These detectives want your help in finding Nazi-looted art

The Monuments Men and Women Foundation is on the hunt to recover stolen masterpieces—and they say this could be our best chance to find them.

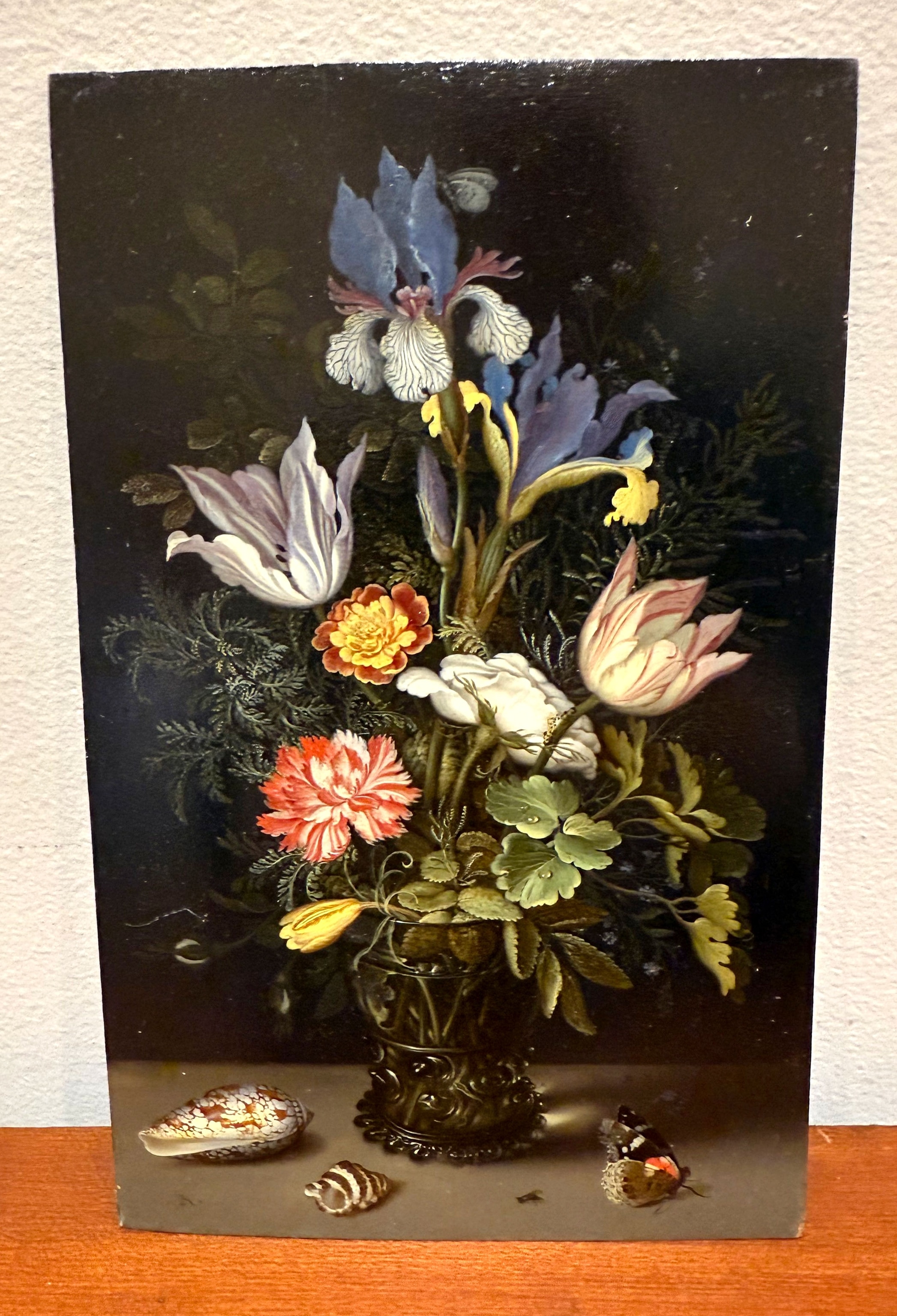

In Newark, Ohio, two small 17th-century paintings sat on the auction block in September 2025, awaiting their next stops. Each had a delicate composition of items—a tulip, a rose, a butterfly suspended mid-flight—arranged with such precision that it seemed almost alive on the canvas. The auction house listed the paintings with modest estimates: For one, the highest bid was just $225.

The first clue that these were not ordinary still lifes came from the internet. A few vigilant art lovers, scrolling through online listings, noticed something peculiar: The backs of both paintings were marked with curious handwritten letters and numbers—S 16 and S 17.

To most, the writing would mean nothing, but to anyone familiar with the vast Nazi plunder of European art, it was unmistakable. The S stood for Schloss—as in the Adolphe and Lucie Schloss collection, one of France’s premier collections of Dutch and Flemish masterpieces before World War II. Adolphe and Lucie Schloss were Jewish, and their carefully curated collection was, like millions of other works of art, stolen by the Nazi regime.

The two still lifes disappeared in 1943 and are far more valuable than the Ohio auction house knew. They are the work of Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder, a 17th-century Dutch painter whose elegant approach to floral still life was groundbreaking. Where the two paintings spent the past eight decades, and how they traveled from Europe to the United States, is still a mystery and will likely remain one. Their discovery was the result of work by the Monuments Men and Women Foundation, a nonprofit that continues the hunt for Nazi-plundered art.

The foundation quickly confirmed the provenance of the paintings. Both were listed in the database of the Jewish Digital Cultural Recovery Project Foundation, a record of the Schloss collection and other Jewish-owned objects that were plundered between 1933 and 1945, confirming that the paintings were stolen from the Schloss family. Time was of the essence: The auction was set to close in less than two weeks. “Anybody on the internet could realize that these were actually worth more than the $250 they were being offered at,” explains foundation president Anna Bottinelli, who leads a small team of researchers and volunteers who monitor tips from around the world. The paintings, she points out, are small enough to fit into a backpack, and could easily have been stolen by someone who knew their value.

Within 24 hours, the foundation’s chairman and founder, Robert Edsel—whose 2009 book, The Monuments Men, inspired the 2014 George Clooney film—was on a flight to Ohio. “The priority was to ensure the safety of the works,” Bottinelli says. The team contacted the auction house, which had unknowingly listed looted paintings for sale, and shared the evidence linking them to the Schloss collection. To the foundation’s relief, the owners were cooperative. The paintings were withdrawn from sale and placed in the auction house’s safe pending restitution.

The long tail of Nazi-looted art

The recovery of the Bosschaert paintings was one of the foundation’s most dramatic recent successes—and a reminder that the work of the Monuments Men and Women Foundation is far from over.

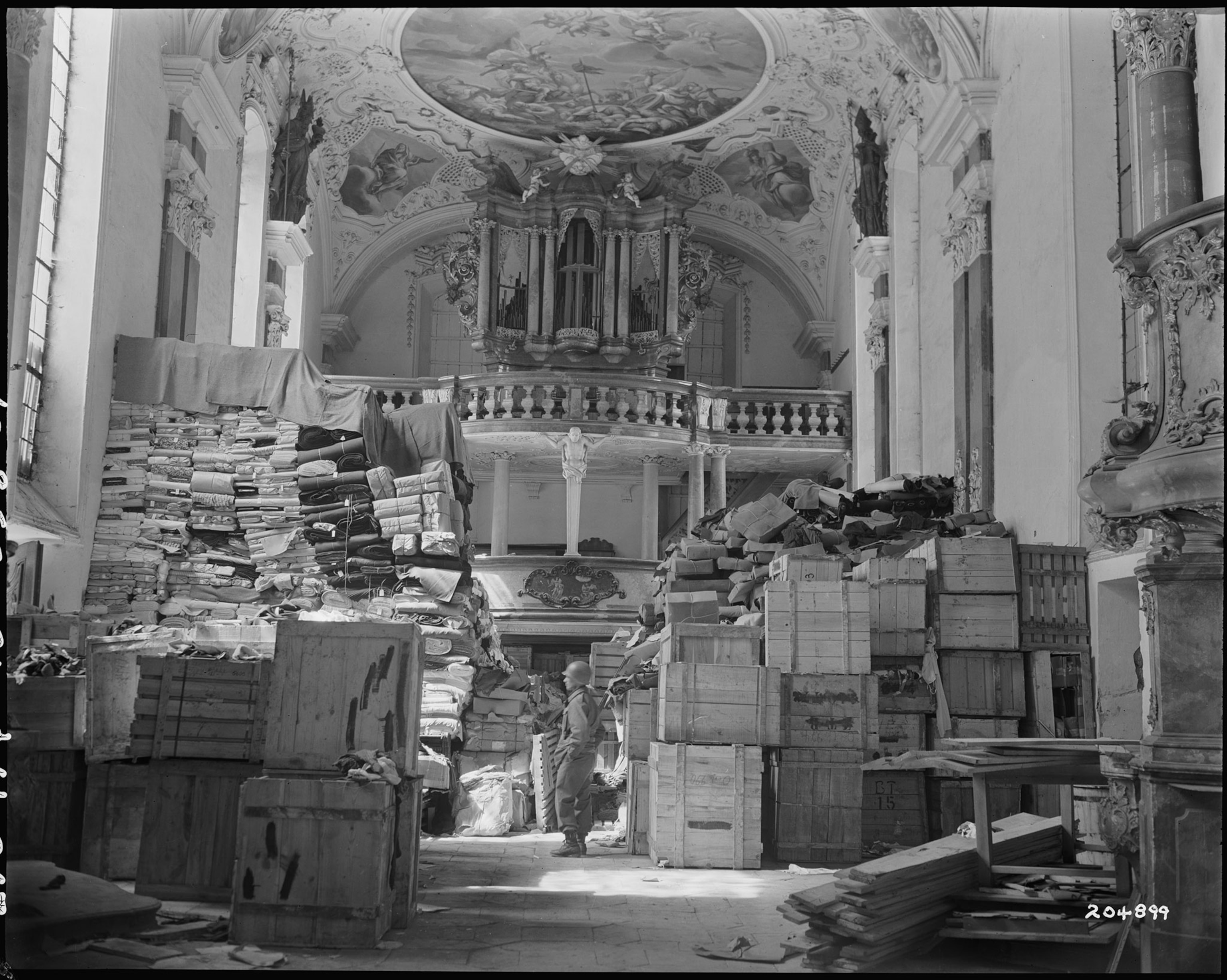

During World War II, the original Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives (MFAA) program—popularly known as the Monuments Men—was composed of roughly 350 men and women from 14 nations. They were museum directors, curators, art historians, and conservators, many of whom traded their tweeds for fatigues. As Allied forces advanced through Europe, the MFAA officers followed close behind, identifying bomb-damaged churches, cataloging rescued works, and uncovering caches of looted treasures hidden in salt mines and castles. They recovered somewhere in the range of five million pieces of art, including Michelangelo’s “Bruges Madonna” (1503-05) and Édouard Manet’s “In the Conservatory” (1879).

For every painting tracked down and returned, countless others remained missing. Some were destroyed; others were hidden away in private collections, passed down quietly through families who never knew, or never asked, where the art had come from. Historians estimate that nearly 20 percent of artwork in Europe was stolen by the Nazi regime, in many instances through outright plunder and in others through forced sales as Jewish collectors were compelled to sell their pieces for significantly less than they were worth. Today, more than 100,000 pieces are still missing, spread out across the globe.

Among those 100,000 pieces are hundreds of paintings that were part of the Schloss collection. After the deaths of Adolphe and Lucie Schloss in the late 1930s, the collection passed to their four children, who moved hundreds of pieces of art to a château in the Loire Valley, hoping to keep them safe from plunder. In 1943, the Vichy government paved the way for seizure of the entire collection. More than 200 paintings were earmarked for Germany—destined for Adolf Hitler’s planned Führermuseum in Linz, Austria (Hans Posse, appointed by Hitler to source art for the museum, wrote specifically about the Schloss collection in his diaries in 1940, noting names and location), or for the personal collections of senior Nazi officials—while another 49 were diverted to the Louvre in Paris, where curators quietly inventoried and stored them even as the museum outwardly resisted overt collaboration.

By the time the Monuments Men reached Germany in 1945, the core of the Schloss collection had already vanished, and more than 150 pieces have yet to be found. How two of them ended up in Ohio is a mystery.

In 2007 Edsel founded the Monuments Men and Women Foundation to continue the quest to return recovered works of art to their rightful heirs, relying on the foundation’s own work and the help of the public. The foundation operates at the intersection of scholarship, diplomacy, and detective work. The organization’s researchers sift through archives, contact descendants of victims, and collaborate with museums and auction houses. They also train appraisers and estate professionals to recognize markings and catalog numbers that could indicate looted art.

“We cannot have eyes everywhere,” Bottinelli says. “But we can make sure that as many people as possible know enough to be our eyes.” The foundation operates a 24-hour hotline and an online portal for tips, which arrive from art dealers, collectors, and occasionally casual browsers who notice something suspicious online.

Every lead is logged, cross-checked, and investigated—often through international databases, auction records, and archival Nazi inventories. The foundation’s researchers work across time zones, with part of the team in Europe and part in the United States, ensuring near-constant coverage.

“We’re very diligent and proud to never miss or dismiss any lead, as far-fetched as sometimes they may seem,” Bottinelli says.

(Archaeologists train 'Monuments Men' to save Syria's past.)

A rare breakthrough

Lara Yeager-Crasselt, Aso O. Tavitian curator of early modern European painting and sculpture at the Clark Art Institute, explains that Bosschaert was a pioneer of Dutch still life painting, working in the early 1600s at the dawn of the Dutch Republic’s Golden Age. Born in Antwerp to a Protestant family, Bosschaert fled religious persecution and resettled in Middelburg, a bustling port city in the Netherlands. There, surrounded by botanical gardens and maritime trade, he encountered exotic plant specimens arriving from Asia and the Americas. His still lifes—meticulous, luminous, and impossibly detailed—were as much scientific studies as artistic marvels.

The two paintings recovered in Ohio, Yeager-Crasselt says, “are very fine as objects, as works of art, incredibly beautiful and done from a very careful observation of these natural objects, also probably working from drawings and other prints.”

Collectors prized Bosschaert’s works not only for their craftsmanship but also for their symbolic resonance. In an era when tulip bulbs were worth fortunes and botanical curiosity symbolized status, his paintings became emblems of both learning and luxury. “One of his paintings once sold for a thousand guilders,” Yeager-Crasselt notes. “That was an enormous sum at the time—that emphasizes just how valuable these images were.” For context, an unskilled laborer working during the time Bosschaert was painting might earn 300 guilders in a year.

Bosschaert’s paintings continued to be highly prized throughout the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, and they entered the Schloss collection in the late 19th century. The collection was legendary among scholars for its breadth of Dutch and Flemish art. Images of the family’s home show walls covered from floor to ceiling in paintings, arranged in a tableau personally overseen by Adolphe Schloss.

The Ohio discovery marked a rare breakthrough, and once the provenance was verified, the foundation sprang into action. “In most cases, we work directly with the owners or auction houses for voluntary restitution,” Bottinelli explains. “They’re generally very meaningful moments, very rewarding and heartwarming because it’s everybody doing good.”

Still, the process can be delicate. Legal jurisdictions differ, and each case presents its own complications. “We’ve returned more than 40 objects—from paintings and sculptures to tapestries and books—to families and institutions across Europe,” Bottinelli says.

Bottinelli points out that the current moment is a pivotal one in the quest for recovery of stolen art. “Objects that come from attics or basements of relatives, especially if there were veterans—there are less World War II veterans now,” she says. “That generation is dying, and that means that everything that they own will have a new owner [or] will be thrown away. In fact, we often worked with appraisers because they are really the people that need to be trained to distinguish.”

(Remains of a secret Arctic Nazi base reveal a forgotten chapter of WWII.)

Eighty years later, the search for stolen art continues

The foundation is actively seeking documentation that will help them both find looted objects and identify pieces that remain hidden. A series of bound albums, designed to serve as catalogs for Hitler and other high-ranking Nazi officials and that hold photographs of stolen pieces, are of particular interest. Created by the Reichsleiter Rosenberg Task Force, a Nazi organization charged with collecting and cataloging looted goods, many of the books were assembled for Hitler’s personal use.

“At the end of the war, only about 39 of these were found, but we know that there were as many as maybe a hundred. We’ve found four of them since 1945,” Bottinelli says. “They are invaluable documents, and they were used as proof during the Nuremberg trials to show the systematic looting that the Nazis had done.” To someone not versed in the history of looted art, they might look like standard art catalogs or books, but finding any that remain intact could assist in locating stolen and missing artwork.

The foundation has also made a push to educate the public. Among their initiatives is a deck of playing cards printed with 52 of the most wanted missing works of art. Each card features a color image and a short description of masterpieces by painters like Rembrandt van Rijn, Gustav Klimt, and Anthony van Dyck that vanished during the chaos of war. “We hope people will see one of these images and recognize it somewhere,” Bottinelli says. “You never know. Someone might see a painting at a dinner party and realize it’s on our list.”

Eighty years after Allied officers crawled through tunnels to rescue paintings from salt mines, a small team scrolls through digital archives and online auction listings, keeping the same faith. The tools have changed; the mission has not.

“Sometimes it’s as simple as a phone call or a Facebook message,” Bottinelli says. “But that’s how this work happens, one lead at a time.”

In Newark, Ohio, the two Bosschaert paintings are now safely off the market and will eventually be returned to the descendants of their rightful owners. For Bottinelli and her team, it’s another victory—but also a reminder of how much remains to be done.