Dates: The Sticky History of a Sweet Fruit

When Nawal Nasrallah was growing up in Iraq, the last three days of Ramadan were consumed with a singular activity: stuffing dates into rich buttery cookies called ma’amoul.

“We used to gorge ourselves on those cookies,” says Nasrallah, author of the Iraqi cookbook Delights from the Garden of Eden and a small volume on dates. She now lives in Salem, N.H. “I cannot think of Ramadan without dates and at the end having those delicious date cookies.”

Nasrallah is not alone. Dates are key to Ramadan, an annual month-long period of spiritual reflection that began this week. During Ramadan, Muslims fast from dawn to sunset, taking neither food nor water. A date traditionally is the first food to pass one’s lips after the sun goes down. Dates also feature prominently in Eid al-Fitr, the feast that ends Ramadan, when they find their way into items such as Nasrallah’s ma’amoul.

To help American Muslims prepare, date growers in the Southwest’s Bard Valley have shipped more than 500,000 pounds of plump, glossy tree candy over the last couple of weeks to places such as Detroit, Houston and other cities with large Muslim populations. The annual Ramadan spike is second only to the one that happens at Christmas, says David Anderson, marketing director for Bard Valley Medjool Date Growers Association.

“We are knee-deep in filling orders for retailers,” says Anderson, noting that overall production also is up.

The American date industry traces its roots to the Middle East. Agricultural experts estimate that there are more than 3,000 varieties of dates, but U.S. growers primarily produce two: the deglet noor, a smallish, drier date often found in baked goods, and the medjool, a fat, maple-hued fruit prized for its succulent taste and texture. These are the dates piled in bowls and baskets during the holidays.

Both varieties were brought to the United States in the early 20th century by Walter Swingle, an “agricultural explorer” tasked by the U.S. government with searching the globe for exotic crops. Swingle began bringing dates to the United States as early as 1900, says California historian Sarah Seekatz, mostly the deglet noor. In 1927, Seekatz says, Swingle convinced a local Moroccan leader to part with several medjool offshoots that were sent to the United States.

Every medjool date grown in the United States can trace its roots to that single oasis in Morocco, Seekatz says. In the Bard Valley, each of the 250,000 trees descends from the “Big Six,” six trees grown from offshoots of Swingle’s original cache.

Today, American growers produce about 33,000 tons of dates per year, according to government figures, a pittance compared to the more than 6 million tons put out by Middle Eastern countries, but it’s a growing industry. American dates come almost exclusively from Bard Valley and from California’s Coachella Valley, a slim slice of desert that stretches south of Palm Springs.

Selling a ‘Culture’ Along With a Fruit

Up until the last century, Americans did not think too highly of dates. So what caused them to change their minds? Marketing, baby.

For date growers in the early 20th century, the connection with the Middle East was too much to resist. The country was in love with “the Orient” then, swooning over One Thousand and One Arabian Nights and Rudolph Valentino’s 1921 silent film The Sheik. Farmers, governments, railroads and others poised to make money around the industry saw an opportunity, Seekatz says. They transformed the Coachella Valley into a confection of pyramids and camels and harems that would draw people to the place and to the product.

“It’s an imagination, it’s not the actual Middle East they’re embracing,” Seekatz says. “It reinforced the stereotypes.”

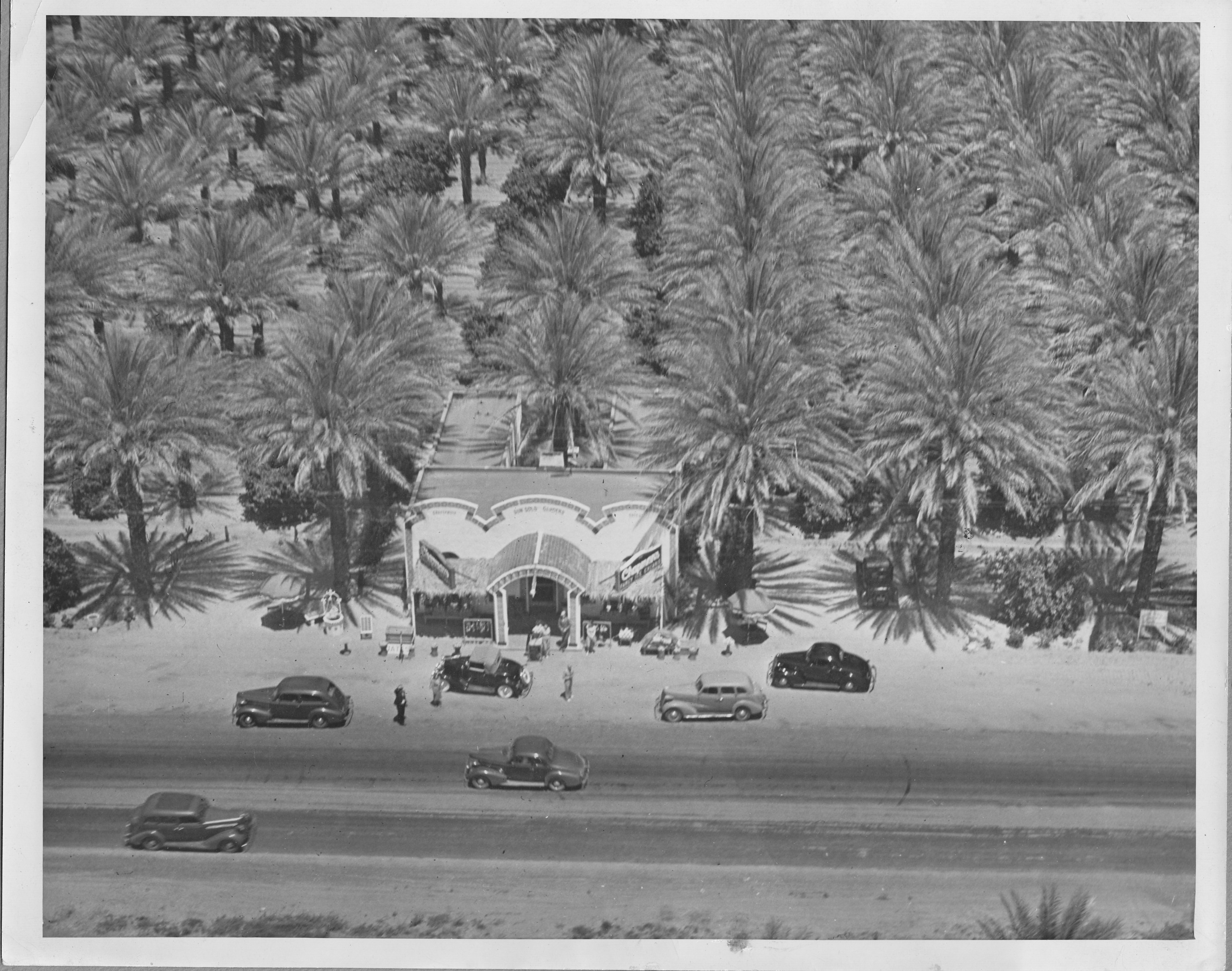

Towns named “Mecca,” “Oasis,” “Arabia,” and “Thermal” unspooled along the valley floor, Seekatz says. Streets were given names such as “Luxor,” “Baghdad,” and “Cairo.” “Date gardens”—roadside attractions often featuring palm trees, Arabian-themed architecture, “authentic” Bedouin tents and, of course, dates—dotted the highway. In the 1920s, Seekatz says, plans were drawn for an Arabian-themed resort to be called “The Walled Oasis of Biskra,” after the Algerian city Biskra.

“It was going to be like a Chinatown, where tourists would come and imagine they were in North Africa,” she says. “And because there was no population of North Africans or Middle Easterners they had Native Americans stand in. And they put on costumes and led camels from the train station.”

Most of the project was derailed by the Depression. The Coachella Valley History Museum is now the keeper of much of the historic photos and kitsch from that time.

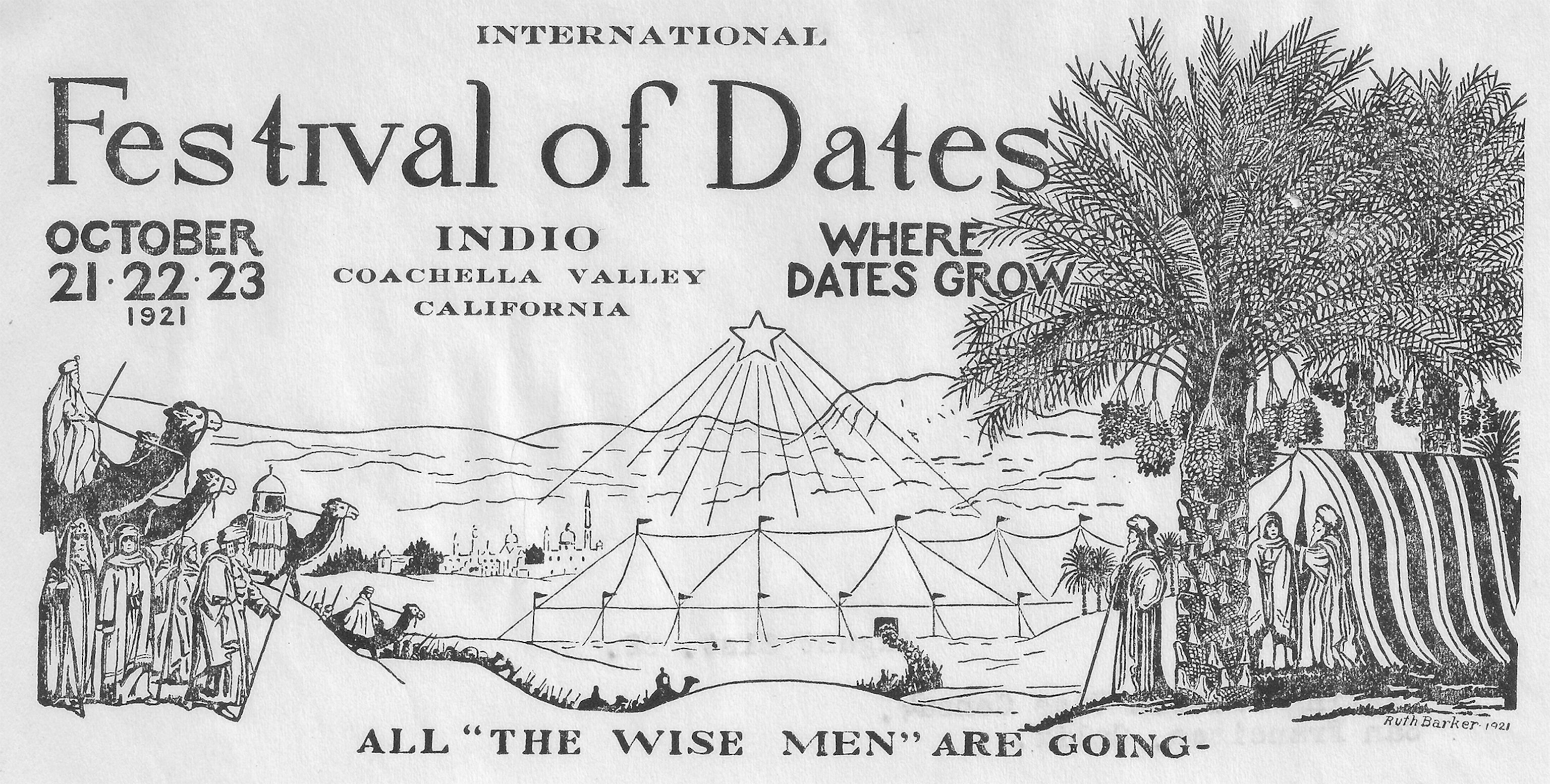

But perhaps the crowning effort of the industry was the annual date festival. Launched in 1921 in the town of Indio, the festival featured Middle East-inspired sets, camel and ostrich races, an Arabian Nights pageant, and a contest to crown a Queen Scheherazade. In the years after World War II, Seekatz says the whole community would dress up for the tourists—your waitress might be in billowing pants and a genie cap; your ticket taker at the Aladdin Theater might sport a fez. Few people dress up these days, Seekatz says, but the pageant continues—with some changes.

“It’s a musical now,” Seekatz says. “They re-word modern hits. Instead of ‘All the Single Ladies,’ it’s ‘All the Persian Ladies.’”

Moving Into Modern Times

It’s not the 1920s anymore, and Americans are less tolerant of stereotypes and potentially insulting cultural depictions. In cooperation with Arab-American leaders, Coachella Valley High School—long known as “the Arabs”—recently changed its team name to the “Mighty Arabs” and its Arab mascot from a brutal looking caricature to a more elegant figure. And growers say there has always been a healthy—and real— exchange between American and Middle East growers.

For decades, scientists and growers on both sides have exchanged breakthroughs. Students have done home-stays with growers to learn about new technologies. And American growers have even sent offshoots back to the Middle East to help repopulate date orchards decimated by pests.

Today’s growers have abandoned the Middle East marketing theme, catering instead to health-conscious consumers. For the last few years, Anderson says, Bard Valley growers have spent more than a million dollars annually to create the “Nature’s Delight” brand name and to position dates as “nature’s power fruit.” The result? A doubling of U.S. sales over the last five years, he says.

Anderson credits the growing American Muslim population, retailers’ embrace of the market and an aggressive marketing campaign by growers. “All of those things are really helping our business domestically,” he says.

Michele Kayal is the co-founder of American Food Roots. Follow her on Twitter @hyphenatedchef.