Clean Your Plate: Getting a Handle on Food Waste

The food-saving ideas of the past may not be so quaint, considering that we waste about 30 percent of the food we produce on this planet.

The Clean Plate Club is a suspiciously elusive organization once cited by mothers urging unhappy kids to spoon up their pea soup or polish off their broccoli. And it owes its existence to World War I.

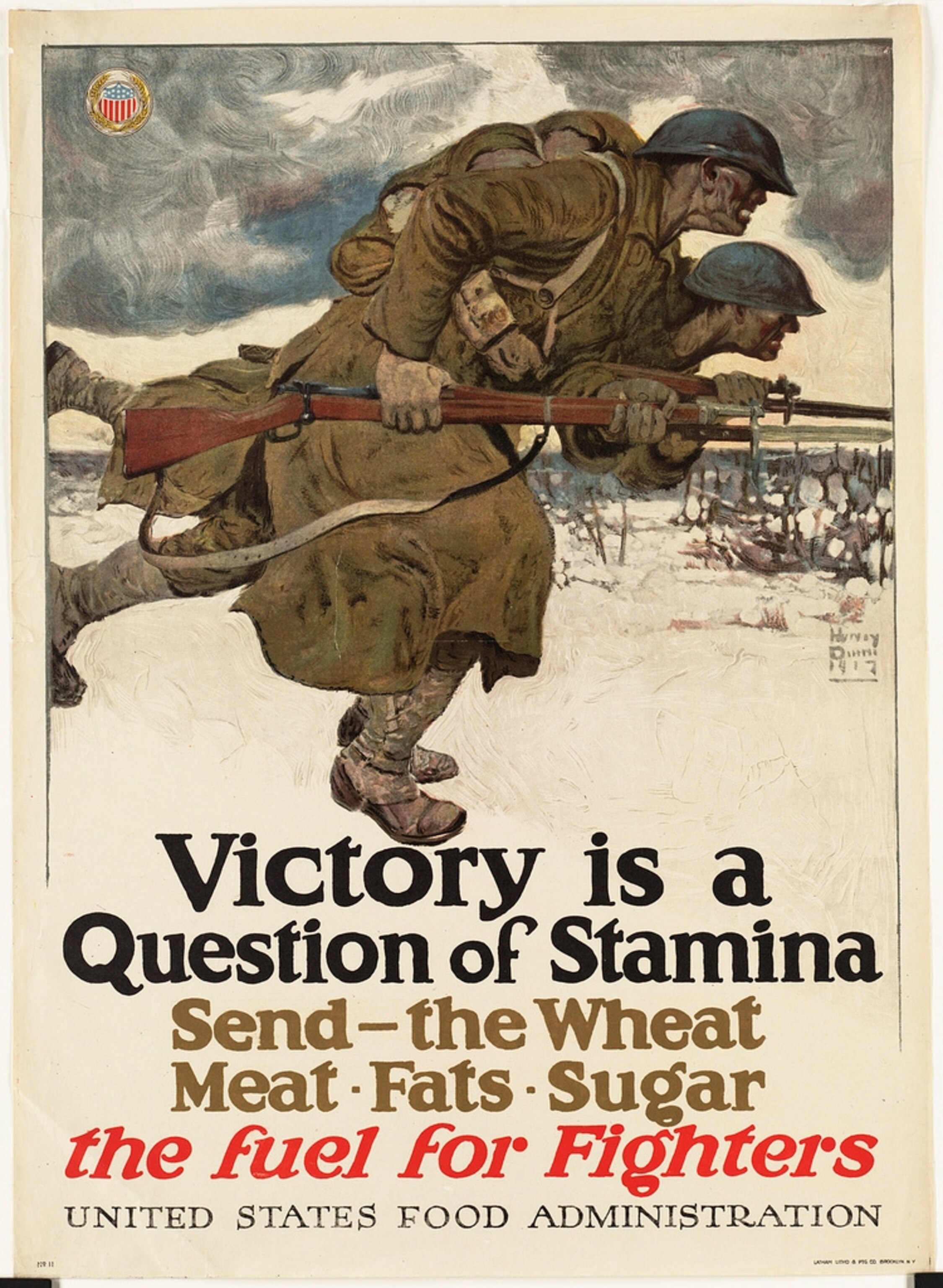

In 1917, the government, worried about wartime food shortages, passed the Food and Fuel Control Act, giving President Woodrow Wilson the power to “regulate the distribution, export, import, purchase and storage of food.” Wilson used his new mandate to create the U.S. Food Administration under the direction of Herbert Hoover, who – vowing that “Food will win the war” – set about convincing Americans to conserve. Citizens were urged to sign pledge cards, swearing to forgo waste by adopting the “doctrine of the clean plate.”

The food-saving, clean-plate idea was revived in 1947 after World War II, when Harry Truman called upon Americans to curb waste in order to help send food to the starving post-war populace of Europe. Hundreds of elementary schools promptly formed Clean Plate Clubs. Finishing one’s fish sticks became a patriotic duty. The truly dedicated promised to give up eating between meals.

The virtue of the clean plate has such a grip on the American psyche that it still survives today. A 2013 study in the journal Pediatrics found that up to two-thirds of American parents still urge their kids to finish everything on their plates – a practice which, in the age of super-sized portions and a climbing obesity rate, has come back to bite us. A better approach, nutritionists explain, is not to put too much on the plate in the first place – and to let kids adjust to their own internal appetite cues.

Within the bounds of dietary common sense, however, the clean plate isn’t a bad idea. A winner of the Short Film Challenge at this year’s Sundance Festival shows just why. “Man in the Maze” by Phil Buccellato and Jesse Ash of New York City’s Greener Media is a compelling eight-minute documentary on the mindboggling extent of modern food waste. Each year some 2.8 trillion tons of food–30 percent–never make it to the dinner table. (In the United States, the waste figure is as high as 40 percent.)

Food waste starts on the farm, where a lot of the harvest never gets out of the field. Some of this is due to the slings and arrows that are a farmer’s lot–pests, disease, and lousy weather. Sometimes, however, due to plunging market prices, growers decide that the crop simply isn’t worth the expense of harvest or transport – which leads, in “Man in the Maze,” to the depressing sight of truckloads of ripe tomatoes being tipped into a landfill at the Mexico-U.S. border. Typically, according to a report by the National Research Defense Council, about 7 percent of American fields are not harvested each year, among these some 100,000 acres of vegetables.

Post-harvest, a significant proportion of crops fall to culling – that is, the elimination of anything that doesn’t meet specified quality or appearance standards, being too small, too lumpy, too spotty, or otherwise flawed. Estimates vary, but researchers suggest that anywhere between 25 percent and 40 percent of fruits and vegetables are wasted because they don’t measure up to established standards of food pulchritude. (Also see The Plate’s Pears Like Little Buddhas.)

Processing (primarily trimming) accounts for further food waste – European studies estimate anywhere from a 16 to 39 percent loss – and in potato processing, according to one plant engineer, about half the bulk of all potatoes lands in the trash. Distribution creates further problems, especially for perishable foods that must be stored under temperature-controlled conditions. One industry consultant found that up to one in every seven truckloads of perishables delivered to supermarkets arrives in bad shape and is thrown away.

Supermarkets account for another wave of waste, mostly perishables and unsold stock, in quantities that add up to an estimated annual 43 billion pounds; and each year households and food service operations (restaurants, cafeterias, and fast-food chains) toss out a collective 86 billion pounds of unwanted food. Much of this last comes from non-clean-plate diners who, on average, leave 17 percent of their meals uneaten and then decline to take their leftovers home.

Finally, families – even the thriftiest of us – tend to be wasteful. American families, on average, chuck about 25 percent of the food they buy. You can see how much food this looks like over at our photo blog, Proof. Common reasons are spoilage – due to poor storage, over-buying, or the fact that we’ve forgotten that we have it in the refrigerator; and to confusion over label dates, which leads us to throw food out prematurely. (The “use by” dates stamped on food products are not, as many assume, safety regulations, but manufacturers’ suggestions for date of peak quality.)

Furthermore, waste-wise, over the past decades, we’ve gotten worse. Waste these days is up 50 percent from what it was in the 1970s. According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, today we waste, on average, 38 percent of our grains, 50 percent of seafood, 52 percent of fruits and vegetables, 22 percent of meats, and 20 percent of milk. In a world where 805 million people worldwide go to bed hungry and one out of every six Americans has no secure supply of something to eat, that’s an appalling amount of lost food.

Food recovery programs now attempt to collect edible “waste” food and redistribute it to those who need it, often through local Food Banks – though to date only about 10 percent of waste food is effectively recovered. Other solutions to the waste problem include municipal composting, concurrent harvesting – in which sub-standard, but edible, crops are set aside for non-commercial distribution, and improvements in the “cold chain” – that is, the temperature-controlled supply network by which perishable foods are transported from source to supermarket.

The bright side: food waste is increasingly a matter of national and international concern. In the US, some cities and states – among them Vermont, Connecticut, San Francisco, Seattle, and New York City – now require food waste recycling; and programs such as the Food Waste Reduction Alliance and the Environmental Protection Agency’s Food Recovery Challenge seek to both reduce and recycle food waste and to re-distribute usable but about-to-be-discarded food to those who need it. The French Ministry of Agriculture, Food Industry, and Forestry recently launched a National Pact Against Food Waste, with the goal of reducing food waste in France by 50 percent by 2025. Great Britain’s “Love Food Hate Waste” program – which aims at establishing a “zero waste economy” – has reduced British food waste by 21 percent over the past five years.

At the grassroots level, the most radical of food-waste fighters practice freeganism – a portmanteau word combining “free” and “vegan” – in which participants pursue an anti-consumerist, off-the-grid lifestyle that involves foraging, urban gardening, and dumpster diving to retrieve discarded goods and waste food. Admittedly, this isn’t for everyone. (For other solutions, see: One-Third of Food is Lost or Wasted: What Can Be Done from our Future of Food series and Are Fly Farms a Solution to Food Waste?

The 2.8 trillion tons of food we throw away is enough to feed three billion people – and, with the world population slated to hit nine billion by 2050, we’re going to need it. “Willful waste makes woeful want” is a proverb that dates back at least to the 16th century. It’s still right on.