Navigating the complexities of the Asian American experience amid rising racism at home

When news broke of the shooting in Atlanta that killed eight people, including six Asian women, fury and grief raged in this writer’s heart.

I was grading my students’ final stories when a friend alerted me to the recent news that a man in Atlanta had shot and killed eight people, including six Asian women.

Fury and grief raged my heart. The crime—following thousands of other reports of harassment and attacks against Asian Americans—struck at one of my greatest fears growing up. For a second, I was a child, afraid to get out of my dad’s car at a truck stop in Georgia during a family trip.

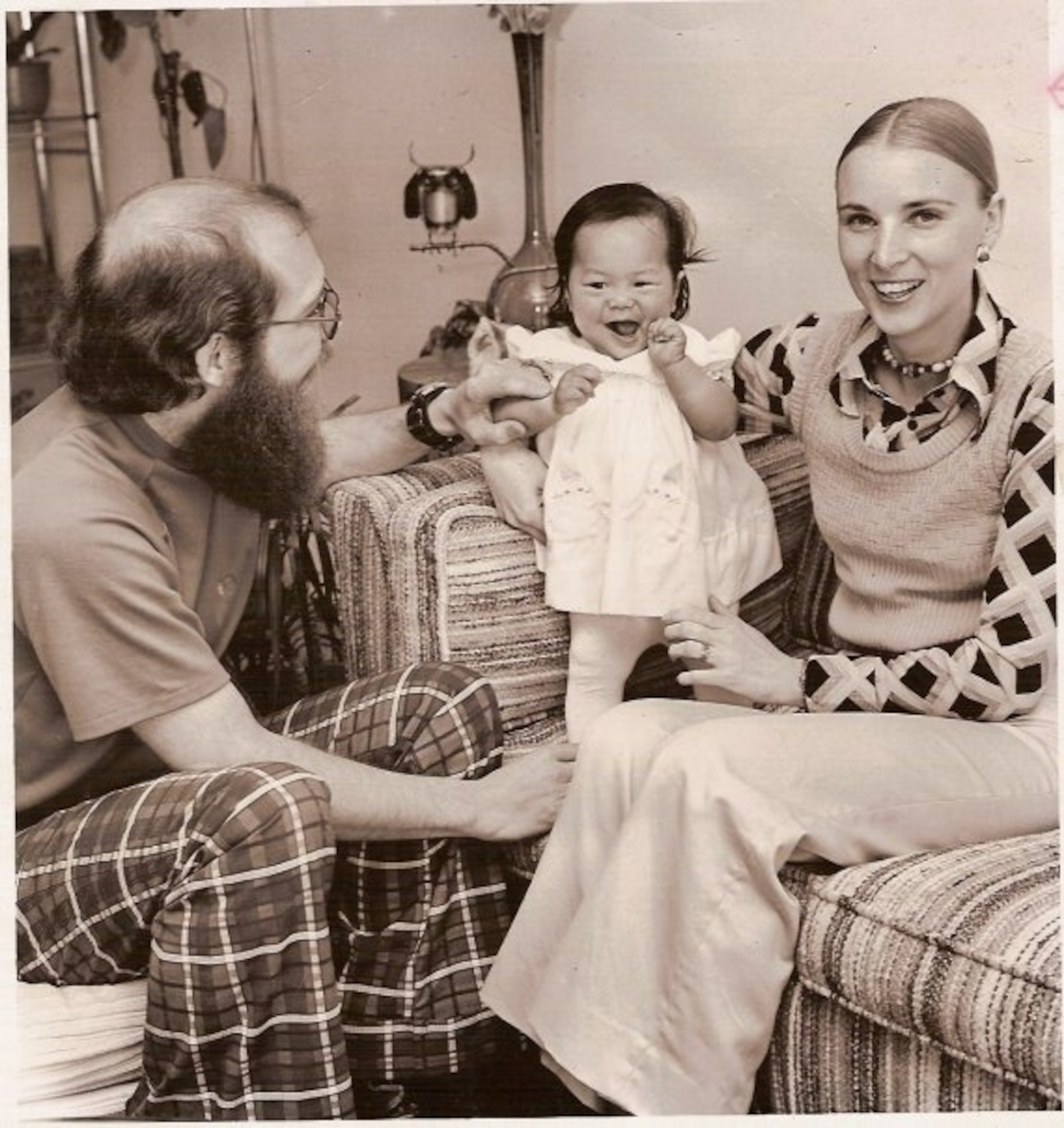

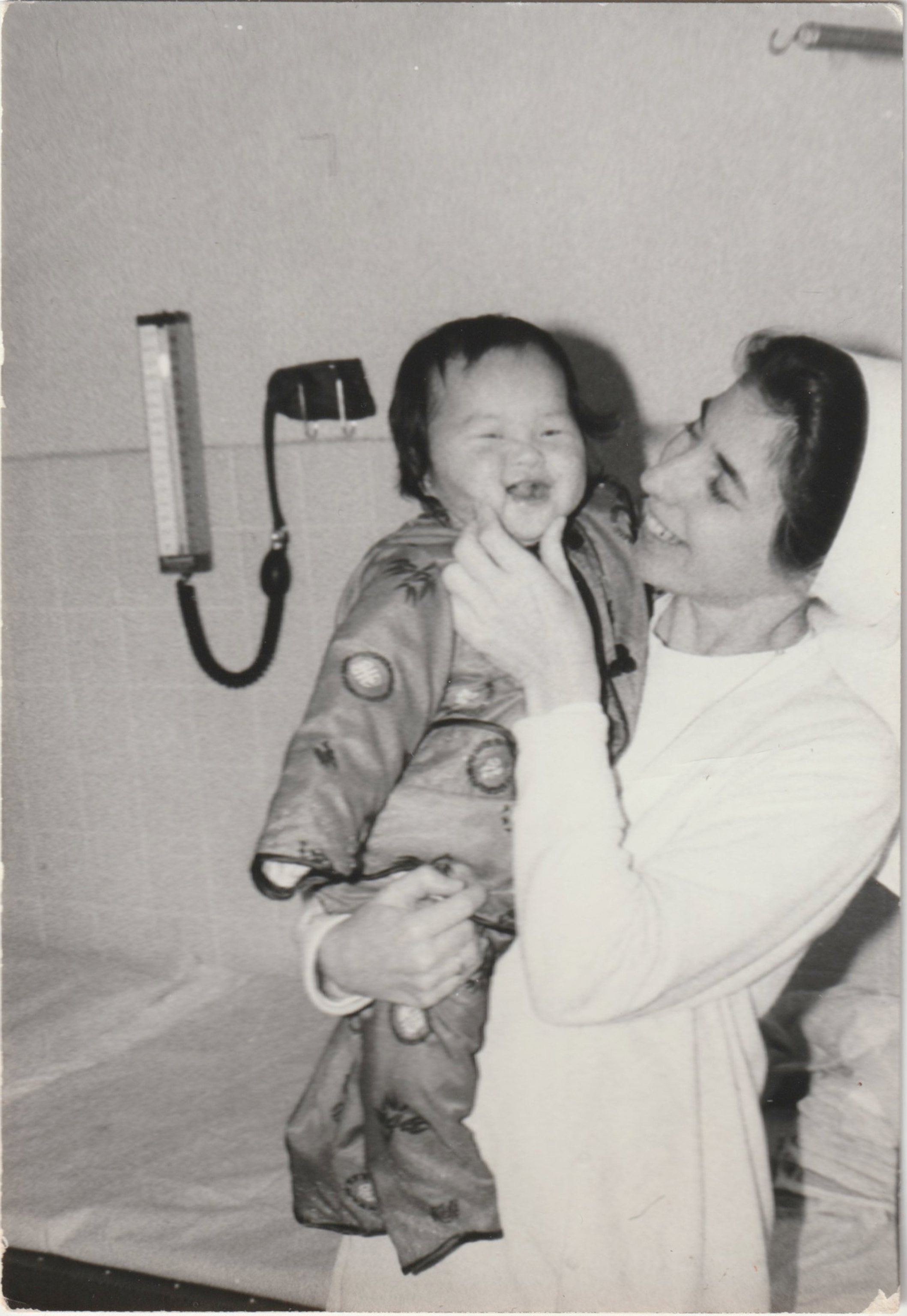

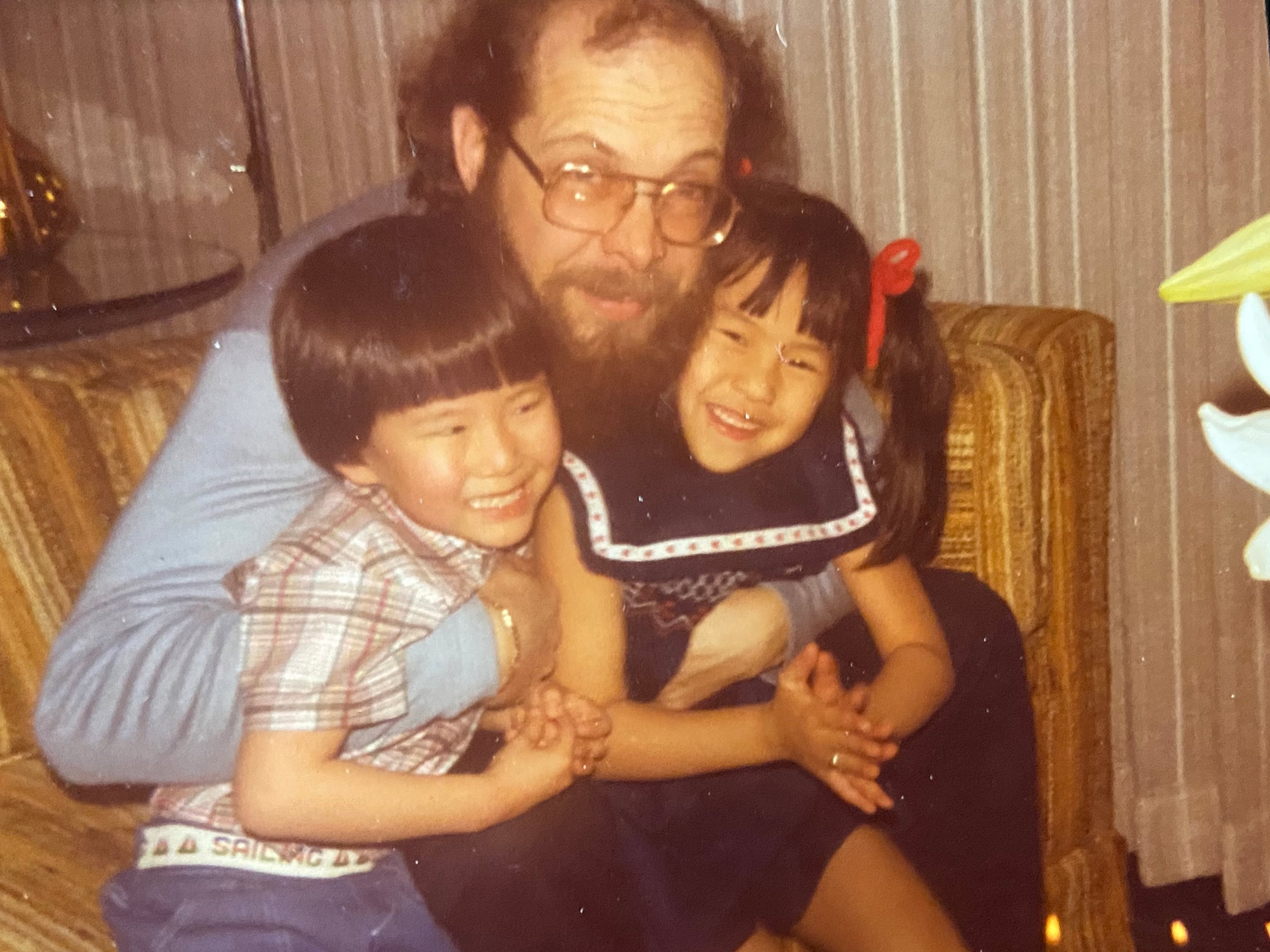

I was raised in suburban Detroit, the adopted Chinese child of two white parents. Taylor, Michigan, was a blue-collar, union town. The population was mostly white. I used to joke that my Korean brothers and I made up a hearty portion of the less than 1 percent that was Asian. My dad was a teachers’ union leader, and my mom was an elementary school principal. We stood out, in good ways, for our grades and involvement in the community. Our family and our story were well-known. My birth parents in Taiwan had given me up, because they were poor, had too many daughters and wanted a son.

People always used to ask me, “How does it feel to be adopted?”

To me, this seemed impertinent; my family was close, and our dynamics seemed like any other.

The underlying—and more painful—question they were asking was: “How does it feel to be Asian?”

The case and its outcome scared my parents. They tried to talk to us about racism, and looked for ways for us to be around Asian Americans. But I did not let on to them the types of things people said to us—or how often. I wanted to protect my parents from something that I knew they could not stop.

I heard racial slurs regularly. In my memory, a blurry amalgamation of perpetrators carried out the offenses: a car full of young white men yelling, go back to “your country”; the teen who taunted “Ching, chang, chong!”; the woman whose eyes followed me and my family. I refused to get out of the car during bathroom breaks at remote gas stations as we drove south to Florida on vacation. I hated the prickling feeling of the stares.

No one ever physically hurt me, but even as a child, I sensed a fine line between insult and injury.

I came to believe that culture and identity are choices that evolve, and not just something you are born with or that society imposes on you.

Mei-Ling Hopgood, Author and Professor at Northwestern University

And, anyway, I thrived; I did well in school and had lots of friends. I went out of my way to prove how American I was: pompom squad, student council, perfect English. I wanted to be anything but Asian.

Relieved to move on

I was relieved to get out of town and that period of my life, leaving at 17 years old to attend university and start traveling the world. I chose to study Spanish, instead of Mandarin. I remember staring at the racks of multicolored fliers advertising programs in different countries. I avoided red (China), and chose green (Mexico). During my first year of college, I’d walk around campus, acutely aware of every other Asian person I saw—and that I saw them as foreigners. That’s how people must see me, I thought. I began to face my self-loathing and ignorance.

I found my own voice with support of communities of color. As a radicalized college student, I became strident in response to the wounds of the past. When I visited home, I argued with people from high school about their anti-Asian or anti-Black views. Once, I heard a group of kids say “Ah-so!” behind me, while my family and I were buying popcorn at a movie theater.

“You think you are more American because you are white?!” I screamed and swore at the kids, who cowered. The crowd lobby seemed to stop moving. I stood before them, smoldering.

Questioning where I fit in

But I shrugged it all off—even laughed. Abroad, I was an outsider of my own design. I could be whomever I chose, and it didn’t feel personal.

I came to believe that culture and identity are choices that evolve, and not just something you are born with or that society imposes on you. I lived in South America for almost eight years, before returning to the United States in 2012, to become a professor of journalism at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. I am in awe of the diversity on campus. Almost half of the Class of 2024 are students of color, including 25 percent Asian American. Their experience seems so different from when I went to school. Discrimination remains a pervasive problem in the U.S.—the justice system, in higher ed, in newsrooms, in Hollywood—you name it. But I can see progress in the world our students represent and envision.

The COVID backlash expected

But there are so many other important national discussions going on and everyone was trying to survive the pandemic; this particular cause seemed almost invisible.

I emphasized the importance, too, of stories of joy, success, and survival. The course felt deeply personal and consequential, especially at this time, for me as much as anyone. My students know I’m a crier—and I didn’t disappoint on the last day of class.

My hope is that my students will be among them one day. This nation must see that the stories of Asian Americans are an important part of the collective narrative of racial experience in the U.S. And the reckoning must include their voices.

Mei-Ling Hopgood is a freelance journalist and writer who has written for various publications, ranging from the National Geographic Traveler and Marie Claire to the Miami Herald and the Boston Globe. She has worked as a reporter with the Detroit Free Press, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and in the Cox Newspapers Washington bureau.