A ‘Life From Scratch’ Offers a Seat at the World’s Dinner Table

When award-winning food writer Sasha Martin started the popular Global Table Adventure blog, she had a simple plan: chronicle her quest to prepare a meal from every country in the world for her picky-eater husband and new baby girl—all from their small kitchen in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

(How Easy-Bake Ovens Taught Us to Cook)

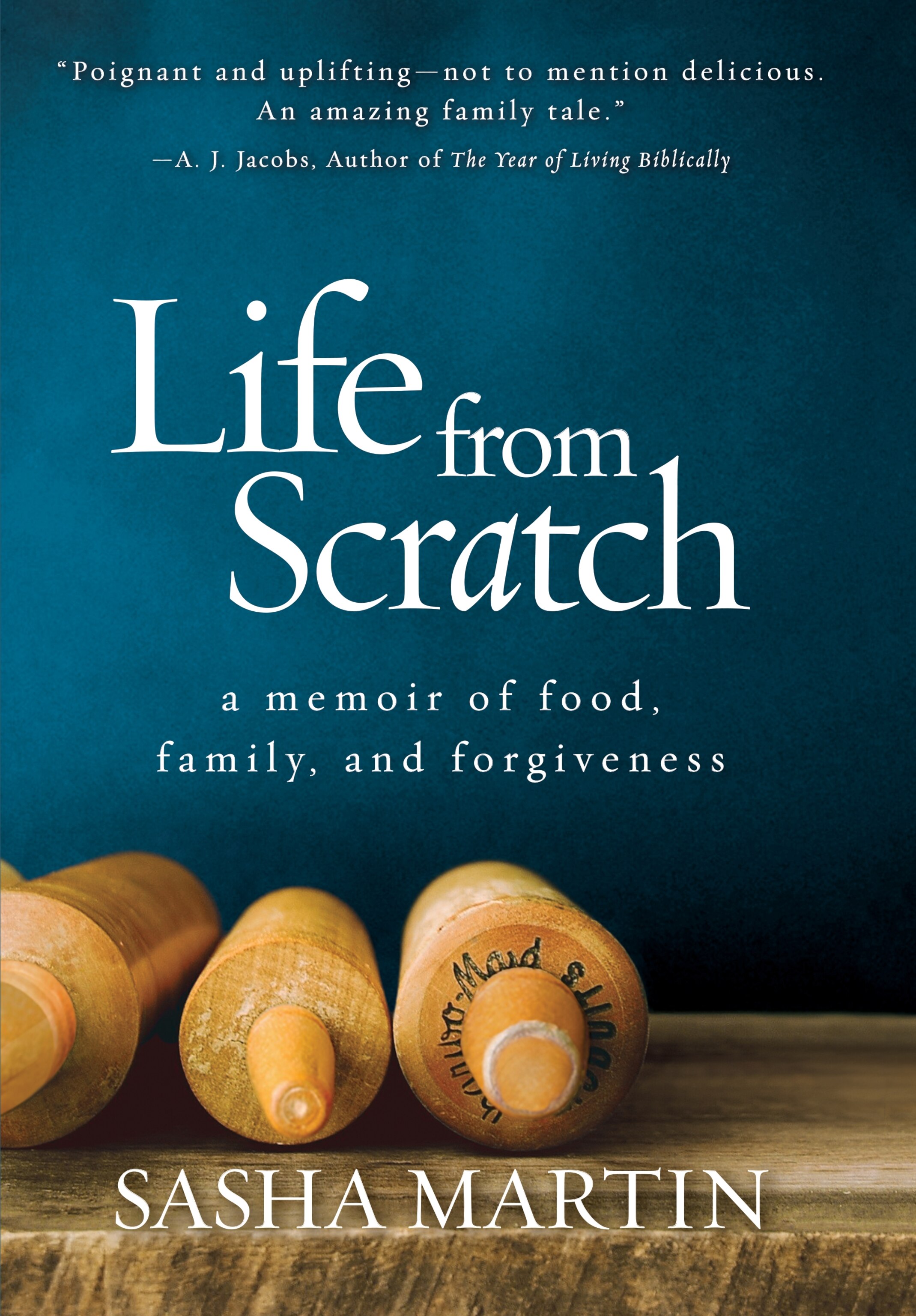

After her editor encouraged her to go deeper, this straightforward project ultimately turned into a quest to make peace with her own troubled past and introduce her young daughter to her global neighbors through food. Martin documents her search—and shares 29 recipes—in her new memoir, Life From Scratch, published by National Geographic. Our interview has been edited for clarity.

Leslie Trew Magraw: Much of Life From Scratch is about being separated from your mother when you were 10 and trying to reconnect with her as a young woman after spending years apart.

I never really had that unconditional home. Certainly love was there, in different forms, but the idea of a place I could call home wasn’t very clear for me. So, as I’m looking at my new baby, I think “cooking the world” was a way for me to work through some of those issues and look to the world for inspiration on a lot of levels.

I think a lot of people travel for the exact same reasons you’re describing. And because you weren’t able to, this was your way to travel without leaving home. This was your walkabout.

That’s right. I think that’s key. There are so many people who watch the National Geographic Channel and read the magazines, and I count myself as one of them, who daydream of the possibilities. But I think what was exciting for my readers and myself was the discovery that you really can go on adventures without leaving home.

Food is the one thing that if you have the right spices and buy the right ingredients, you can literally create the flavor of another place. It’s more immediate than armchair travel. I call it stovetop travel.

Stovetop travel! I like that.

I think the idea that exploration is for everyone is really important to what I do.

What’s your relationship with your mom now?

Our relationship is constantly evolving. We’ve done a lot of work to heal, and a lot of that was done through cooking. That was the language that she taught me as a youngster.

Even though she was a single mother on welfare, she used the kitchen and food as a way to let me see beyond our circumstances—that something else was possible or out there. That we weren’t limited.

So, we made things like German tree cake (baumkuchen), which is [composed of] 21 crepe-like layers that are boiled. It takes two days to make. That was kind of [my mom’s] style. It was a bit extravagant, but the message that it gave was really great.

What did you hope to teach your daughter by cooking the world?

I wanted her to feel as though she had a place in the world where she belonged. And that was, of course, because of my deep issues. But I also felt it was critical for children to grow up knowing their global neighbors.

I call them neighbors very purposefully because the world is so small now. I remember going on Facebook in its early days, when memes were starting to come out, and noticing that there were people commenting on the memes from different parts of the world, even arguing with each other.

This meme, this silly picture with a [phrase] on it, is a place where people are coming from all over the world to comment. And I feel like if there’s not already a foundation for young people when they’re in that environment to respect and understand each other…I’m getting off track.

Food is a great way to create that common ground.

Yes. My philosophy with international food has evolved [over time]. In the beginning I was making tougher, more exotic recipes. But as time went on, I found myself driven to make meals that were more approachable, friendly for a weeknight. And I wanted to share recipes that were bridges to other cultures [through my blog].

A lot of celebrities that do international food tend to choose the most shocking recipes. I get that; I think there’s interest in that. But I also think that if you don’t have that bridge first, people immediately [put up] a wall in their mind about that culture. “Gross! Those people eat such weird things.”

There does seem to be an exoticization of people through food these days. You see that all the time on cooking shows that emphasize difference, not commonality.

Right! For example, I have a recipe for Mongolian carrot salad and a recipe for Moroccan carrot salad. The recipes aren’t super complicated, they just [involve slightly] different ingredients.

We all eat carrots. I think recipes like that are really fun ways for people to get interested in international cooking. And then they can go to the deep-fried tarantulas afterwards if they want.

Take the potato. There are a million ways around the world that people make potatoes. How nice, as a mother who has to feed a child and a husband, to have some variations on potatoes, or rice, right?

You grew up in Boston, moved to Europe to live with family friends when you were separated from your mother, then returned to the United States to attend college in Connecticut and pursue a scholarship at the Culinary Institute of America. At this point, you’ve been living in Tulsa with your husband for a decade. What was the biggest misconception you had about Oklahoma before you moved there?

That there really wasn’t…I didn’t think I was going to get any…Let’s see, what’s the right way to say this.

Culture?

A little bit of that, but [it was] more that I was [going to be] so remote from everything. They do call it the Flyover Zone.

What’s really funny is that when I started the blog and began cooking all these countries, I thought I was looking outside, to the world, to [make up for the fact that I was] living in this state where I didn’t have international opportunities. But when I started cooking the world, I started seeing the culture all around me. Kind of like learning a new word [and then seeing it everywhere].

Very early on, when I was cooking Algeria, a friend told me, “Well, hey, there’s an African market just down the road from you.” Literally, a mile and a half away from the house. I was able to get fermented locust beans, which taste kind of like blue cheese. They had all kinds of stuff. Huge yams, red palm oil.

That kind of thing happens often when you travel, those serendipitous how-did-that-happen moments. It’s like you brought travel to you by opening yourself up to this way of life. You invited the world to come to you. And it does, when you’re open to it.

It’s so crazy. Yeah! I am so glad that you get that.

How did you find your recipes?

That was something I got better and better at.

In the beginning, I did a lot of library research. Some countries were really easy to find information on, and others, of course, were really, really tough.

[Then I found] this great series, a five-volume set called The World Cookbook for Students, [which includes] recipes but also culinary introductions to every country in the world. So that gave me a good starting point.

Did your strategy change as time went on?

Once a year went by, I got more confident. And I would say that confidence came from cooking several countries in [a given region], so that I [better] understood the differences between, for instance, West Africa and East Africa. Over time, I got a sense of whether or not something sounded right, what might grow in different parts of the world.

I didn’t want to just use one source, so I looked for locals or someone who was in a country through the Peace Corps or as an ex-pat that I could email with.

Once, I found this orange-and-coconut bundt cake from Micronesia and thought “Wow, that sounds really good, but it sounds almost American.” There’s almost no information to be found, right? So I [searched out] a restaurant in the islands and used their contact form to ask if this was a traditional thing people would eat in the cities. And a woman wrote back and said, “Yeah, absolutely!” So I was really happy.

Do you come back to any recipes again and again that you made during your year cooking the world?

There are so many. One of my favorites is this acorn squash salad, which I made when I cooked Argentina. It’s based on a recipe from Francis Mallmann, an Argentine chef famed for his gaucho-style cooking.

It was common for gauchos (herdsmen of the South American pampas) to take a pumpkin or some kind of squash and roast it in the embers of their campfire, and Mallmann makes this amazing salad with it.

First, roast an acorn squash, cut in halves and seasoned with oil, salt, and pepper, until it’s really soft. Even though acorn squash is mild, roasting brings out its natural sweetness. After that, add peppery arugula, aged goat cheese, and Mallmann’s mint-oregano dressing.

When you mash it all together, the hot acorn squash melts the cheese and wilts the arugula. I love it.

It’s so ridiculously easy that I make it all the time. It’s also quite pretty.

Did cooking the world change how you view foods that once seemed familiar?

Yes, definitely. It’s made me less rigid in terms of how to use ingredients. Depending on where you are in the world, there are totally different applications. Now I know cinnamon’s not just for dessert and apple pie, it’s for rice, and that avocados have a life beyond guacamole.

In Cabo Verde, they use avocados mashed with chopped dates, a little sugar, and a capful of brandy. It’s sweet, a totally different way to enjoy it.

What’s your diet like these days, now that you’ve cooked every country in the world?

We still cook international food, but the pace is totally relaxed now. My daughter still says, “Mama, what country are we eating?“ She wants to know where the food came from, even if it’s just pasta or rice. It opens up our dinner conversation and allows us to bring in our global neighbors.

Leslie Trew Magraw is editor/producer for the Intelligent Travel blog network at National Geographic. Connect with her on Twitter and Instagram @leslietrew.