Climate disasters threaten irreplaceable works of art. Museums have a battle plan.

Curators and conservators are finding innovative solutions to protect our history from disaster. Will some be destroyed despite their best efforts?

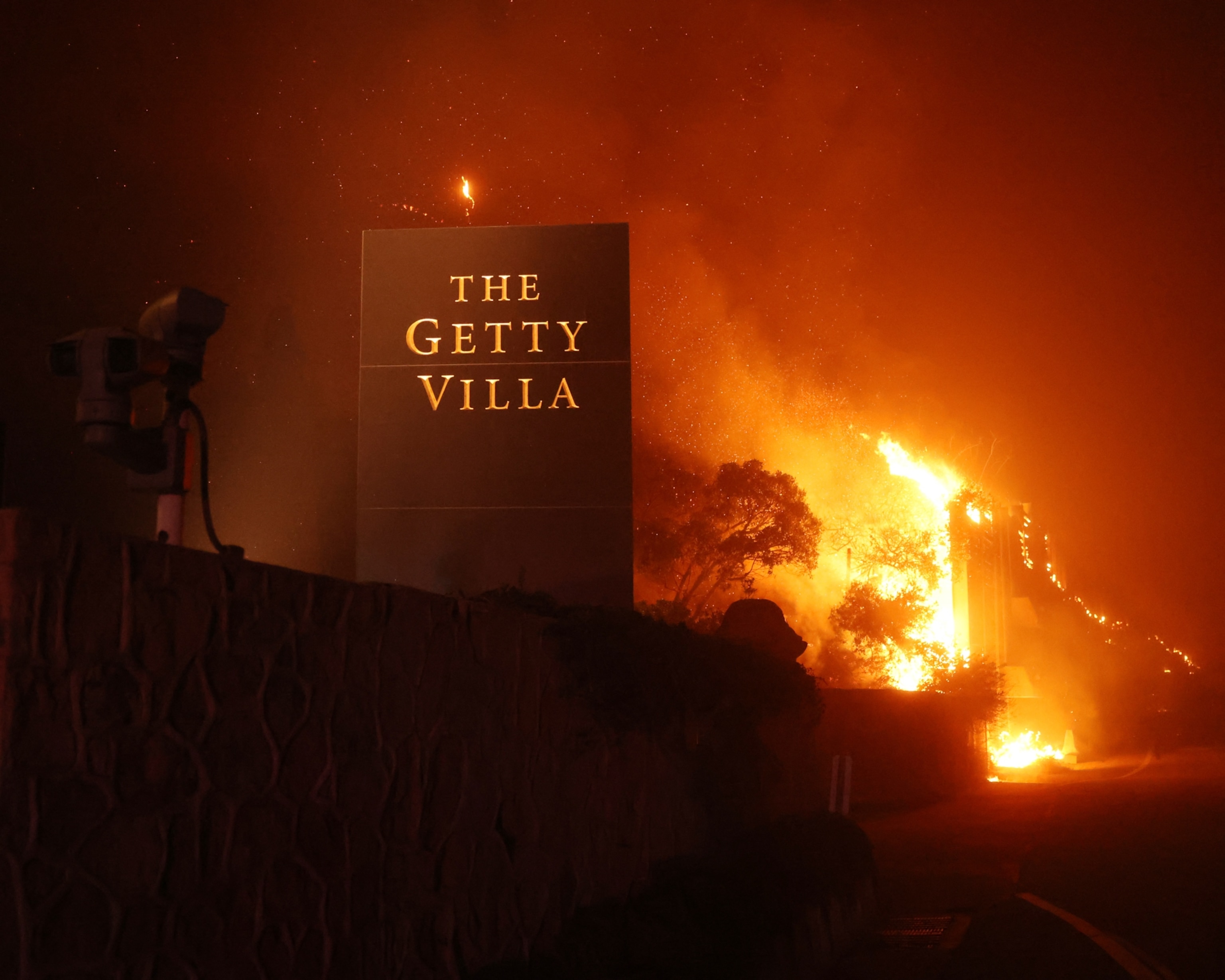

A boy stands in contrapposto, leaning his weight onto his right leg, one hand lifted to his head, as though to adjust his delicate olive wreath. His expression is noble and calm, the very picture of composed dignity. This bronze statue of this young Olympian is dated between 300–100 BC, one of the few life-sized Greek bronzes to have survived thousands of years into the 21st century. But in January 2025, the Statue of a Victorious Youth was nearly lost, consumed by the Palisades Fire, which roared through Los Angeles County destroying close to 7,000 structures.

Housed inside the Getty Villa in Los Angeles, Victorious Youth managed to survive. As the fire consumed thousands of structures, including the Getty’s immediate neighbors, the museum stood virtually untouched, the collection inside was undamaged.

“L.A. has almost all the disaster typologies,” explains Camille Kirk, sustainability director at Getty. “We even have hurricanes from time to time. The disasters we see are not purely climate change; they are exacerbated by climate change, but they are also part of the long human history of the place.”

When the Villa was built, it was constructed with this knowledge in mind. The building was designed to withstand earthquakes, fire, and flooding. It escaped the Palisades Fire because of its irrigation system, which was activated early on, and its double-walled construction, which kept the art safe from heat damage. Nor did smoke penetrate the galleries; special air handling systems were already in place to seal off each room. It wasn’t luck that saved the Victorious Youth. It was forethought.

As climate disasters become more frequent, institutions like the Getty and governments around the globe are having to grapple with the possibility that humanity’s great treasures could be damaged or destroyed despite their best efforts to protect them.

Curators and conservators, tasked with protecting our cultural memory, are always creating new solutions for fresh problems. Some institutions, like the Getty Villa and the Charleston Museum in South Carolina, credit their predecessors’ foresight in designing buildings strong enough to weather our ongoing climate catastrophes, while others, including the Mauritshuis in The Hague, are putting stock in their teams’ ability to adapt. And it’s not just museums: from historic city parks to famous clipper ships, there are thousands of significant sites at risk.

From ancient rock art to Dutch Golden Age paintings, great cultural works are vulnerable to the chaotic whims of the Anthropocene. Some are threatened by flooding, others by fire— but the throughline connecting them is what we stand to lose: the most potent evidence of human ingenuity and creativity, the story of our shared artistic past, perhaps even what makes us human at all.

Some can’t be saved. Cave paintings will continue to flake from the walls, and ancient cities will eventually crumble to dust. There’s truly no one-size-fits-all solution; the stewards of each site must assess the threats to their collection and try to prepare for all probable disasters. But the curators, conservators and researchers who document cultural climate-induced loss do more than sound the alarm, they are also working to best preserve the objects that can be saved. “We know from psychology research that there’s been a rise in anxious concern about climate change,” says Kirk, who suggests that “some of the anxiety about climate change might be rooted in this inchoate fear that we might be losing beauty from the world.”

“What happens if we lose archeological sites, built heritage, objects that tell stories about us as humans? We lose our stories. We lose knowledge about us. Our past selves, our present selves, our future selves,” says Kirk. “The loss of culture is a loss of identity.” These are the climate-related challenges faced by the conservators of cultural sites and works of art—some can be preserved for future generations while others may be too vulnerable to climate chaos to save.

Protecting a famous Vermeer painting from the threat of floods

In 1665, painter Johannes Vermeer, the Sphinx of Delft, put the finishing touches on the luminous Girl with a Pearl Earring, a now-iconic image that depicts what art historians call a “tronie,” or a fictionalized person, lips slightly parted, wearing an exotic turban and a single oversized pearl. The mysterious work has beguiled audiences for centuries; it currently hangs in Room 15 at the Mauritshuis, the self-proclaimed “most beautiful museum in The Hague.” Though The Hague and the museum are protected by seawalls and dikes, storm surge barriers and floodgates, it is, like 26 percent of the Netherlands, still below sea level. Protecting their masterpieces from flooding is front of the mind for the Mauritshuis’s curators and conservators.

“Our most likely climate threat is flooding, due to extreme rainfall or western winds causing a tidal wave braking trough one of the coastal defenses,” says Judith Niessen, head of collection and research at the Mauritshuis. “Although this has not happened in the past, we do believe that we need to prepare for such scenarios.”

The museum has a “priority list” of objects that would be moved first, and Girl with a Pearl Earring, as well as other Northern European masterpieces held by the museum, including works by Rembrandt van Rijn and Peter Paul Rubens, are likely on the list. The in-case-of-disaster protocol for imminent flooding also includes “switching off electricity, building dams, closing extra security doors, but also training on what to do afterwards, [including] triage of the damage and putting dehumidifiers in place.”

Niessen notes that the safety measures are constantly changing, that there is “never a status quo” but can shift to react to all probable threats. Given the pregnable location of the museum, staff need to be continually watching, monitoring future threats and adapting as weather patterns and sea levels change.

Resilient architecture and institutional planning keep rare American pottery safe

Often, damage comes in a more dramatic form: hurricanes. According to a 2024 study from nonpartisan nonprofit Climate Central, the severity of hurricanes has been significantly “boosted” by ocean warming. Fortunately, the Charleston Museum in South Carolina protects their collection of significant works by enslaved potter David Drake behind what Curator of History Chad Stewart describes as “big, brown, and brick” Brutalist-style building.

Built in the 1980s, Stewart says, “aesthetically, our building does not get great views from the public.” He recalls a time when a curator came over from the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and said upon exiting the car, “My, what a lovely prison you have.” Yet the structure has performed well in major weather events like Hurricane Hugo which hit Charleston as a Category Four in 1989. For a major storm, like Hugo, Stewart says it’s museum policy to “mobilize our curatorial staff from all departments and box up the contents” of their nearby, affiliated historic houses, moving their extended collection to the relative safety of the main museum.

The museum's significant collection of Drake pottery stays safe behind the solid brick-and-steel facade. The Charleston Museum owns the largest collection of Drake’s work in public hands, and these stoneware pots and jars are considered a highlight of the notable collection. “What makes the Drake pottery so valuable culturally is his story,” says Stewart. Drake learned his trade as an enslaved person, and although literacy among slaves was legally forbidden at the time, he learned to read and write. Stewart argues that the Drake’s “agency” and “expression” combined to create works of remarkable importance. Many of Drake’s elegant, hand-thrown jars and jugs are decorated with lines of verse written by their maker. “Dave belongs to Mr. Miles, where the oven bakes and the pot biles,” reads one jar, dated July 31, 1840. “It stands out to me because referencing his own enslavement was a rare and powerful thing,” Stewart says.

“Our building was designed with hurricanes in mind,” Stewart adds. “Our David Drake pottery is stored in an area that is as protected as we can make it.”

Conservators at a historic Miami mansion work to protect it from rising sea levels

Rising sea levels are a concern at Vizcaya Museum and Gardens in Miami, Florida. A National Historic Landmark, the 1916 mansion sits directly at sea level, a mere 100 feet from Biscayne Bay, which is especially vulnerable to rising sea levels. “We’re experiencing difficulties with storms, rainfall, pests, and of course, climate management,” says Vizcaya’s lead conservator Davina Kuh Jakobi. Not only do they have to contend with termites and shipworms, but they’re also slowly watching as the ocean creeps closer to the Renaissance-inspired garden and grounds.

“We are located in one of the most vulnerable areas in one of the most vulnerable cities in the world to climate change and sea level rising,” says horticulturalist Ian Simpkins. “We’ve been no stranger to disasters in the past. But the effects and the severity have ratcheted up.”

Simpkins has been at Vizcaya for over 18 years, and in that time, he has noticed a marked increase in the level of high tides, especially during the spring and fall. The Theater Garden, located on the eastern edge of the nearly 50-acre property, never used to flood; now it’s submerged under water each year, sometimes for months. The Marine Garden also routinely floods, and the rising water levels are threatening both the outdoor and indoor statuary. Several murals, located throughout the property, are under stress as salt water encroaches. “The stone on site is very soft and porous,” says Kuh Jakobi. “It deteriorates relatively quickly in relation to other limestones.”

To protect Vizcaya, FEMA has issued a grant that will be used to fund the construction of higher seawalls. To protect the gardens, Simpkins and his staff have been sourcing diverse plant material with a focus on species that can withstand flooding and high salt concentration in the soil. But, as sea levels continue to rise, there’s only so much that can be done to preserve this portal into the art and excesses of the late Gilded Age.

“We’re not slowing down, and there’s a real risk that in 50 or 80 years, you won’t be able to walk through the gardens because they’ll all be under water. The house will remain, but it will be an island,” says Simpkins.

Keepers of Britain’s most iconic clipper safeguard it from extreme heat

At the Royal Museums Greenwich in London, where the Cutty Sark, a 19th-century tea clipper and UNESCO World Heritage Site, sits on the bank of the River Thames, shipkeeping technician Maddie Phillips worries about extreme heat events. Since 1954, the ship, once the fastest in the sea, has been dry docked where more than 17 million visitors have walked the planks of its deck, and while flooding and overtourism are a perennial concern, it’s the exposure to the elements that concerns Phillips. The “lower half of the ship is encased in a glass structure, which creates different temperature conditions for the hull,” she explains. “Some planks are exposed on one end and in temperature-controlled environments on the other.”

This uneven exposure means that the wood swells in the cold and shrinks in the heat at different rates. It is important to keep the material of the vessel at a relatively even moisture level—a difficult task during summer’s hottest days.“Temperatures are higher than they have ever been, leading to much shrinkage, with prolonged dry spells often followed by very sudden and heavy bouts of rain, which leads to much higher levels of water ingress than previously, causing its own problem in the fabric of the ship,” she says. The shipkeepers work daily to wet the planks of the Cutty Sark in an attempt to combat the shrink-swell cycle and preserve the centuries-old wood.

While the core focus of their work involves protecting the existing material of the Cutty Sark, the replacement of some material is inevitable. As often as possible, the ship’s keepers use reclaimed wood and traditional shipbuilding techniques to repair the walls of the vessel. “They often represent the most environmentally sustainable means of conserving the ship,” she says. “There can be difficulties with this, as some materials, such as teak and hemp rope, are difficult to source.”

Fighting fire at Frank Lloyd Wright’s iconic home

Each spring, the grounds of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin West bloom bright with color. The 1937 house lights up with scarlet and yellow cactus blooms, creating a picturesque backdrop for Wright’s winter retreat. The graceful low-slung building is an important part of the United States’s architectural history, yet the entire compound is in near constant danger of burning to the ground. “By the time summer comes around, all that beauty turns into timber,” says Fred Prozzillo, VP of preservation and collections at the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, which is headquartered at the site. “Fire is always a worry for us.”

Every year, the staff at Taliesin West meets with the Scottsdale Fire Department to teach firefighters about the on-site collection and how to best protect it while educating the museum staff about fire prevention techniques, like brush clearing and buffer zones. While Prozzillo feels that “all of the collection is important,” he also recognizes that certain buildings have priority, specifically Lloyd’s living spaces. “It has the most collection items, so this is the one we want to hit first,” he says, noting Wright’s collections of Asian art and Native American pots.

It’s not just about the objects, but how each piece in the collection speaks to the others, creating a holistic picture of one man’s radical sensibility. The open floor plan of was revolutionary at the time, as was Wright’s site-responsive design. “He was breaking apart the Victorian standards and giving us architecture that would be more representative of our free democracy,” Prozzillo explains. “It blends with the landscape. It’s an amazing place, it really is.” Unlike the Getty Villa, Wright didn’t build his masterpiece with vulnerabilities in mind. A fire like the Palisades wouldn’t skip over these structures; it would consume them.

That kind of loss would be immeasurable: “Wright influenced how we build and live today, Prozzillo says. “If we lose that, we lose part of our history, and we have to be vigilant about it.”

The danger of losing the oldest figurative paintings in the world

Inside a limestone cave, tucked in a secluded Indonesian valley, there hides a warty boar. The stout, solemn figure is one of many earth-pigment paintings made by prehistoric hands that adorn the walls of Maros-Pangkep, located just an hour north of Makassar City. This distinctive landscape is defined as a karst region, a place where water has carved through the limestone, dissolving the bedrock, creating sinkholes, underground steams, networks of caverns, and (most dramatically) tall, tower-like hills. The Maros-Pangkep karst isn’t the only of its kind but is special because of what they house: paintings that date back 51,200 years, making them the oldest figurative paintings ever discovered.

Like the famous caves at Lascaux (which are a paltry 17,000 years old in comparison) the images offer a glimpse into the minds of our distant ancestors: an oversized wild pig with his snout partially open, surrounded by three human-like figures in various positions, all painted in red ochre. Experts believe that these caves challenge the once-held notion that human ingenuity and creativity began in Europe, rewriting the narrative around our leap into imaginative thought.

“It is only in the past decade that scientific analyses demonstrated the rock art of Indonesia is more than forty thousand [years old], and we now have evidence for more than fifty-thousand years old,” explains archeological scientist Jillian Huntley of the Griffith Centre for Social and Cultural Research in Australia.

In 2023, Huntley and her colleagues at Griffith University published a study of the Maros-Pangkep caves, which found that the paintings were being visibly damaged by salt weathering, a physical process of stone disintegration that has been exacerbated by extreme heat caused by climate change. The salts are deposited onto the walls of the cave through water, which then evaporates, leaving behind tiny crystals. As the temperature and humidity fluctuate, these crystals begin to shrink and swell, creating stress in the surrounding rock. When saltwater collects on cave art, it can create a pitted texture as the limestone crumbles to powder, or it can lead to flaking, “literally pushing the ancient surfaces of the cave off the walls,” Huntley explains.

Once the damage has been done, it can’t be reversed. “We are in danger of losing vital evidence of something deeply connected to what it means for us to be human,” Huntley says. She adds that the only way we can begin to mitigate the damage done to Maros-Pangkep is through immediate, global-scale action. And we haven’t finished documenting the vast network of art found in Maros-Pangkep. “We have yet to understand this part of our shared human history,” Huntley says.

The slow disappearance of an ancient city of Petra

The red rocks of Petra, Jordan’s most visited tourist site, are crumbling. The ancient, rock-cut Nabatean city, built in the fourth century BCE, continued to flourish after the Romans invaded (and conquered) in 106 CE. While some eclectic elements have been preserved perfectly underground, giving archeologists a good idea of how Petra once appeared, most of the site has degraded greatly over time.

“These guys were making razor-edged sharp flowers,” says University of Arkansas geosciences professor Tom Paradise, referring to the organic designs that can be found on facades throughout the city. “None of that is visible now in Petra. The disintegration makes everything look rounded and soft.” The analogy he offers is one of a “fancy cake, one with all the frosting and rosettes, in the rain.”

The greatest threat to the site is its visitors. Paradise has been studying the city for over three decades, and he says that the Roman theater at Petra has worn down more during the last 30 years than it has in previous centuries. “Because of shoes,” he says, “these shoes grip and grind faster.” The textured, curved rubber soles are designed to keep hikers surefooted also wear down rock quicker than traditional leather-bottomed sandals.

If it’s not the shoes, then it’s the air, specifically the air tourists breathe in and on Petra itself. The environment surrounding Petra is becoming more arid, which is normally good news for rock art, but not when there are hundreds of bodies moving through the interior spaces. “We’ve seen the humidity change 50 percent in the tomb, from tourists,” says Paradise. While it is normal for the humidity of the air to fluctuate, the rate at which its changing has resulted in increased stone breakdown or “rock rot.”

“It scares me that our vast architectural heritage—Petra, Leshan, Angkor, Taj Mahal—are ‘rotting’ faster than we could anticipate,” Paradise says, referring to major landmarks in China, Cambodia, and India. “It’s unique architecture that doesn’t exist anywhere else on earth,” says Paradise. “There’s nothing to be done.”

(The world's historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?)

Invasive pests could be a disaster for an Olmsted-designed park

According to Rodney Eason, director of horticulture and landscape at the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University, city parks and gardens all over America are feeling the strain of climate change. Part of Boston, Massachusetts’s famous Emerald Necklace, a system of parks designed by American landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted in the late 19th century to ring the city with greenery, the Arboretum serves as both a “tree museum,” showcasing thousands of species of woody plants, and a free, 281-acre recreation site. But the plants that have thrived at the Arnold Arboretum for centuries are under increasing stress, says Eason, primarily from the ever-hotter summers and the still-frigid winters. “Summers are hotter, but winters are as cold, if not colder than they were in previous decades,” he says. “Then, you introduce new pests and diseases […].”

It's a recipe for arboreal disaster. For the past decade, the trees have been suffering from a combination of drought, severe cold, beech bark disease, and they’ve recently suffered from beech leaf disease, which can kill trees. “It is a nematode that somehow got into the United States from Asia,” Eason explains. The Arnold staff is still figuring out how most effectively to treat it. While they’re always expanding, monitoring, and safeguarding their collection, there’s simply no replacing a 200-year-old tree.

Eason argues that losing the Emerald Necklace would render us “like Wall-E,” referring to the Pixar movie set in a distant future where the last remaining humans have been forced to abandon an uninhabitable planet earth. As humans, he says, “we need green spaces. Fredrick Law Olmsted […] knew that.”