Why Maha Shivaratri is one of Hinduism’s holiest nights

Observed with fasting, prayer, and night-long vigils, the festival commemorates ancient stories of Shiva and cosmic creation.

In just one night, the universe was born, good vanquished evil, and a divine marriage shaped humanity. Each year, that momentous evening is commemorated by Maha Shivaratri, a festival inspired by ancient legends of Hinduism's supreme deity Shiva. While Diwali and Holi are perhaps the world’s two most famous Hindu festivals, Maha Shivaratri is the annual event devoted to Shiva.

Shiva is one of the triumvirate of principal gods in Hinduism—the world’s third-largest religion with about 1.2 billion followers, most of whom reside in India. Some Hindus worship Brahma the creator god, while others prefer to pray to Vishnu the preserver, or Shiva the destroyer. This latter group is called the Shaivites, and has more than 300 million members.

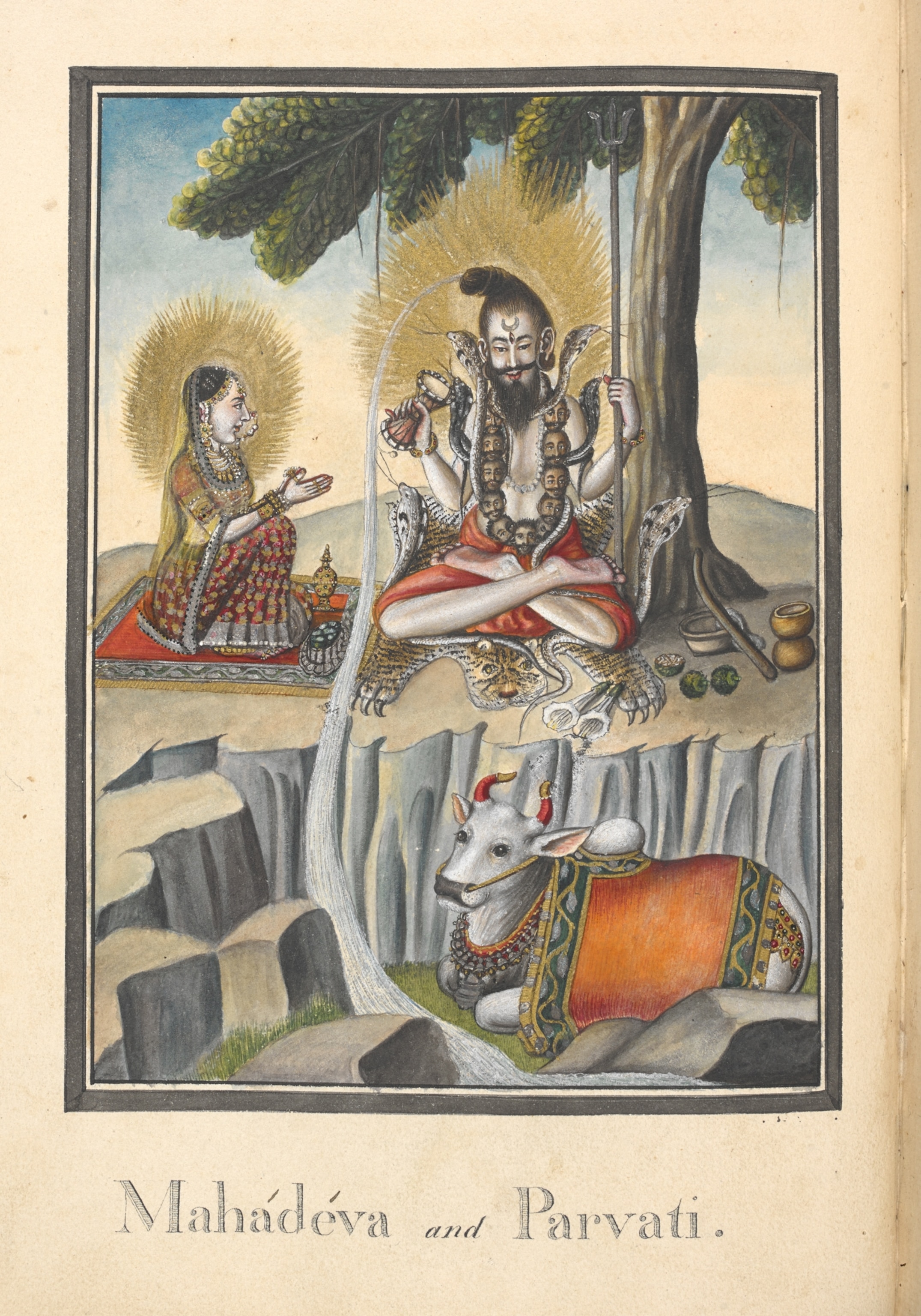

Maha Shivaratri, also known as the Great Night of Shiva, commemorates the deity’s life marriage to Goddess Parvati, his brave acts that saved our planet, and the lord’s cosmic dance which evokes the life cycle. Here’s what you need to know about the stories behind this Hindu celebration.

The countless expressions of Hinduism

Hinduism is an ancient religion, dating back more than 4,000 years, and scholars generally believe it originated in the Indus Valley between 2300 B.C. and 1500 B.C. Due to the religion's vast collection of ancient texts and regional diversity across the Indian subcontinent, its festivals are inspired by a plethora of myths. Maha Shivaratri is no different.

“Hindu festivals are marked and celebrated in diverse ways in India’s different linguistic and cultural regions, as well as in diasporic contexts,” explains Amy Allocco, professor of religious studies at Elon University in North Carolina. The way festivals like Maha Shivaratri are celebrated also differ based on region and source material. “These variations are observable in many dimensions of festival performances, including narrative, ritual, and culinary practices.”

What these religious festivals have in common are acts of devotion directed to one or more Hindu deities. During Maha Shivaratri, participants may perform a ritual bathing or provide offerings to the gods like jujube fruit or bilwa leaves. “Devotion to the deity helps to subordinate the ego to a power greater than ourselves, and worship reinforces this, as well as creating a sense of the real presence of the deity in one’s life,” says Jeffery D. Long, a religious studies professor at Elizabethtown College in Pennsylvania whose research centers on the religions and philosophies of India.

No matter the origin story, the holiday of Maha Shivaratri is fundamentally linked to the creation of the universe in the Hindu culture.

Celebrating the divine marriage

One of the most prominent legends associated with Maha Shivaratri is the divine marriage between Shiva and Goddess Parvati. The union is said to have given birth to the universe by uniting pure consciousness (Shiva) with creative energy (Parvati), bringing balance to the cosmos. Their marriage, often depicted as the Hindu deity Ardhanarishvara, is said to have released the necessary force to create and sustain life.

This legend makes Maha Shivaratri especially relevant to Hindu couples, says Indian philosophy and Hinduism expert Purushottama Bilimoria. Bilimoria is also a principal fellow at Australia’s University of Melbourne.

“For many Hindus, the wedding night is not understood as an individualistic or merely private event,” he says. “But instead as a cosmic moment, one that symbolically inaugurates the coming-into-being of the universe itself.”

Shiva represents consciousness and spirituality, while Parvati embodies devotion, fertility, and responsibility. This symbolic polarity is reflected within many Hindu marriages, Bilimoria explains. “Couples are encouraged to cultivate a comparable balance—one that promises mutual fecundity, prosperity, fidelity, longevity, and compassion,” he says. “They pray together, partake in feasting while also observing periods of fasting, enjoy the legitimate pleasures of life (puruṣārthas), and raise progeny.”

Shiva’s cosmic dance of creation

For some Hindus, Maha Shivaratri also commemorates the Tandava—Shiva’s dance of creation, preservation, and destruction. When performing the Tandava, Shiva took the form of the cosmic dancer Nataraja. Also called Lord of the Dance, Nataraja can be traced back more than 1,500 years to its depictions in Indian sculptures.

This performance represents the continuous rhythm of the universe and the balance between dynamic energy and internal stillness.

“As such, on a cosmic level, Shiva’s dance is going on all of the time,” says Long. “We are all part of it. But it is associated with this particular night (of Maha Shivaratri) because nighttime—as a time when things are traditionally very quiet and the world is sleeping—represents the creative point just before Shiva begins his dance of manifesting the world.”

How Shiva guarded the planet

Beyond these legends of creation, Maha Shivaratri is also tied to Shiva’s role as a protector of the universe. According to Long, in one legend Shiva asserts his supremacy over deities Brahman and Vishnu by taking the form of an infinite column of light. Often known as Jyotirlinga, this luminous column symbolizes Shiva’s limitless power.

Shiva’s courage is further underlined by two more legends intertwined with this festival. In one, a poison threatens to engulf and destroy our world until Shiva steps in and pours the toxic potion down his holy throat, ensuring humanity survives. In another, Shiva fires an arrow to destroy three citadels commanded by demonic brothers Kamalasksha, Tarakaksha, and Vidyunmali—a dynamic metaphor for the conquest of evil by good.

How Maha Shivaratri is celebrated

Maha Shivaratri’s spiritual significance is enhanced by its unique spectacle. On this day, India becomes a literal land of milk and honey. Worshippers pour those sweet liquids over shiva lingam, a cylindrical object displayed in many temples and homes, which represents Shiva’s limitless column. They do this all while chanting the mantra “Om Namah Shivay” (I bow to Shiva).

Festival participants may purify themselves by bathing, show piety via fasting, find peace in meditation, honor Shiva with burning lamps, and chant mantras en masse at glowing Hindu temples.

Each of these evocative myths reside amid the color, theater, and spirituality of Maha Shivaratri, a complex festival that is Hindu in nature, rich in lore, eclectic in ritual—yet symbolically relevant to all.