Hawai'i is not the multicultural paradise some say it is

The islands still struggle with the legacy of colonialism and the divisions intentionally sown between ethnic groups.

To outsiders, Hawai‘i might seem like the epitome of a post-racial society. For decades, scholars, writers, and tourism boosters have portrayed the islands that way—as a “racial utopia” where Native Hawaiians and Asians live harmoniously alongside white people, with the largely non-white population serving as the antidote to racism.

After all, no racial group holds a majority on the islands, and nearly a quarter of the population reports having a multiracial background. Compare that to the United States as a whole, where only 3 percent of the population is multiracial and three-quarters is white.

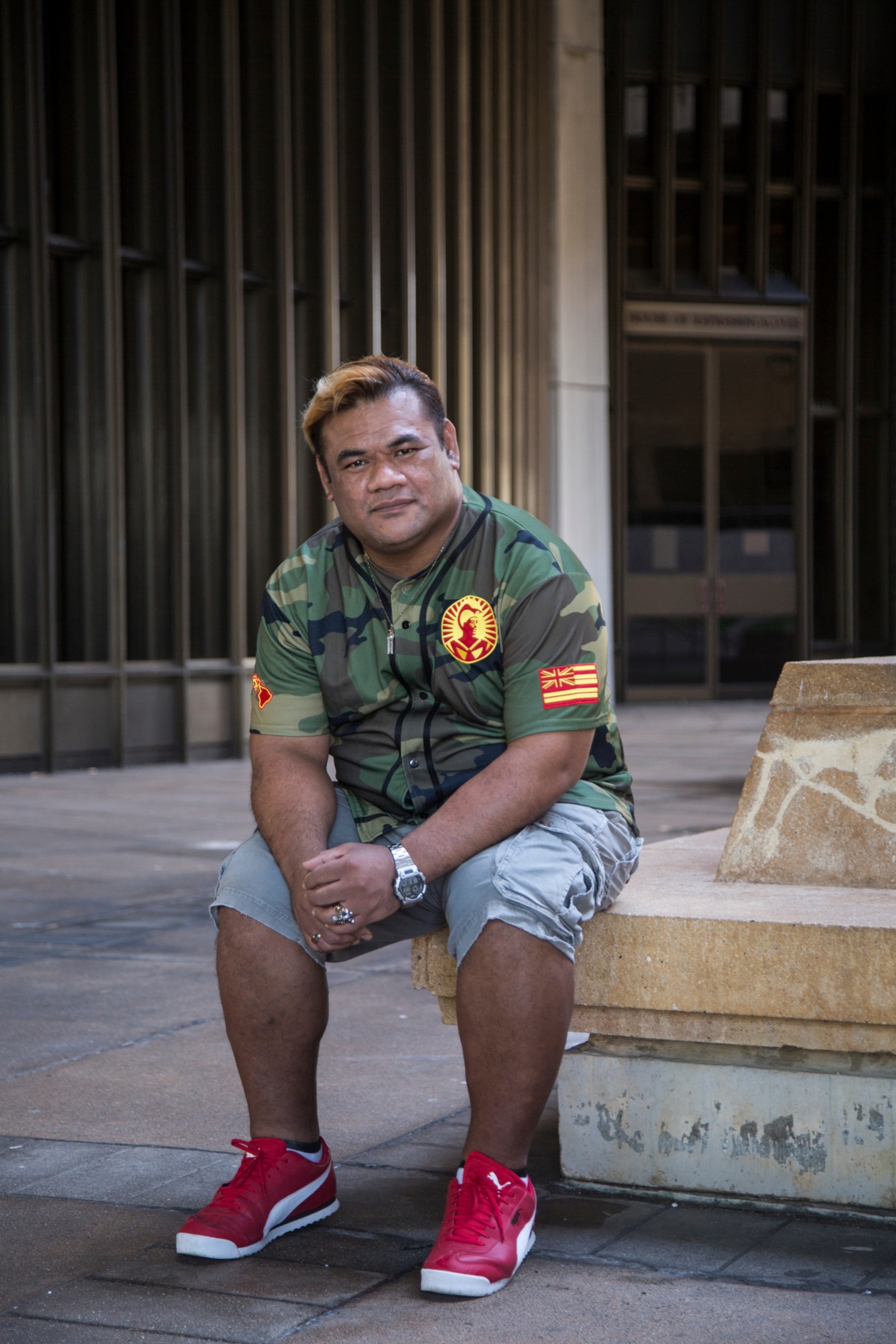

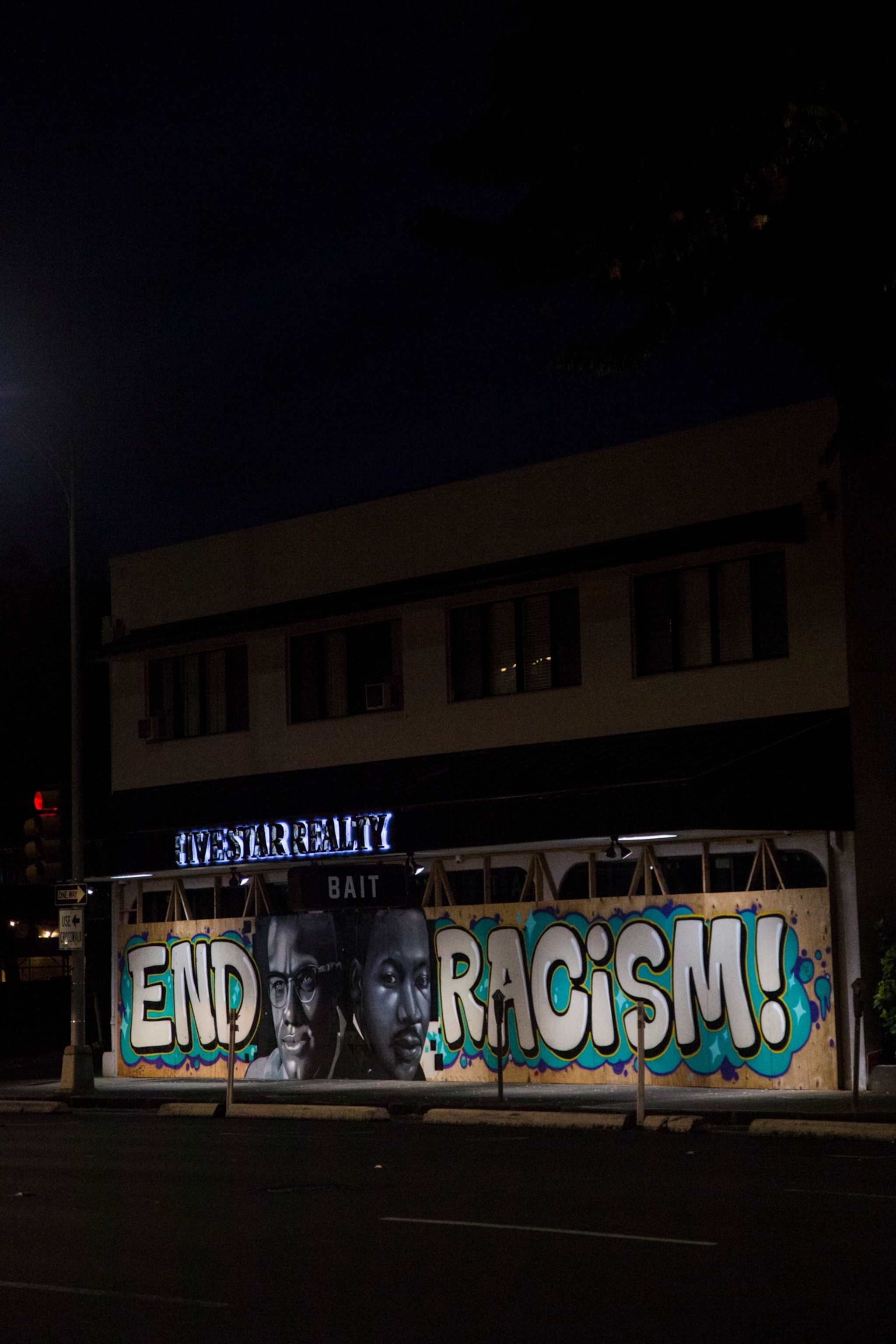

But Hawai‘i’s racial make-up does not stem from a desire to unify races. Instead, it comes from concerted Western efforts to eradicate Native Hawaiian culture and create division among sugar plantation workers. The reverberations are still felt among residents today, including by the people featured in these portraits. Photographed in spaces linked to discrimination against their respective cultures and in places where they find healing from those traumas, they are part of our ongoing project focused on dismantling the myth of Hawai‘i as a post-racial paradise.

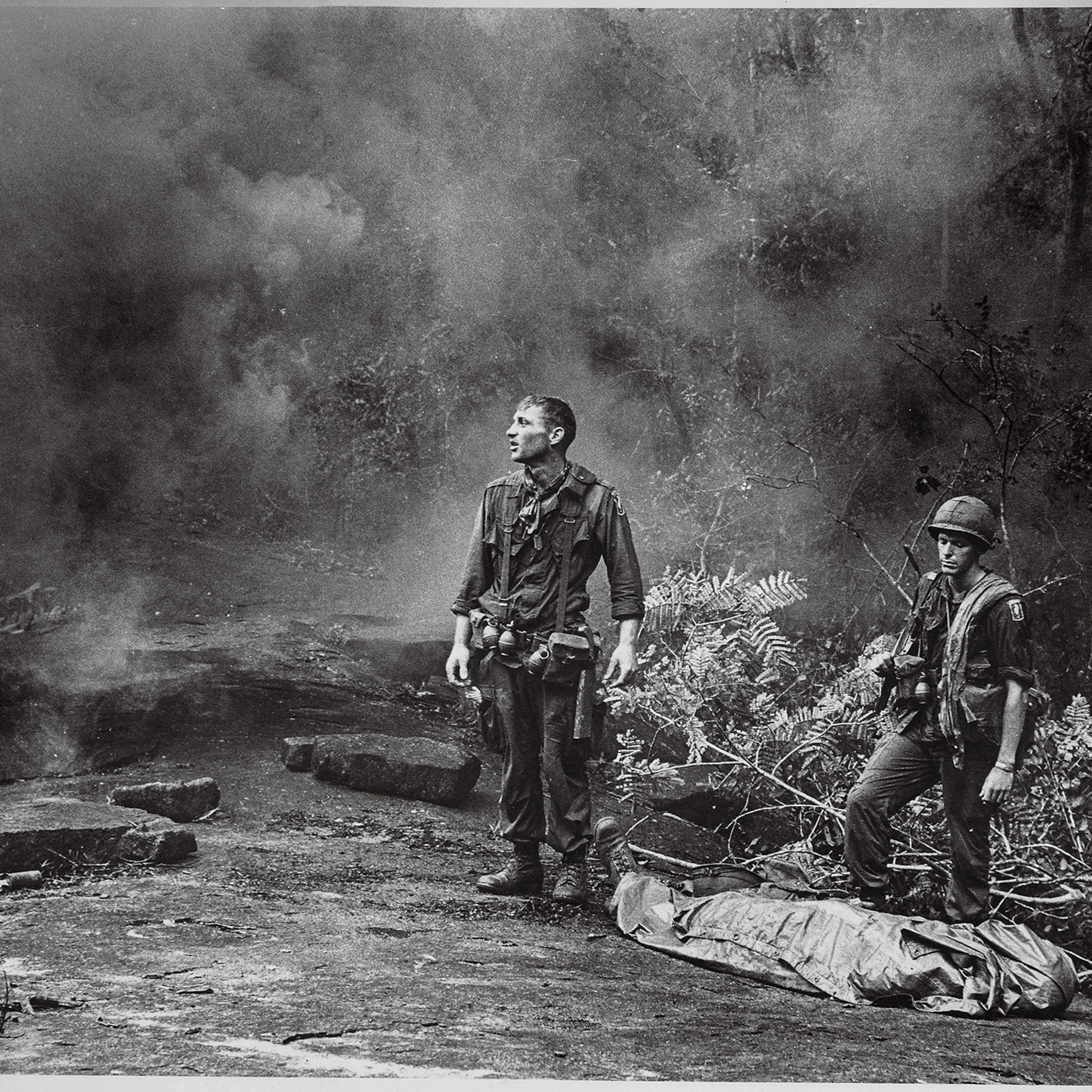

The racial conflict began when Captain James Cook and his men came ashore in the Hawaiian islands in 1778. An estimated 683,000 Native Hawaiians were living in a culturally rich, self-sustaining society and thriving in the ahupuaʻa system—a model for equitably distributing land, resources, and work. The Europeans brought diseases, Western ways of thinking, and labor-intensive sugar plantations, leading to a cascade of traumatic events—including a sharp decline in population, the 1893 illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and what many consider to be an ongoing occupation. (Find out how white planters usurped Hawai‘i’s last queen.)

When Native Hawaiians protested inhumane conditions, owners sought out other ethnic groups for cheap labor on the plantations. Beginning in the 19th century, contract laborers from China, Japan, Okinawa, Portugal, Puerto Rico, Korea, Cape Verde, and the Philippines were lured to the islands with the promise of a paradisiacal lifestyle. Instead, the work was inescapably grueling—especially under the Masters and Servants Act of 1850, which confined laborers to the plantations. “The [Hawaiian] monarchy tried to mitigate against the abuses through personal pressure on the plantation owners,” says cultural historian Adam Keawe Manalo-Camp, but King Kalākaua had been forced to sign the Bayonet Constitution, which greatly limited the monarchy’s power.

Beyond using tactics to increase productivity and profit, plantation owners also made calculated efforts to minimize workers’ power and labor strikes. They segregated ethnic groups, paying them varying wages to incite tension and awarding those with a closer proximity to whiteness with higher pay and positions. Some planters even tried to revive Southern-style cotton plantations on Oʻahu. Laborers were whipped, stripped of their names, and only referred to by their “bango” identification tags. “Much like slave patrols in the South, police officers hunted plantation workers who tried to escape the islands and their indentured servitude, overstayed their contracts, or became unruly according to plantation standards,” says Michael Miranda, chair of the Filipino American National Historical Society, Kauaʻi Committee. Katsu Goto, a Japanese merchant and interpreter, was lynched in 1889 for overstaying his contract, establishing a business, and translating documents from English to Japanese for colleagues. “The cycle repeated: Workers come here, they're mistreated, they save enough to leave the plantation, and violence ensues,” Miranda adds.

Still sociologists in the 1920s and 30s looked at Hawai‘i’s mix of races and ethnicities, and especially the intermarriage among them, and saw the ultimate racial laboratory, where they could conduct race-related studies. Romanzo Colfax Adams, a leading sociologist at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, promoted the notion that Hawai'i was a so-called melting pot. “After a time the terms now commonly used to designate the various groups according to the country of birth or ancestry will be forgotten,” he wrote in 1925. “There will be no Portuguese, no Chinese, no Japanese — only American.”

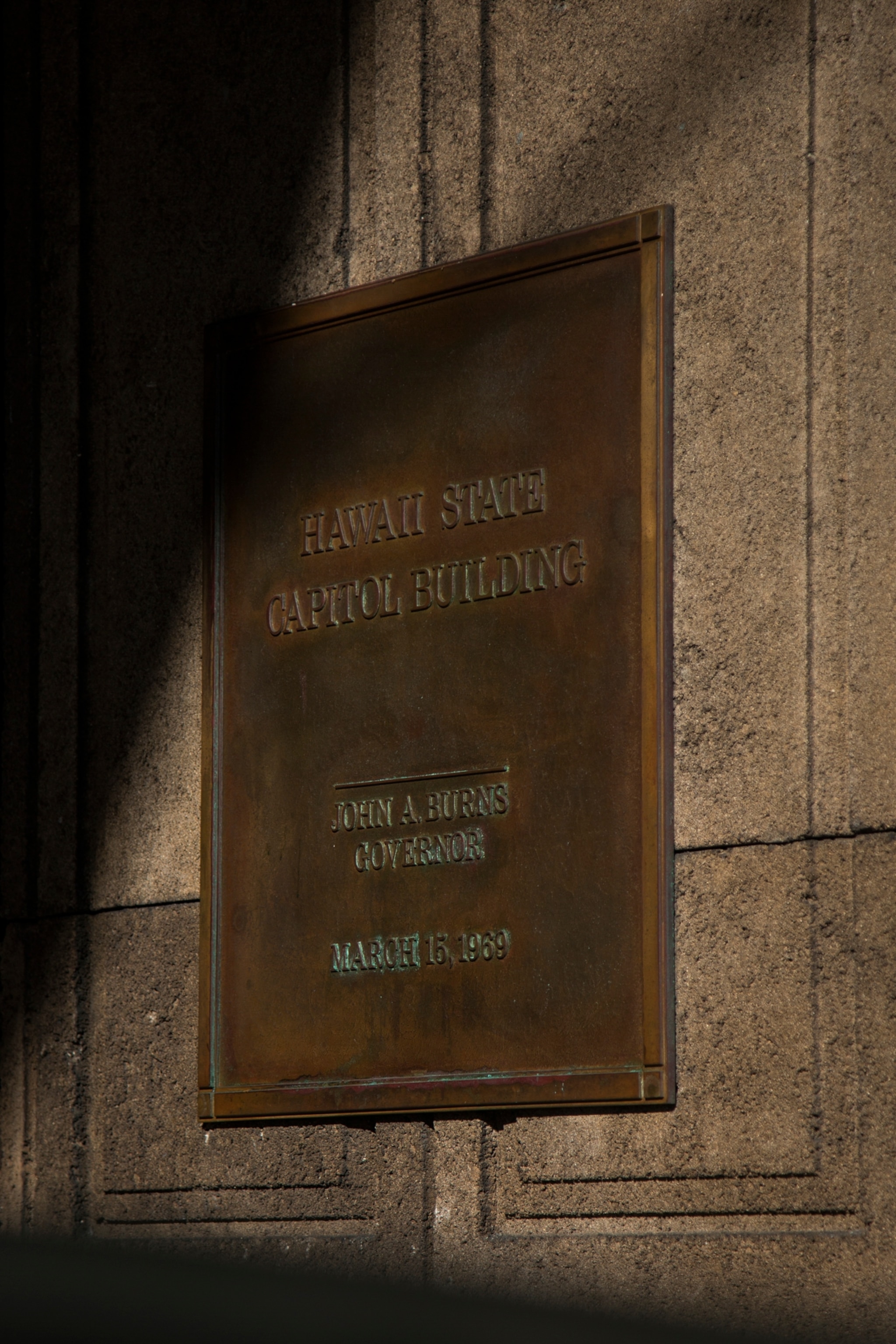

Although modern scholars such as Jonathan Okamura ascribe early intermarriage rates to a sex imbalance among the populations rather than any special tolerance, politicians touted Hawai‘i as a society of “colonial progress” where Asians and Native Hawaiians could culturally assimilate and become “model minorities,” an argument that eventually led to Hawai‘i’s statehood (many Native Hawaiians and non-Hawaiian locals alike often refer to the islands as a “fake state” given the lawless process involved). The concept of a racial utopia was being weaponized to undermine Black struggles on the continent and demonize people of color on the islands for “disrupting racial harmony,” especially in the cases of Myles Fukunaga, who was hanged for murder in 1928, and Joseph Kahahawai, who was falsely accused of rape and murdered in 1931. Nevertheless, by the 1950s and 60s, the tourism industry was selling the “Aloha Spirit,” Native Hawaiian culture, and racial harmony as commodities that visitors could purchase with a plane ticket.

The ethnic hierarchies created during the plantation era still exist today. There continues to be persistent mistreatment of Native Hawaiian, Filipino, Samoan, Micronesian, Black, and Tongan communities, especially within the education, economic, and justice systems. Native Hawaiians have among the highest poverty rates on the islands and make up some 20 percent of Hawaiʻi’s houseless population. Samoans, Tongans, and Filipinos struggle with low per capita incomes, while more than half of Hawai‘i’s Marshallese population are impoverished. Black residents do slightly better financially but account for nearly a third of the state’s reports of race-related employment discrimination. Meanwhile, Japanese residents earn the highest per capita income at $32,129, followed by white residents at $31,621. Both groups dominate the racial make-up of Hawai‘i’s current government.

Samoans, Tongans, and Micronesians face discrimination similar to what Filipinos faced during the plantation era but Micronesians, the most recent immigrants, endure the brunt of it. “Most Micronesians in Hawaiʻi come from nations that have Compact of Free Association (COFA) agreements with the U.S., which allows us to work [here] in exchange for military control of our territories,” says Leeroy Ittu, a former special needs teacher from Kosrae. “Many locals wrongly accuse us of taking jobs away, yet we are also somehow lazy and on welfare. The truth is many of us work at low wage jobs because of discrimination and our political status.”

Hawai‘i isn’t immune to the racial inequities all too familiar in the continental United States. Black and Samoan mothers have the highest infant mortality rates. School curriculums often erase the histories of Native Hawaiians, other Pacific Islanders, and Asians. An enormous telescope is being planned for the sacred mountain of Mauna a Wākea.

Hawai‘i also has one of the highest rates of police killings per capita. In Oʻahu, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders are subject to more than a third of the incidents of police use of force, even though they make up only 10 percent of the population. Just last month, the Honolulu Police Department killed two unarmed people of color: 16-year-old Iremamber Sykap, a Chuukese teenager nicknamed “Baby” as the youngest in his family, and 29-year-old Lindani Myeni, a Black family man originally from South Africa.

We are two non-Hawaiian women of color raised in Hawai‘i; these issues go beyond just being stories for us: They are our own lived experiences and the experiences of those we hold dear. The ethnic divisions erected by the planters more than a century ago are real but they can be overcome with resilience, education, and solidarity. We see hope in movements from the Hawaiian Renaissance in the 1970s to Protect Mauna Kea now, and organizations such the Pōpolo Project, We Are Oceania, and many others that reclaim their cultures through community-building.

“Mau Piailug, the Micronesian master navigator who helped to resurrect Polynesian voyaging, reminded us to resist the imaginary political boundaries that separate us,” says Adam Keawe Manalo-Camp. Or, as the great Fannie Lou Hamer put it, “Nobody’s free until everybody’s free.”

Writer Imani Altemus-Williams is of Black, Jewish and Choctaw ancestry, and is on the board of the Pōpolo Project. Photographer and writer Marie Eriel Hobro is of Filipino, Spanish, and Chinese ancestry. They both live in Honolulu. Please visit Hobro's website for updates and resources on their project.

Note: Special thanks to Adam Keawe Manalo-Camp and all of the participants for their invaluable contributions to this ongoing project.

Editor's Note: This article originally misstated Michael Miranda's title. He is the chair of the Filipino American National Historical Society, Kaua‘i Committee.