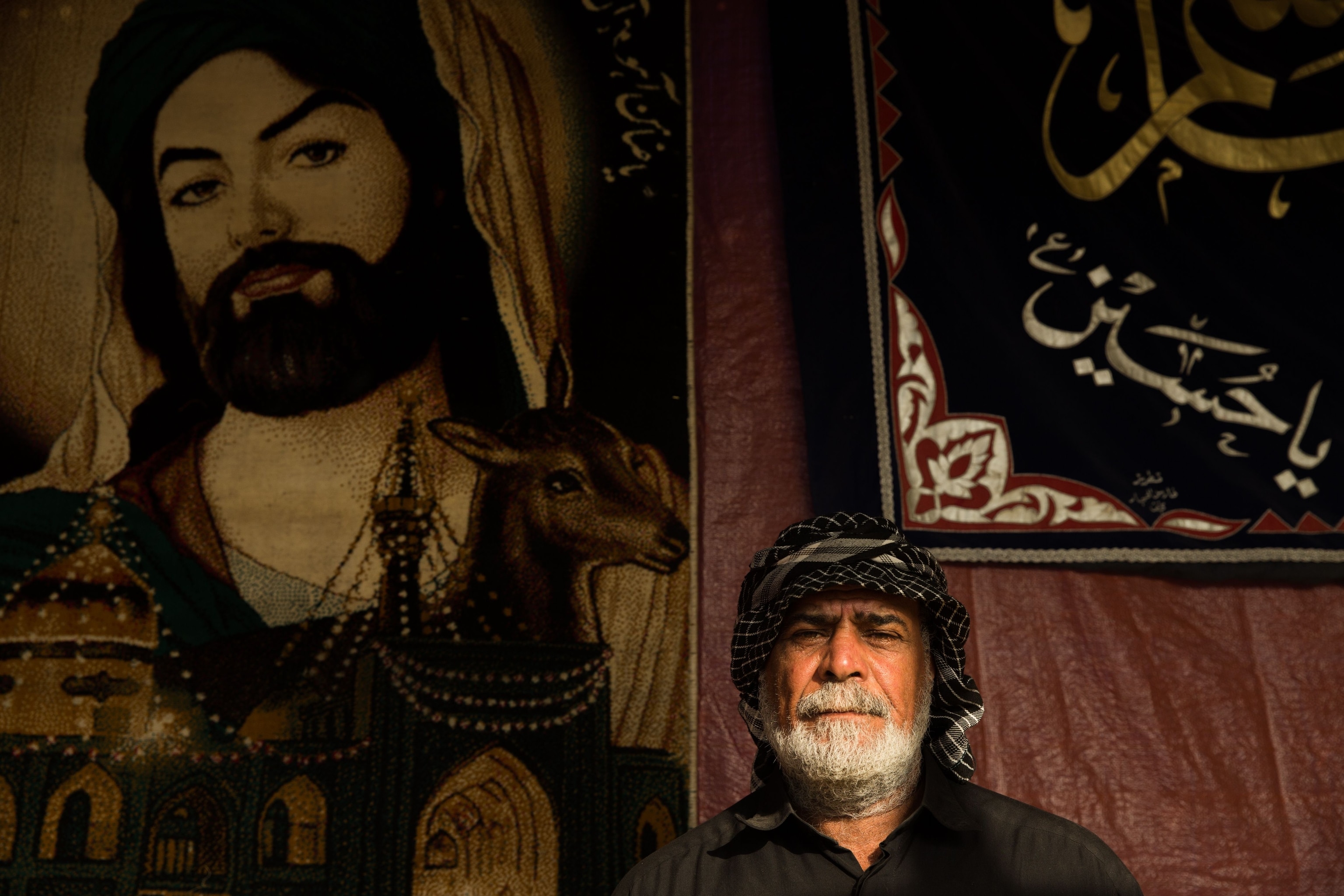

A photographer documents the ‘raw emotion‘ of Arba'een—the movement of millions towards a small city in central Iraq to mourn a man who died almost 1,400 years ago.

The lines start in all corners of the country. People of every age, wearing dark clothes, some holding flags, some dancing, some vocal, some reflective. Groups of men together, groups of women, families. The processions move along roads from every direction towards Karbala—which could be anything from a few hours to over a week’s walk away. Look down on the country from high above and these processions might resemble a kind of slender-limbed starfish, with this city as its centre point. On the ground, the locals use another animal as their analogy for the apparently endless, creeping line: they call it the ‘black anaconda’.

However ominous the nickname, the annual pilgrimage of Arba’een brings a spontaneous and harmonious organization—at colossal scale—to this long war-troubled country. To Shia Muslims, this pilgrimage matters: so much, it attracts between 10 and 20 million every year from around Europe, Asia and the Middle East. All converge on the city of Karbala, in central Iraq, over two days in Autumn. It’s a tight squeeze: Karbala has a resting population of just under 700,000. Compare this to the famous vision of Mecca’s Hajj pilgrimage (2.5 million occupying a city of 1.5 million) and the scale of Arba’een begins to crystallize. It is the biggest annual pilgrimage in the world—by far.

British photographer Jonny Pickup documented Arba’een in October 2019. In recent weeks, political unrest in the capital Baghdad had seen thousands of anti-government protesters occupy the city’s Tahrir square to demonstrate against, amongst other things, Iranian and U.S. political influence. The protests had paused for a fortnight to allow the observance of Arba’een. They’d resume again on October 24; and on November 29, Prime Minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi would resign. But for the moment, focus was on the pilgrimage—at the core of which, Pickup observed, was simply offering what you can. Nothing is paid for; food, drink, accommodation, medical care. During Arba’een, everything is given.

“If you’re a local you might save 10% of your salary to set aside, so when Arba’een comes, you can feed people.” Pickup says. He recalls Iranians whose Ara’been gesture is to collect rubbish on the pilgrim trail. A Kuwaiti company that bought land off one route to build a food warehouse, which it converted into a huge kitchen to cook meals for 10 days over Arba’een—over which it gives away literal tons of chicken, lamb, falafel. “There’s no structure to it. No one is in charge, no government organization. Yet millions of people are fed, watered and sheltered for free. It just happens.”

Two adjacent holy sites in the city of Karbala are this pilgrimage’s destination: the Abu Fadhl Al-Abbas shrine, and the Imam Husayn shrine. The dark dress worn by many of the pilgrims (hence, ‘black anaconda’) acknowledges that Arba’een is a festival of mourning, and one whose complex origins reach into the modern age from nearly 1,400 years ago. There are other signal colors, too: green is the colour of Muhammad. Red is the colour of love, of passion. Of blood.

The origins of Arba’een

All are symbolic in the story of Al-Husayn ibn Ali, the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad. Husayn was critical of the ruler of the Umayyad caliphate, a leadership that had ordered the assassination of Husayn’s father for dissent. Heading for the city of Kūfah to assist in an uprising, Husayn was intercepted by an army of 4,000 soldiers, sent by the governor of Iraq on behalf of the Umayyad. After a battle, he was killed in Karbala, on the banks of the Euphrates, on 10 October 680. The focal point of Arba’een is the Husayn Shrine—believed to mark the place where he fell. The nearby Al-Abbas mosque and shrine commemorates Al-Abbas ibn Ali, a warrior who fought and died alongside his half-brother Husayn. Both are considered martyrs by Shi'ites in the face of an opposing oppression, and their deaths are marked with Ashura, the 10th day of the first month in the Islamic calendar. Traditionally, Arba’een takes place forty days later. It takes many little less than that to make their own observance.

People come from far away for Arba'een. From Malaysia, from Afghanistan, Britain and many, many people from Iran—everywhere there is a Shia Muslim community. Many have little money. Fakhrnasim has spent 15 days journeying to Iraq from Pakistan. A cloth seller, it has cost him 60,000 rupees (about $220)—a huge part of his annual income—and over a month of the time he has to make it. He is one of 57 just from his village. His reasoning: “We love Husayn. We do this journey, it’s no problem. He saved us.” Another, who Pickup gets chatting to in a Jordanian airport, is English and is organising groups from London to travel to Iraq for Arba’een. Some of the groups number over 300 people.

“When you’re talking about millions of people—15 million, 16 million—it becomes abstract. You can’t picture that amount,” Pickup says. “Then when you really start to see the numbers… it is never-ending. When we drove out of Baghdad, even days before Arba’een itself, the lines were apparent, right outside the city. It’s maybe four hours' drive. The line was consistent the whole way. And it’s the same in every direction, every road, every back street.”

Recent history

Echoing these original tensions in a more modern scene, Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship—fearing uprising amongst the amassed crowds—made public observance of this Shia pilgrimage illegal. Dissenters were imprisoned, or executed. Police would dress in pilgrims’ clothes to catch them. Following the toppling of Saddam, chaotic years of conflict dominated by the threat of Al Qaeda and ISIS made observing Arba’een a mortal risk. A network of secret signs were employed—a white arrow or cross for safe, or not—indicating back streets off the main routes. Such subterfuge now unnecessary, in its place there are now public swimming pools and shisha houses lining formerly secret pilgrim paths.

Today, despite Arba’een exhibiting the confidence of a people free to articulate their beliefs, there are still many complications. The shadow of the recent protests, but also of years of violence that have kept Iraq in the headlines for all the wrong reasons.

The state-sponsored Hashd Al Shaabi militia, or Popular Mobilisation Force (PMF)— revered by many pilgrims for their role in the defeat of ISIS—are reminders of violent times all too recent. Their march at Arba'een, signified by their green berets, and the line of war widows who follow them, are a solemn presence. So too are the many who hold photographs of loved ones lost in recent conflict. One man, 60 year-old Naim, carries the image of his son Amer, killed by ISIS in 2015. He wants his son to see Husayn’s shrine. Not even death will stop him, he says.

‘Raw emotion’

As the culmination of Arba'een approaches, inside Karbala the crowds grow. Over a week the shrine’s footfall builds and builds, until the holy dates of 19 and 20 October. The busiest times are the early hours, 3-4 in the morning, when the day’s heat has dissipated, making the extraordinary crowds more bearable. There is more of an intensity, as well as, according to Pickup, an outpouring of collective grief. “Arba’een is emotion. Shi’ites feel a lot of sadness—firstly that Husayn was martyred, and then for the women and children of his family, who were paraded across the middle east, and humiliated. They hold them very dear.”

The two shrines sit hundreds of metres apart: groups register, move in a long line into one, then proceed to the next. Men and women segregate according to Islamic custom. People weep, cry, clutch their chests. Some read the Quran, some pray. Many —hundreds at a time—try to touch the tombs at the centre of the shrines. Physical contact; the end of the pilgrimage.

It is unknown how much of Husayn’s body is buried here; both he and his followers were mutilated and dismembered, their body parts ‘cast around in the dirt.’ Some pilgrims symbolically cover themselves in dust, their t-shirts streaked with pale, sandy marks, some in the shape of hands.

Others find more physical ways to be close to their martyr, through symbolic suffering, or penance: flagellation. It isn’t encouraged, but it happens. Most notable is a ritualistic beating of the face amongst some pilgrims from the south as they walk through the shrine; punishment for ancestors who didn’t come to Husayn’s aid.

A mobile cart pushed by the crowd pumps out a techno-style beat, over which Arabic poetry is read out by a man with a microphone. Everyone down below dances, hands in the air. A British doctor has travelled to Iraq to work in a medical centre here. His Arba’een gesture, his giving, is to offer free medical care to those on the pilgrimage. Many do the walk barefoot, so blisters and bad feet are a common complaint. But so are injuries to the ribs: from crushing, in the final squeeze to the shrine. The crowds are a risk: just weeks earlier during Ashura in Karbala an accident during the ‘Tuwairij run’ ritual saw 31 killed and 100 injured in a stampede.

“The feeling inside that inner shrine—it is such an overwhelming, condensed emotion in that room. It’s unbelievable,” says Pickup. “There’s an inner passage, you’re in this queue of people, you start to lose your ability to navigate. You’re just in this crowd, being pushed along. Then you slowly get into this inner space, people just climbing over each other, doing anything to touch this tomb. People shouting ‘Husayn, Husayn.’ Chaotic, but also has a kind of beauty to it. Such raw emotion.”

Back to life

Then, finally, rest. On the streets, “you see sleeping bodies everywhere,” Pickup says. “In construction sites, stacked in empty building blocks, on the streets, on rooftops.” Eventually, piled into trucks, buses, cars, people begin to make their way back to their own individual lives—many of which are lived with continuing modern unrest.

Usama, from Baghdad, sees the principal of protests in his home city as a mirror for the meaning of this pilgrimage: “What Husayn did is similar to what the young people are doing now,” he says. “If there were protests now, I wouldn’t be here. I’d be there. What happened [in Karbala] 1,400 years ago is happening now again.”

But amidst the pilgrimage itself, despite scattered reports of tensions the abiding mood is one of collective, emotional worship. “During my whole time there I didn’t see one problem, no rioting, not one aggressive thing.” says Jonny Pickup.

Such is the scale of collective generosity that on December 14 2019, UNESCO added the provision of services and hospitality during Arba’een to its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Mir, from India, travelled from India as part of a group of 12. “I feel so touched when I see the way people give, irrespective of creed, religion, race or color.” he says. “It transcends the problems of humanity. People care for each other. That’s what Arba’een means.”

This article was adapted from the National Geographic U.K. website.