Don’t let your babies grow up to be pirates.

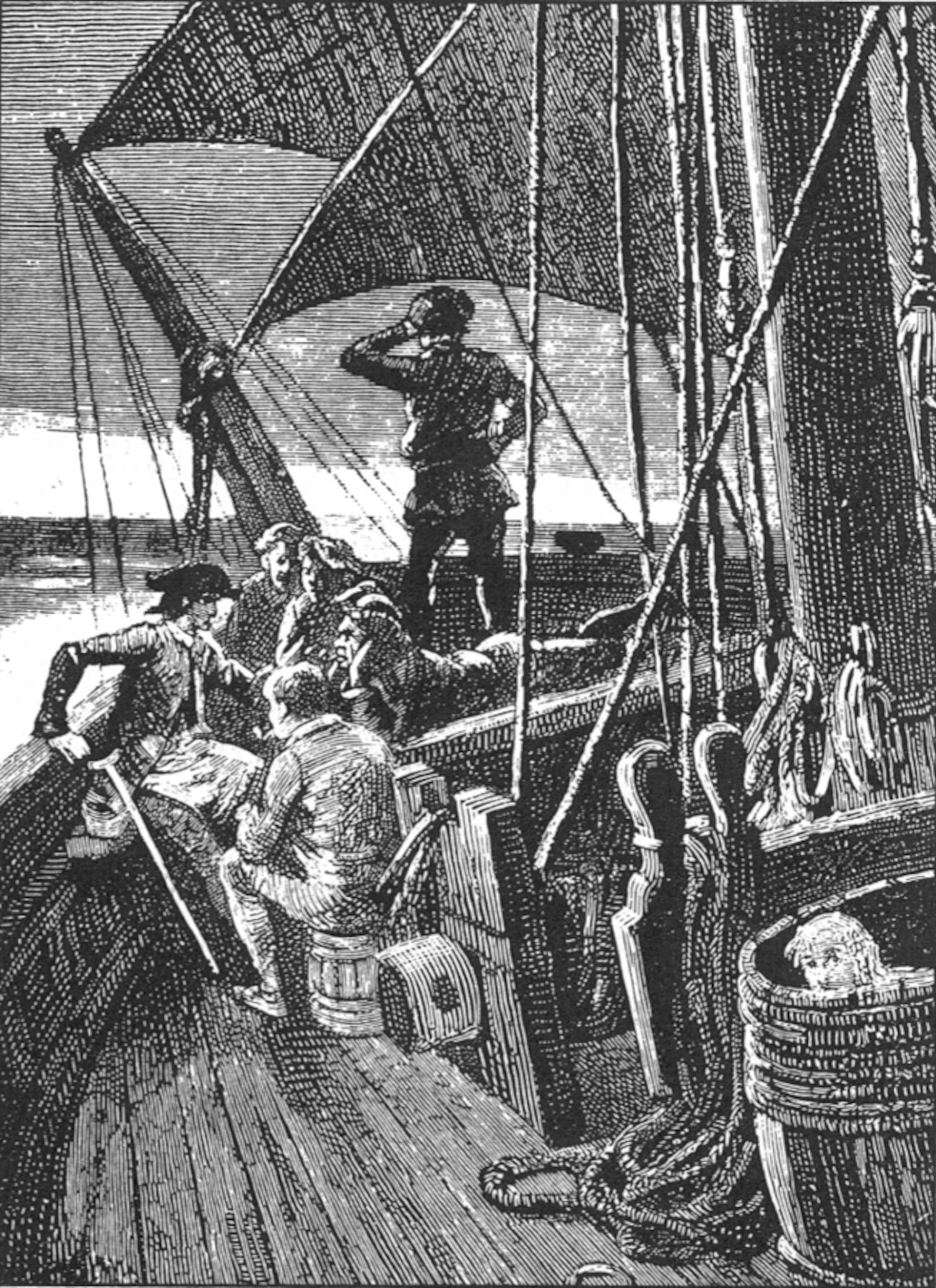

Historically, pirate life—forget gorgeous swashbuckling Johnny Depp in Pirates of the Caribbean—has been brutal, nasty, and short. Even in the so-called Golden Age of Pirates—a brief slice of time in the late 1600s and early 1700s when such piratical superstars as Blackbeard and Captain Kidd roamed the seas—most pirates lived in cramped miserable quarters and suffered from debilitating disease. The majority of them probably didn’t survive to see thirty and a good number of them ended their careers abruptly on the gallows. It’s a disappointingly unromantic, un-Jack-Sparrow-like picture. And on top of all that, pirates ate terrible food.

A recent study published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology, based on an analysis of nitrogen and carbon isotopes extracted from the bones of 80 18th-century British sailors, indicates that they ate just what the Royal Navy’s Victualling Board ordered as official rations: bread, beef, an occasional dollop of butter and cheese, and a gallon of beer a day. This was worse than it sounds. Shipboard food was necessarily limited to what would keep in the course of prolonged voyages. Bread was served up in the form of hardtack or ship’s biscuit, fearsomely durable squares of flour-and-water dough that—after a few weeks at sea—was inevitably infested with weevils. Beef was salted or dried, in which form it resembled black oak. Sailors often carved it into buttons and belt buckles.

Beer, ale, and rum were preferred for drinking since all kept better than fresh water, which spoiled and turned slimy in its storage casks. Pirates, by all accounts—perhaps to make up for the food—were mad for alcohol. A Captain Nathaniel Uring, who was shipwrecked in the Caribbean in the 1720s and spent four months with an enclave of pirates, described them as a “rude drunken crew.” (“Their chief delight is drinking…keeping at it sometimes a week together…”) Blackbeard claimed that strong drink was the only thing that kept his men from mutiny; and pirate Calico Jack Rackham was ultimately captured (at anchor) because he and his crew were too soused to either flee or put up a fight. Bartholomew Roberts—Black Bart—arguably the most successful pirate of the Golden Age, with 470 captured ships under his belt—was distinguished by the much-remarked-upon fact that he only drank tea.

Occasionally pirate fare was far worse. Pirate Henry Morgan’s and crew—stranded in 1670—were reduced to eating leather satchels (shredded and fried). Female pirate Captain Charlotte de Berry’s crew, shipwrecked and in desperate straits, turned to cannibalism, eating two slaves and Charlotte’s husband.

Luckily, to balance out this dismal lot, there’s William Dampier (1651-1715). Described as “a pirate of exquisite mind,” Dampier, as well as a buccaneer, was a dedicated naturalist, prolific author, astute hydrographer, world traveler, and adventurous foodie. His pioneering studies of wind, ocean currents, and the natural world influenced—among others—James Cook, Horatio Nelson, Alexander von Humboldt, and Charles Darwin. He crossed the Isthmus of Panama on foot, circumnavigated the globe three times, and wrote a bestseller about it in 1697, A New Voyage Round the World, which spawned a European passion for travel books that was to last for decades.

He visited Australia over eighty years before Captain Cook landed there, and was the first to describe its flora and fauna. He rescued castaway Alexander Selkirk from his lonely island, thus inspiring Daniel Defoe to write Robinson Crusoe. He penned the first English description of the zebra.

And, above all, he ate.

Over a thousand entries in the Oxford English Dictionary are attributed to Dampier, many of them having to do with food. Dampier gave us such terms as barbecue, cashew, kumquat, soy sauce, tortilla, and breadfruit—his praise for this last so enthusiastic that it led the British to attempt to transplant it to the British West Indies. (Captain William Bligh, on board the Bounty in 1787, was transporting breadfruit seedlings from Tahiti when sidelined by Fletcher Christian’s famous mutiny.)

Dampier routinely paired biology with meals. He observed, carefully described—and then ate—flamingos (“the flesh is lean and black yet very good meat”), armadillos (“tastes much like land-turtle”), guavas (“bakes as well as a pear”), locusts (“very moist, their heads would crackle in one’s teeth”), sea lions, ostrich eggs, and Galapagos tortoises, the flesh of which he compared to chicken.

Portions of his journals read like cookbooks. He noted down methods for preparing plantains (good baked in everything from tarts to boiled pudding) and recorded what may be the first recipes in English for guacamole and mango chutney. “When the mango is young, they cut them in two pieces, and pickled them with salt and vinegar, in which they put some cloves of garlic. This is an excellent sauce, and much esteemed.”

In Tonkin (north Vietnam), he noted that the natives ate “great yellow frogs” and elephant; in Guam, he admired the coconuts; in Central America, he devoured prickly pears, even though they turned his urine so red that it looked “like blood.” “This I have often experienced,” he wrote insouciantly, “yet found no harm by it.”

By the 19th century, with the help of Lord Byron, Sir Walter Scott, and Robert Louis Stevenson—who, in 1883, published Treasure Island, the ultimate pirate book—pirates had taken on the romantic and largely imaginary personas that have since tempted generations of ten-year-olds to run away to sea. Wisely, there’s not much literary emphasis on food—though in Treasure Island, the Hispaniola seems to have been better supplied than most. There was an apple barrel on board and, Stevenson tells us, everybody got double grog on birthdays.

Still, to this day, no pirate real or imaginary has held a candle to the remarkable and multitalented William Dampier—who may just possibly have been the world’s only pirate with a passionate and perceptive interest in food.

Salmagundi

Other than hardtack and salt beef, the closest we may get to a genuine pirate dish today is salmagundi, loosely described as a “salad,” and consisting of a random hodge-podge of ingredients, generally a scrambled concoction of meat, fish, vegetables, and fruits.

Try this recipe from 1712:

Chop into small chunks turtle meat, chicken, pork, beef, ham, pigeon and fish. Marinate with spiced wine and roast. Add the meats to boiled chopped cabbage, anchovies, pickled herring, mango, hard-boiled eggs, palm-hearts, onions, olives and grapes. Add pickled chopped vegetables and garlic, chili pepper, mustard, salt and pepper, and serve in a mound upon a large dish.

This story is part of National Geographic’s special eight-month Future of Food series.

References

- Preston, Diana and Michael. A Pirate of Exquisite Mind. Explorer, Naturalist, and Buccaneer: The Life of William Dampier. Walker Publishing Company, 2004.

- Roberts, Patrick, et al. “The men of Nelson’s navy: A comparative stable isotope dietary study of late 18th century and early 19th century servicemen from Royal Naval Hospital burial grounds at Plymouth and Gosport, England.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology, May 2012, pp. 1-10.

- The text of William Dampier’s A New Voyage Round the World can be found at Project Gutenberg of Australia.