Carb Conundrum: Can Bialys Survive in a Bagel World?

On a recent trip to Sadelle’s, a modern Jewish deli in the SoHo neighborhood of Manhattan, I got a sudden craving for a bialy. As I ogled bagels, stacked and Instagram-ready on wooden dowels, I asked the hostess with gleeful anticipation if they had my favorite Jewish bread. My question was met with a blank stare.

“A what?” she asked.

“A bialy,” I replied.

“What’s that?”

Oy, I thought.

To be fair, nowhere is it written that a Jewish deli is obligated to sell bialys, much less know what they are. But I’m someone who laments the dearth of good bialys in the world, and I worry about their survival.

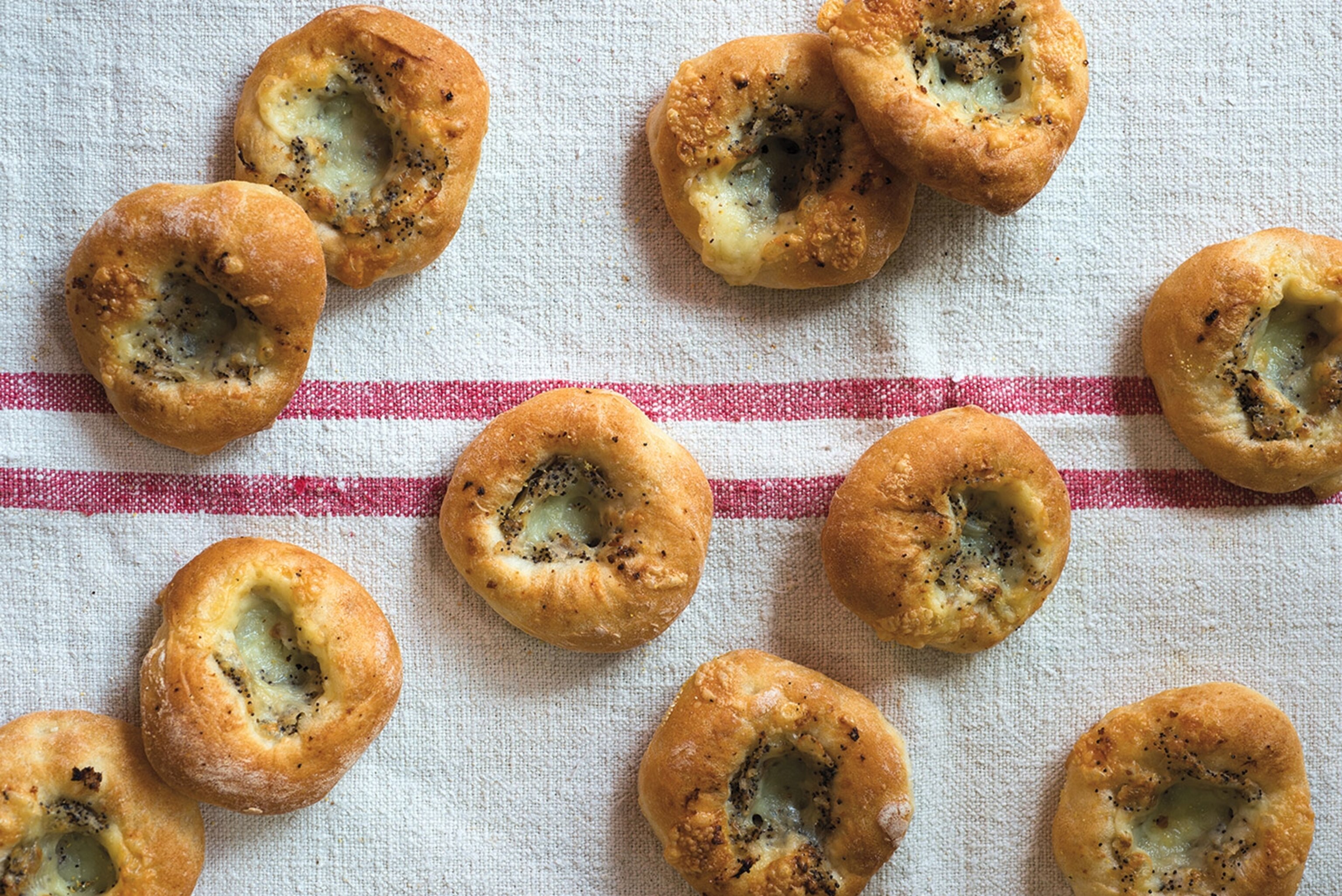

First things first: a bialy is not a bagel. A bialy has no hole. It is baked; not boiled and then baked, like a bagel. It is slightly sour, chewy, and savory. And it originated in Bialystok, Poland, emigrating to New York City with Polish Jews sometime in the early 1900s.

I grew up in Southern California, the daughter of Brooklyn Jews, so I claim a genetic affinity for the crusty roll with an onion glory hole. I also believe it’s far superior to the bagel. (Historically, bialys have onion and poppy seed centers, but now to the chagrin of many a bialy-purist, they can be found with raisins, blueberries, or even sun-dried tomatoes.)

Yet they are a hard sell. While airy, crusty, and flavorful bialys continue to languish as a cult food—a distant memory of the past from a far away place—doughy, bland bagels have become as American as apple pie.

“It’s the symbolism that Jews are tough and stubborn in the face of adversity, the symbolism of the onion center that makes you cry when you chop them, like the tears of the all the Jews. That’s the beauty of something as simple as flour, water, yeast, and salt.”—Mark Strausman, Freds at Barneys New York, on the bialy

This year, New York’s Lower East Side Jewish food landmark Kossar’s celebrates 80 years in business. It just re-launched its brand with new owners, so it may be time to consider whether bialys can survive in a world where the bagel is king.

The de facto leader of bialy boosters is New York native Mimi Sheraton, the award-winning journalist who in her seminal book The Bialy Eaters; The Story of a Bread and a Lost World admits that her late husband diagnosed her with “Compulsive Obsessive Bialy Disorder (COBD)”.

Sheraton, who recently celebrated her 90th birthday (with fresh-baked bialys, of course) tells me she is not sanguine about the current state of the bialy. “Bialys are poor ugly things,” she says. “They should be tough, with a poverty-stricken appeal, with charred or even burned onions; maybe the young people don’t have a taste for it.”

A Bread of Humble, Yet Historic Proportions

To understand the allure of the bialy, one must learn its origins, Sheraton believes.

Bialys were the food of everyday meals for everyone in Bialystok, Poland, whose population was over 70 percent Jewish. Over a seven-year period in the 1990s, she interviewed bialystokers all over the world who recalled the kuchen bakeries on neighborhood corners; the women who sold the warm rolls out of big woven baskets, how they ate them with smoked fish, soup, potatoes or even halvah (a soft, sesame paste candy.)

Bialys not only provided sustenance to rich and poor, but also a uniquely Jewish cuisine that thrived in a country that was not often friendly to Jews. In fact, before World War II, Bialystok was a dynamic Jewish capital that had a population of over 50,000 Jews.

But like most stories that involve WWII and Jews, the ending is not happy. In his book Inside the Jewish Bakery; Recipes and Memories from the Golden Age of Jewish Baking, Stanley Ginsberg writes, “…the kuchen’s death (in Bialystok) can be pinpointed precisely to June 27, 1941, the day the Nazis locked anywhere from 800 to 3,000 (estimates vary) Bialystok Jews in the main synagogue and set the building afire.” During the next several years, Ginsberg explains, Jews were forced into a ghetto or shot in the streets. Those that didn’t escape were eventually transported to Nazi concentration camps.

Today in Bialystok, you will find neither bialys, nor any remnants of the Jewish bakers who lived there. But there was a time in New York when there were enough bialy bakers on the Lower East Side to form a union. The bakers would hand shape the rolls with the requisite center depression, bake them to a precise crispiness (i.e., almost burnt) and achieve that magic balance of texture and onion flavor.

Keepers of the Kuchen

According to Niki Russ Federman, a fourth-generation owner of the 102-year-old Russ & Daughters restaurants and stores, “Bialys are the underdog of Jewish breads.” Even as her family company expands with new cafes and a bakery, she admits bagels outsell bialys at a rate of about three to one.

Noah Bernamoff, one of the founders New York-based Mile End Delis and Black Seed Bagels, says he sells “maybe five percent bialys, and most of our bialy customers are from an older generation.”

Bernamoff, who is from Montreal and didn’t eat his first bialy until he moved to New York, says his mission is to keep Jewish food relevant. But even if he could open 15 or 20 locations, “I don’t even know if we’d be scratching the surface to keep these food traditions alive. It’s kind of depressing and sometimes it feels like we’ve taken on this huge uphill challenge.”

Bialys are often hard to come by outside of New York. At Zingerman’s Bakehouse in Ann Arbor, Michigan, they only bake five or six-dozen bialys a week. But managing partner Frank Carollo says he’s committed. “Bialys have an incredible story and we’ll continue to honor it.”

At Wise & Sons Delicatessen in San Francisco, bialys have always been front and center on the menu, says co-founder Evan Bloom. Bloom, like me, grew up in Los Angeles with a dad who loved bialys. He prefers them to the bagel; they are easier to produce and make great sandwich bread. “Now we’re seeing families bring their kids into the deli and we get to cultivate a new generation of bialy eaters,” he said.

Learning and Re-Learning History

But even as the stubborn bakers and restaurateurs keep hope alive, there’s still a huge learning curve. For example, in New York, you used to be able to get a bialy at any bodega, now with the city’s gentrification, the bodegas are gone, and with them, the knowledge of what a bialy is has gone, too.

You’ll find one of the best bialys in Los Angeles in Venice at Gjusta—a kind of food nirvana of takeaway delis— but when you read the Yelp reviews, the customers call them bagels.

Kossar’s new owner, Evan Gingier, says the restaurant has a re-education task to raise the bialy’s national profile, so part of its marketing efforts include a comic man-on-the-street video asking random New Yorkers, “What’s a Bialy?” The answers aren’t encouraging. Is it a car, a roller coaster, a new dog breed? You get the picture.

Even Mark Strausman, the Executive Chef of Freds at Barneys New York restaurants, which serves bialys on Sundays at all Freds locations in Chicago, New York and Beverly Hills, told me he recently had a distressing moment in his own kitchen. When one of his chefs asked him, “What’s a bialy?” He says he told her, “I’ll explain it to you, but I need to walk away for a moment.”

Strausman was a boy from Queens, who long before he become an acclaimed chef, wanted a job at the neighborhood bagel store. So he tells me he’ll continue to make bialys as long as he can (And by the way, Strausman’s bialys are Mimi Sheraton-approved.)

“For me it’s about not letting it die—so my kids and my grandkids will know what it is,” he says. “But more importantly it’s the art of the bialy. It’s the symbolism that Jews are tough and stubborn in the face of adversity, the symbolism of the onion center that makes you cry when you chop them, like the tears of the all the Jews. That’s the beauty of something as simple as flour, water, yeast, and salt.”

Want to take a crack at baking your own bialy? Here’s a recipe from The Hot Bread Kitchen Cookbook. Copyright © 2015 by Jessamyn Waldman Rodriguez. Published by Clarkson Potter/Publishers, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.

Traditional Onion Bialy

Bialy Dough

1⅓ cups/320 g lukewarm water

3 ½ cups plus 2 tablespoons/

465 g bread flour, plus more for shaping

½ cup plus 2 tablespoons/150 g (risen and deflated) pâte fermentée (recipe follows) cut into walnut-size pieces

¾ teaspoon active dry yeast

1 tablespoon kosher salt

Filling

3 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

4 medium yellow onions, finely diced (6 cups/900 g)

½ cup/60 g fine dried bread crumbs (page 281)

1 tablespoons poppy seeds

½ teaspoon kosher salt

- To make the bialy dough: Put the water and flour in the bowl of a stand mixer fitted with a dough hook, and mix for 2 minutes. Let rest for 20 minutes.

- Add the pâte fermentée, yeast, and salt and mix on low speed until the dry ingredients are completely combined. Add a little more water if this hasn’t happened in 3 minutes. Increase the speed to medium to medium-high and mix until the dough is smooth, pulls away from the sides of the bowl (and leaves the sides clean), has a bit of shine, and makes a slapping noise against the sides of the bowl, 5 to 7 minutes. Do the windowpane test to check to see if the gluten is fully developed.

- Dust a clean bowl lightly with flour and transfer the dough to it. Cover the bowl with plastic wrap (or put the whole bowl in a large plastic bag) and let stand at room temperature until doubled in volume, about 1 hour and 30 minutes.

- Meanwhile, to prepare the filling: Heat the oil in a large skillet set over medium-low heat. Add the onions and cook, stirring now and then, until they just begin to brown and have reduced to about a third of their original volume, about 20 minutes. Transfer the onions to a bowl and stir in the bread crumbs, poppy seeds, and salt. Set aside to cool.

- Transfer the dough to a lightly floured surface. Divide the dough into 12 equal pieces (each weighing about 2 ¾ ounces/80 g). Form each piece into a small bun cover with plastic wrap, and let rest for 5 minutes. Proceeding in the same order in which you shaped the pieces into balls, flatten each ball with the heel of your hand into a disk about 4 inches/10 cm in diameter.

- Line the backs of 2 rimmed baking sheets with parchment. Put the disks on the baking sheets, evenly spaced and at least an inch apart. Loosely cover with plastic wrap. Let stand until the rolls are very soft and hold an indentation when you touch them lightly, 1 hour to 1 hour and 30 minutes.

- Put a pizza stone on the middle rack of the oven and preheat to 500 F/260 C. Let the stone heat up for at least 30 minutes.

- Uncover the bialys and, using the pads of both your index and middle fingertips, make a depression in the center of each disk of dough. Put about 2 tablespoons filling in the center of each bialy, spreading it out so it fills the center.

- In one swift motion, slide the bialys and the parchment onto the pizza stone. Bake until golden brown, 12 to 15 minutes. Transfer to a wire rack to cool for a few minutes (discard the parchment).

- Serve immediately. Leftovers can be kept in an airtight plastic bag at room temperature for 2 days.

Pâte Fermentée

Makes about 1 1/4 cups/300 g (risen and deflated)

Pâte fermentée is an ingredient in many recipes in the lean and enriched doughs chapters. You need to make it eight to twenty-four hours before you bake your bread. This extra step extends fermentation time and allows you to achieve a light, flavorful loaf with less yeast. Pâte fermentée contains the ingredients of simple French bread dough—flour, water, yeast, and salt—so, in a pinch, you could bake and eat it. Unlike other types of pre-ferments, such as levain, pâte fermentée does not impart a sour flavor to the bread. Instead it adds depth of flavor and extends the shelf life of your bread. If you make bread often, you can save the trimmings from lean doughs to use in your pâte fermentée.

½ cup plus 1 teaspoon/120 g lukewarm water

⅔ teaspoon active dry yeast

1⅓ cups plus 1 tablespoon/180 g bread flour

1 teaspoon kosher salt

- Put the water and yeast in the bowl of a stand mixer fitted with a dough hook, then add the flour and salt. Mix on low speed for 2 minutes until combined into a shaggy dough. Cover the bowl with plastic wrap and let stand at room temperature for 30 minutes.

- Refrigerate the mixture for a minimum of 8 hours and a maximum of 24. (There is no need to return it to room temperature before using.)

- If you’re measuring the pâte fermentée rather than weighing it, be sure to deflate it with a wooden spoon or with floured fingertips before measuring.

Stacie Stukin is the West Coast Editor of Naturally, Danny Seo magazine and also writes about food, health and design for, among others, the New York Times, W Magazine, and the Los Angeles Times. Her favorite bialy is from Freds at Barneys Beverly Hills. Find her on Twitter.