To save the planet, Edward Norton wants to do more than appeal to our better angels

In Kenya, the actor and longtime conservationist is championing pathbreaking ideas about ecotourism—and making sure profits remain in-country.

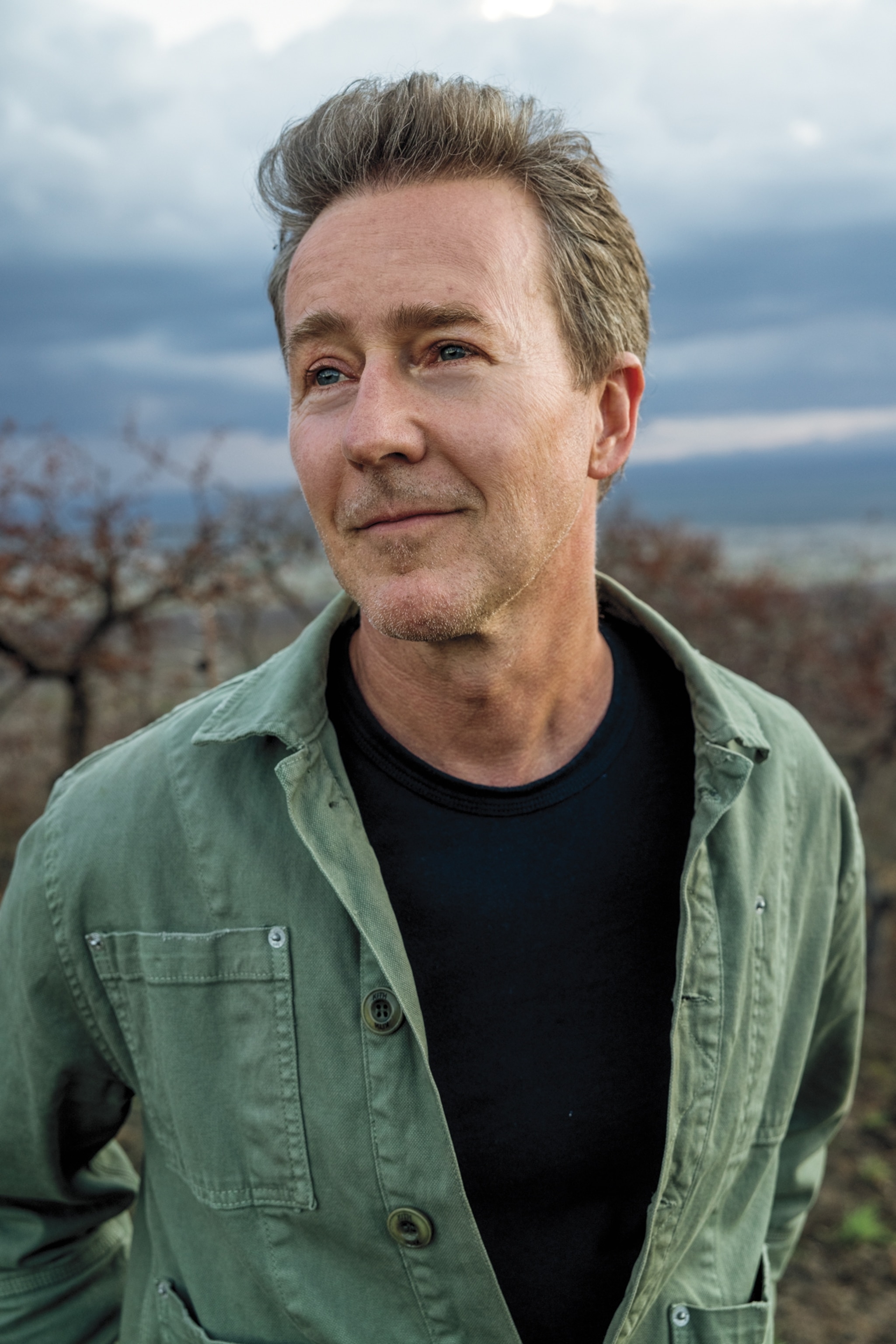

From an early age, Edward Norton was given an education in what protecting the environment really requires. His father, Edward M. Norton, an environmental litigator, founded the Grand Canyon Trust and co-founded the Rails to Trails Conservancy. Norton’s maternal grandfather, the real estate developer and urban planner James Rouse, was a pioneer in low-income housing policy. “I just grew up listening to people talking about social entrepreneurship, mission-driven strategy, and fundraising,” Norton, 55, explains. “Everyone around me was always on the stump, nobly trying to raise money. I certainly cannot remember a time my dad wasn’t raising money for environmental organizations.”

Norton built his own career in a different field, riding his work in films like American History X, Fight Club, and 25th Hour to a perch as one of his generation’s best regarded actors. Most recently, he played social justice legend Pete Seeger to Timothée Chalamet’s punchy young Bob Dylan in A Complete Unknown. When Norton first became famous, he concluded that he wasn’t interested in garden-variety celebrity ambassador work. “One thing I’ve always had a very, very sharp sense of is that I am not interested in accessorizing or being some weak sauce kind of articulator,” he says. “I’m not interested in what I would call the soft mission of being a public advocate. It’s not that I don’t believe those things are important, but that held no nourishment for me.”

What does nourish Norton, he says, is his work with a Kenya-based organization called the Maasai Wilderness Conservation Trust. Norton, who serves as president of the group’s U.S. board, describes it as “an economic development–first organization figuring out how to create preferential economics out of natural resources for communities,” which is another way of saying that the trust is dedicated to thinking creatively about ways to tie Maasai efforts of protecting their land and the wildlife there to economic development.

The group does plenty of the things you might expect from a Kenyan conservancy. “We run over 220 community rangers, wildlife enforcement, biodiversity monitoring, all of that stuff,” Norton says. But the trust, he explains, is a receptacle for bolder ideas too. One project he’s particularly proud of funnels revenue from the sale of carbon offsets to local Maasai communities who use that money to support health, education, and conservation initiatives.

The sizable concern that preoccupies Norton would be familiar to his father and grandfather: what he refers to as the “white-knuckle experience” of raising funds. This led Norton to a realization. “We can’t have the global conservation movement remain a donor-funded philanthropic strategy,” he says. “It just can’t. It not only can’t scale; it fundamentally is too unstable.”

A new model is needed, and Norton gets especially energized when discussing what he thinks it will be: a reimagining of the luxury ecotourism model to better support conservation efforts. The way Norton and his partners see it, tourist dollars being spent in fragile places ought to remain in-country—or better yet, in-community. Norton and his team have started a company called Conservation Equity that will invest in tourism in critical places—but, crucially, will reinvest its profits locally, rather than delivering returns to shareholders. Norton is bullish on the model’s prospects. “I think what we are doing has no precedent,” he says. “If we get it right, I would argue we’ll have contributed a big new idea about how conservation can be financed, and incentivized, and economically structured globally. I think we’re on the cusp of demonstrating how powerful tourism could actually be if the mission-driven world can come up with a model to compete against private equity capital.”

Norton thinks we’re at a pivotal moment where the mechanism of conservation can be reinvented. “We are in the era of the economics of nature. We’re forcing ourselves to accurately account for nature within our economic system,” he says. “It may not be as romantic as John Muir, but I think it’s got to be acknowledged that the needs of eight billion people are not going to take second-tier priority to the spiritual value of nature. They’re just not. If you cannot deliver a more resilient and superior economic outcome from stewardship and restorative stewardship of nature, you lose.” And Norton isn’t particularly interested in losing.