Going Home, Home on the … Steppes of Eurasia

A great migration is underway in the world of cattle ranching. Cowboys from the United States, Canada, and Australia are taking cattle herds numbering in the thousands to start ranches on the Eurasian steppes. Why? Because the people of Russia and Kazakhstan have asked for their help solving a major food security problem

The collapse of the Soviet Union back in 1991 was hard on the people, but it was cataclysmic for cattle. When collective farming ground to a halt, many cattle farms were forced to liquidate their herds to pay off creditors, transactions that ended with a trip to slaughtering plants. Other farms disbanded their herds, dividing them equally among workers. If a cow was lucky, she lived out her milking career in a village garden plot before being butchered for chuck. Her offspring ended up on the village butcher’s block, filling a void left by Russia’s broken food supply chain.

Few farms kept up breeding programs to replenish their numbers. It created a downward spiral in the Soviet Union’s primary cattle-producing republics: Russia and Kazakhstan. By 2008, Russia’s national herd had plummeted from 52 million cattle to just 20 million. Kazakhstan’s herd shrunk from 10 million to 4 million head. The situation was so grave, these nations were spending a combined $4 billion importing red meat to feed their people. Cargo ships delivered beef from as far away as Australia and Brazil.

It was a strange scenario for two countries endowed with a cow’s paradise of water and grass. Unlike elsewhere in the world, cattle are native to the Eurasian and Kazakh steppes. Nomadic peoples domesticated cattle and horses there 10,000 years ago

kulaks

, or private property owners that were enemies of the people.Collectivization eradicated open-range cattle grazing and replaced it with industrial dairy farming—based on the idea that a dairy cow produces milk and meat. Which is true, if you don’t mind steaks stiff as boot leather and meatballs that crunch. Had the Soviet Union embraced Eurasia’s indigenous cattle culture, maybe Russia and Kazakhstan wouldn’t be in their current predicament.

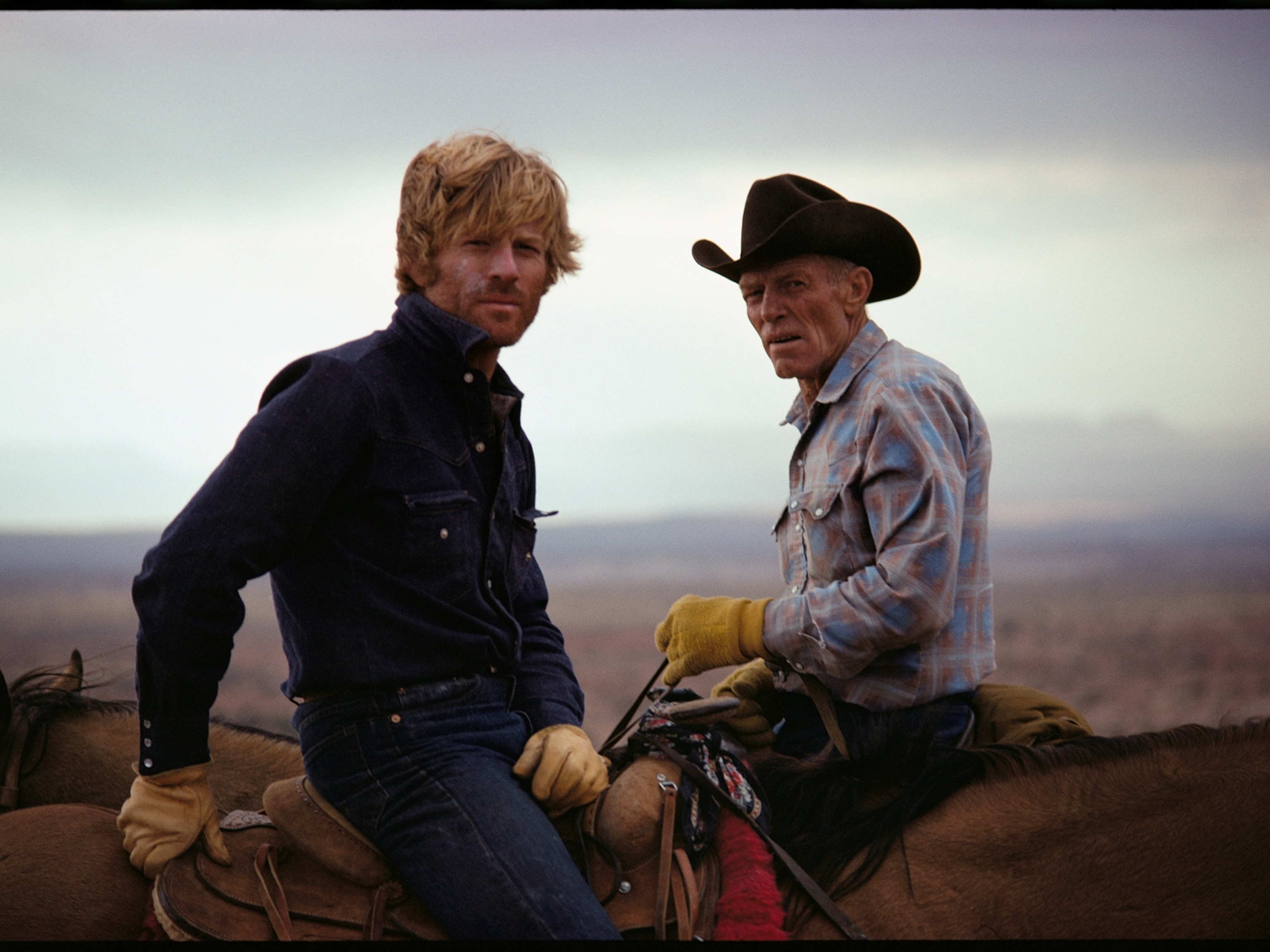

Today, wherever in the world cowboys ride, they are cultural descendants of the steppe nomads. They are like time capsules of pastoral know-how that has been lost. It makes sense that Russia and Kazakhstan are turning to them now for help jumpstarting their cattle industries.

In recent years, the two countries have passed food security laws that allocate a total of $10 billion in government-backed loans for farmers to import breeding cattle, equipment, and cowboy expertise. These programs aim to wean Russia off imported meat by 2020 and Kazakhstan by 2017. They’re making progress. To date, 150,000 cattle and several hundred cowboys now call the steppes their home on the range.

In 2010, I was among the first wave of cowboys going to Russia. I hired on with a team of Montana cowboys transplanting an “ instant ranch Western Horseman

But ever since we left, not a day goes by that I don’t think about my cowboy comrades. I wonder how the cattle and horses have fared. Has a new, authentic “cowboy” culture sprung up, reviving the spirit of Russian cattleman of old?

After five years, I’m going back to find out as a Fulbright-National Geographic Fellow. For my project, Comrade Cowboys

Above all, I’m most excited for another chance to ride horseback across the steppes, the ancestral homeland for cowboys everywhere.

Want to follow along? There are many ways to connect—pick your favorite!

Ryan Bell is a Fulbright-National Geographic Fellow traveling through Russia and Kazakhstan. He’ll report about food topics for The Plate, and his travel adventures for Voices. You can also follow him on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and Storify. His project website is Comrade Cowboys. His most recent piece for The Plate was What Happens When Livestock are In the Path of Wildfire.