These Chinese immigrants opened the doors to the American West

As many as 20,000 Chinese workers were recruited to build North America’s railways. Their descendants are still fighting for recognition, writes photographer Philip Cheung.

After Utah State Historic Preservation Officer Chris Merritt showed me the ruins of Kelton, the last of the railroad ghost towns he wanted me to see that day, a storm whipped up on the horizon. I stood there watching the landscape, these clouds, the winds blowing up the dust, and I thought about what life was like more than 150 years ago for the Chinese workers who lived here then, laying rail and inhabiting this thrown-together desert settlement thousands of miles from home. There’s a fenced cemetery, not far away, where volunteers with dogs are helping locate remains outside the fence—probably the bones of Chinese workers, because the Chinese weren’t allowed to be buried where the white people were. I stood there too, and what I felt, for these people who worked so hard to help build America, was shame.

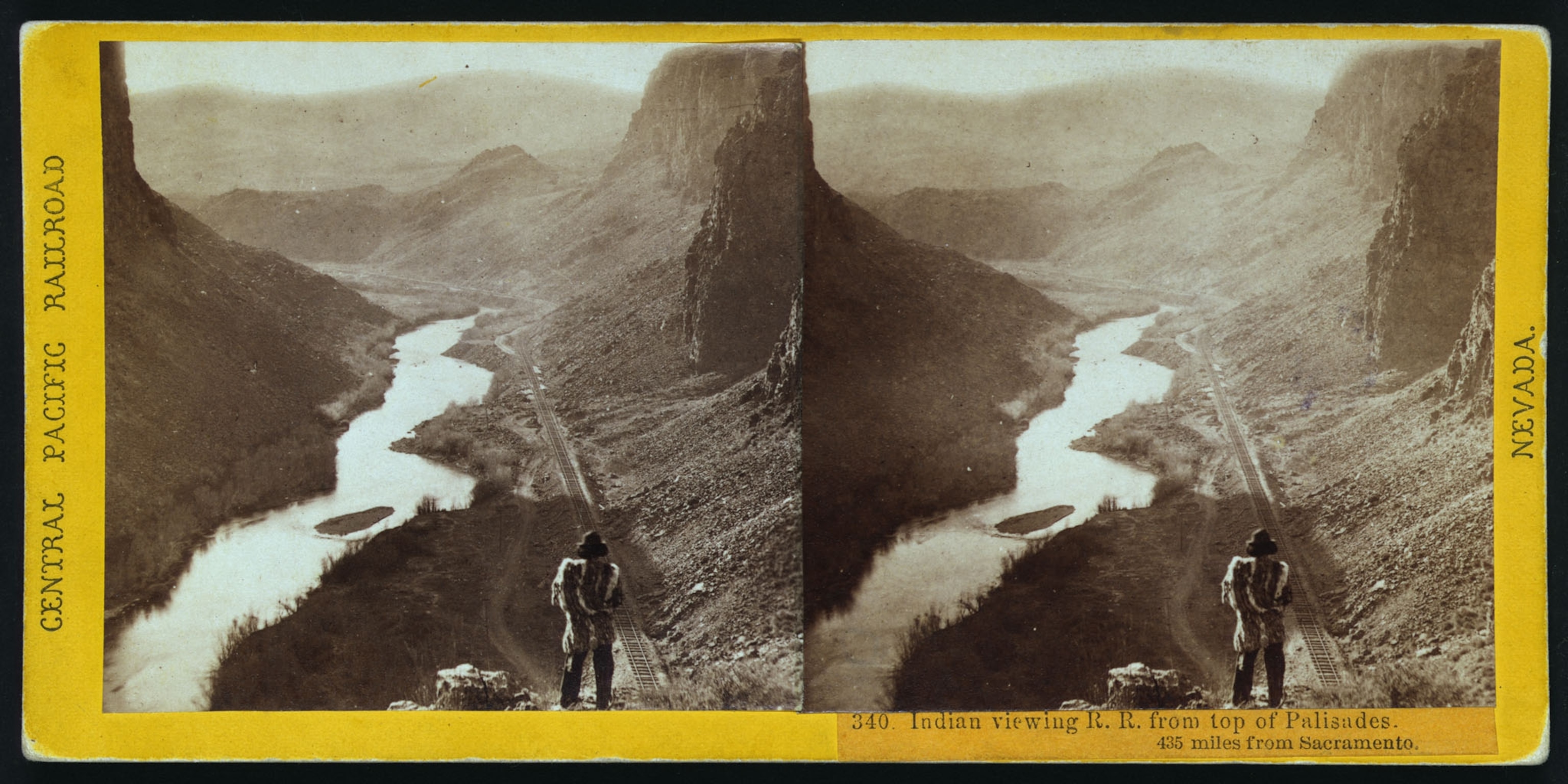

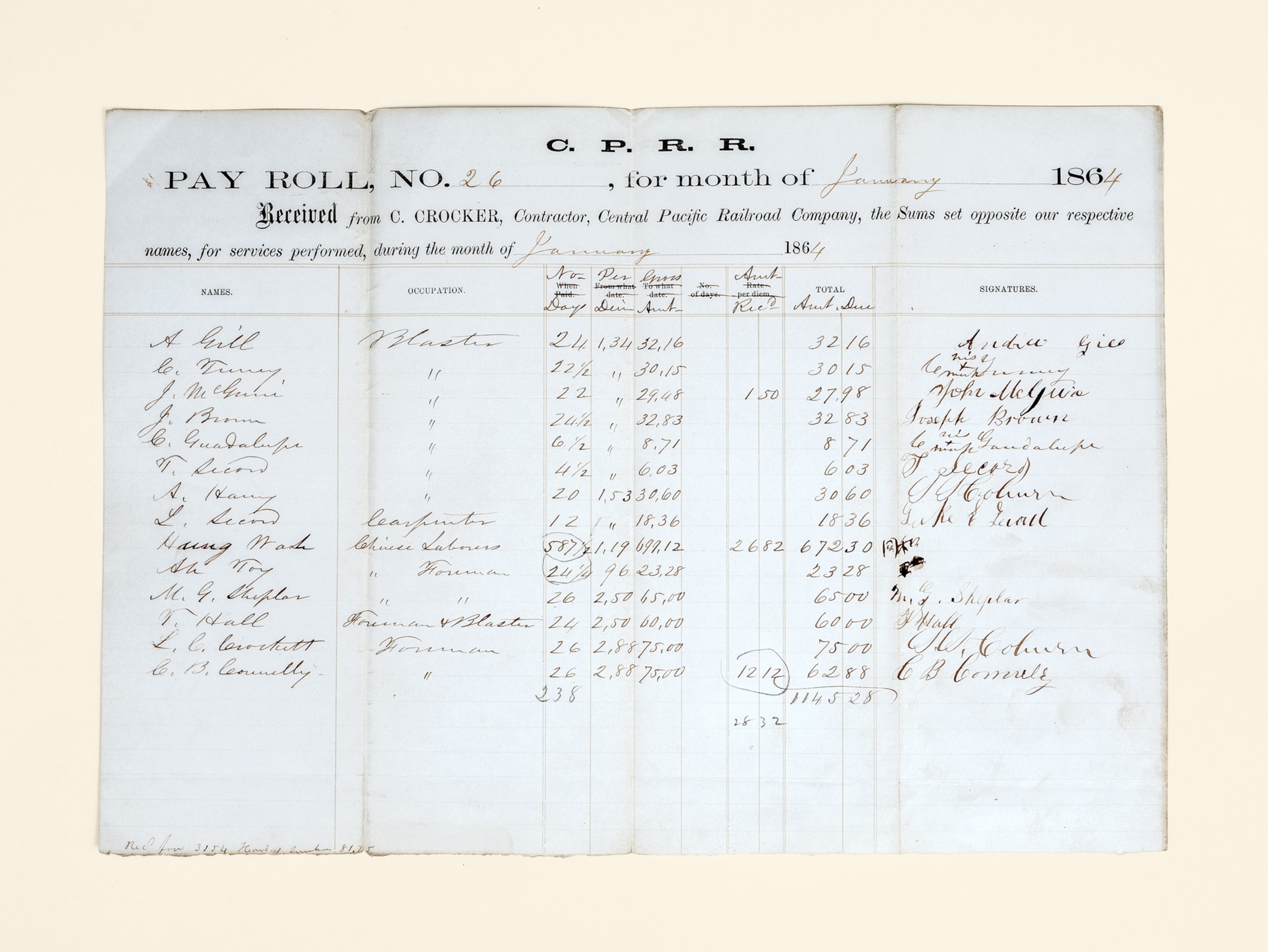

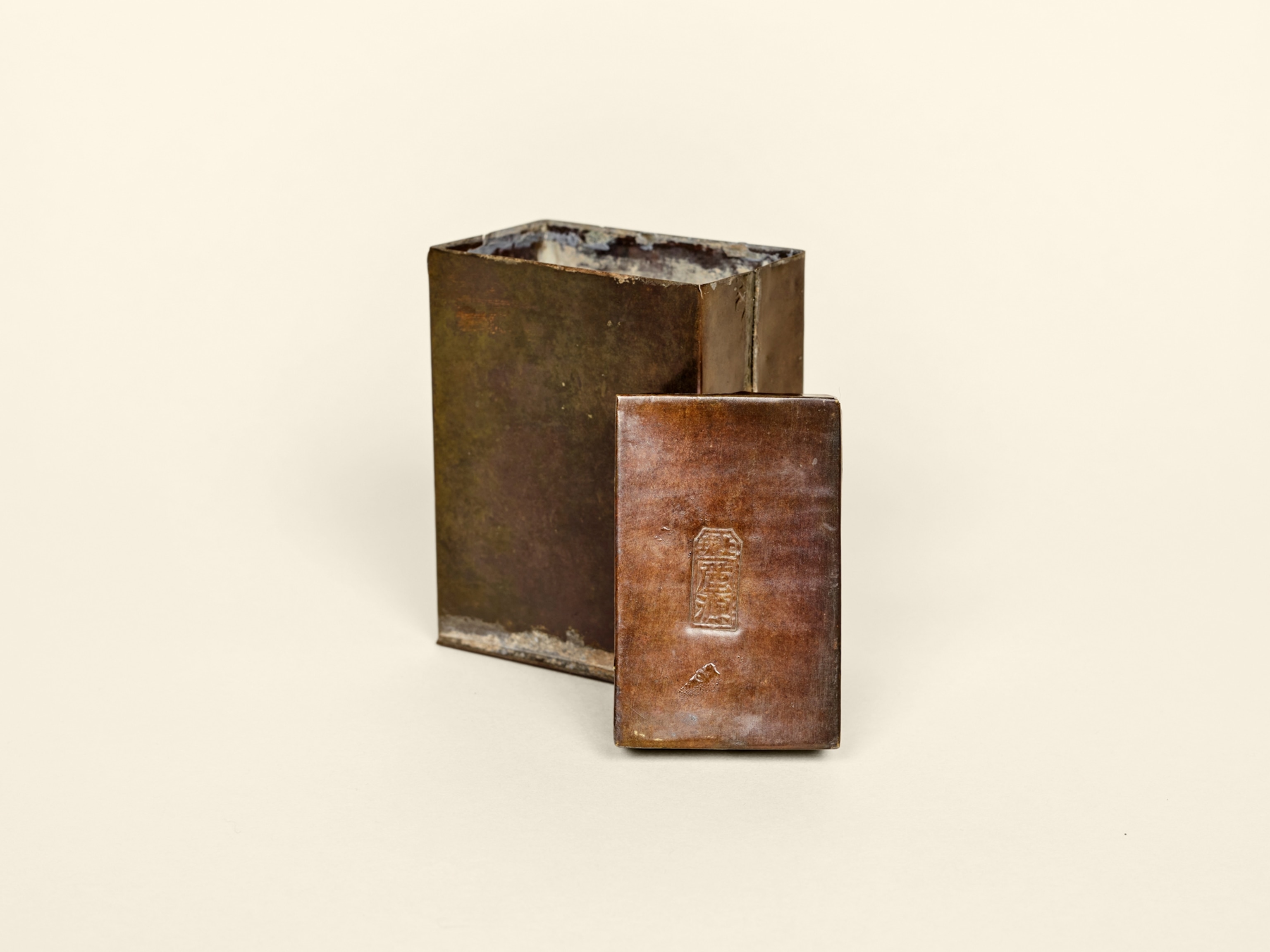

I grew up in Toronto, and when I first found out that Chinese workers had helped build the Canadian railways, I wanted to know more. The monumental story I learned is the heart of this photographic project: Before Canada’s construction ever got under way, immigrant laborers from China—10,000 to 20,000, according to the haphazard records—had built the hardest, most dangerous segments of the transcontinental railroad in the western United States. Through the Sierra Nevada mountains and across Utah’s high desert, it was mostly Chinese men who blasted tunnels and pounded track into place. The history of these immigrants who literally laid foundations for North American rail travel and the economic expansion of the American West is being told now by scholars, activists, and the workers’ own descendants, like Christopher Kumaradjaja, the great-great-grandson of the Central Pacific Railroad worker Hung Lai Woh. To this day, Kumaradjaja told me, people ask him where he’s “from.” He’s a fifth-generation American, he replies, and sometimes wants to add: Are you?

This story appears in the August 2023 issue of National Geographic magazine and is one of eight stories from The Past Is Present project, a collaboration between National Geographic and For Freedoms.

READ THIS NEXT

Faith fills more than a spiritual void for California’s migrant workers by Brian L. Frank

How Puerto Rico is grappling with its past—to reshape its future by Christopher Gregory Rivera

How has Texas changed in 20 years? She went home to find out by Tanya Habjouqa

Honoring the sacred places they were forced to leave behind by Dakota Mace

‘They emanate light’: Illuminating the lives of Mexico’s Indigenous people by Yael Martínez

These Black transgender activists are fighting to ‘simply be’ by Joshua Rashaad McFadden