Our Historic Relationship With Alcohol: It’s Complicated

The European settlers’ drinking habits in the early days of the American Republic were pretty extensive. They topped out at around 4.15 beers a day or 7.1 gallons of pure alcohol per person per year in the 1830s. That’s pretty staggering when you realize that modern U.S. Dietary Guidelines suggests no more than one drink per day for women and two for men. So were we just a bunch of alcoholics?

Well, it’s much more complicated than that, says Washington, D.C.’s National Archives curator Bruce Bustard, who oversees Spirited Republic, an exhibit chronicling Americans and our love-hate relationship with alcohol from the first colonists up to the 21st century. “It sounds like people were staggering around all day, but that’s not true,” he says.

“In early America, drinking alcohol was an accepted part of everyday life at a time when water was suspect and life was hard … Men, women, and even children swallowed ‘a healthful dram’ with breakfast,” Bustard says.

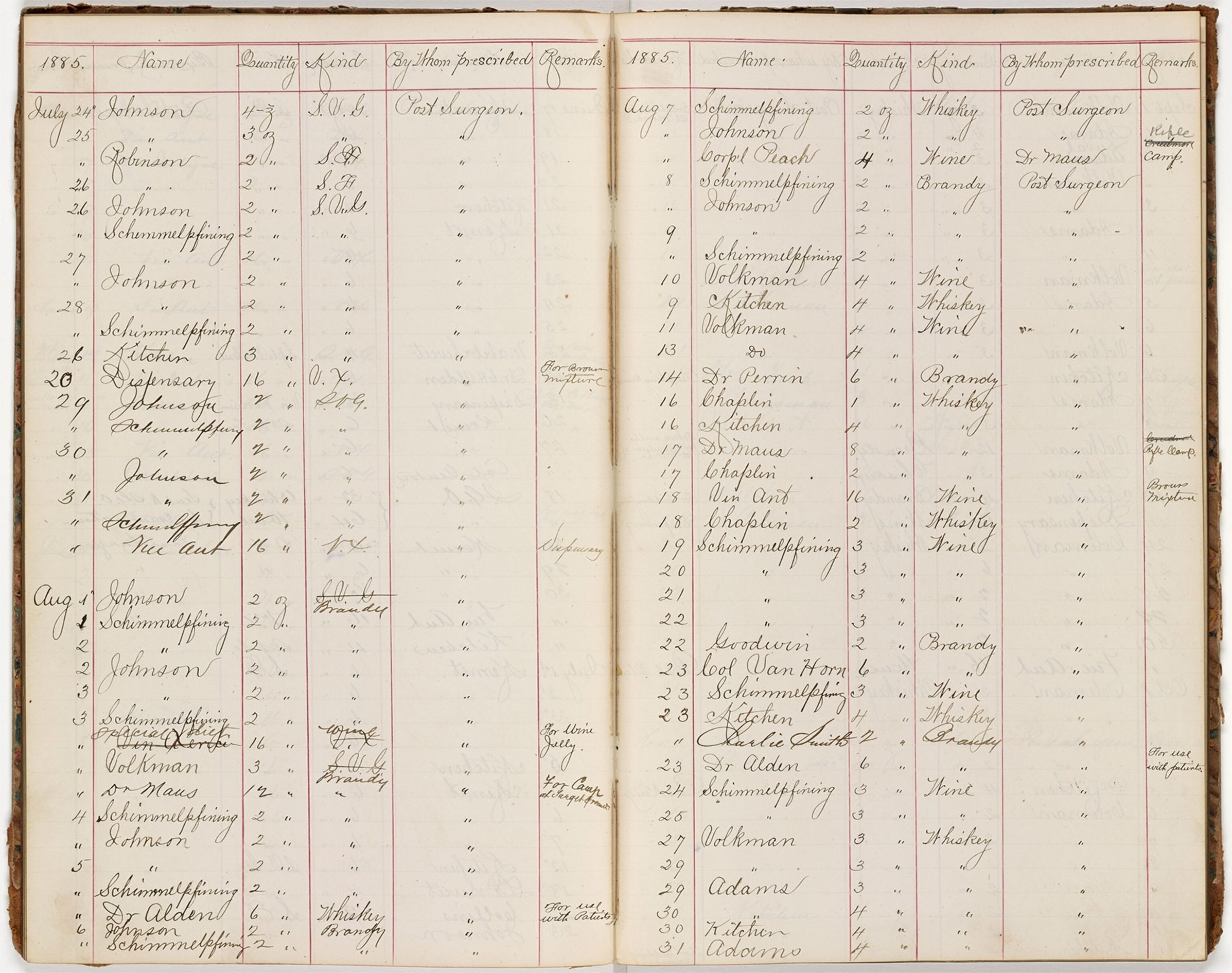

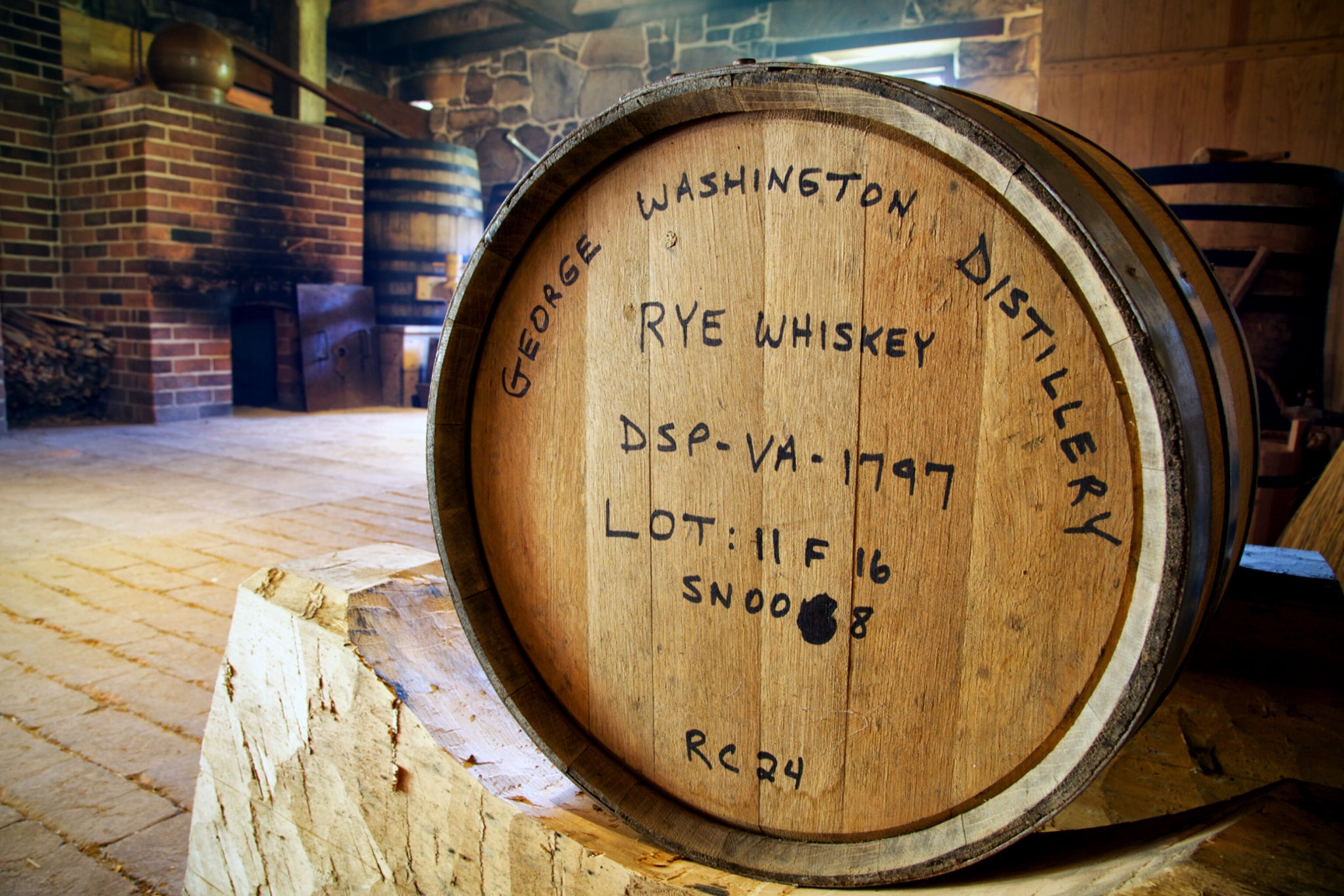

There once was a wide acceptance—even an embracing—of alcohol. Troops that joined the Continental Army were rewarded with a ration of whiskey or some kind of beer, our first president had a rye whiskey distillery at his home in Mount Vernon (which opened to the public in 2007). As part of a religious wave of perfectionism, coupled with witnessing the family and health havoc associated with what too much alcohol could do, the fevers of Prohibition took hold around 1920. But alcohol didn’t disappear. Speakeasys popped up in major cities, moonshine distilleries grew in the countryside, and doctors even prescribed alcohol as medicine.

While today’s 2.3 gallon average of annual alcohol consumption pales in comparison to our forefathers, foremothers, and forechildren, that doesn’t mean we don’t draw inspiration from their cups. In fact, walking into any half-decent bar today and perusing the drinks menu means taking a virtual walk through history, as bartenders experiment with punches, tonics, and shrubs (not the ones in your backyard.)

And the hard stuff is coming back, too. The amount of rye whiskey produced has grown a whopping 536 percent since 2009, according to the Distilled Spirits Council of the United States. In part, they say, because “Americans are embracing the heritage of spirits products, and rye whiskey has a long heritage in the United States.”

“There are so many places that are making cocktails that are connected to our historic past,” says Derek Brown, spirits writer, D.C. bar owner, and the official spirits advisor to the National Archives.

In D.C., these throwbacks are not difficult to find: a moonshine list at Lincoln, sidecars served in apothecary bottles (acknowledging the cocktail’s original storage in decanters) at Dram & Grain, and apple toddies (to ease the common cold) at Copy Cat Co.

In an extreme example of this rooted inspiration, Brown created a cocktail with a historic basis as the “official cocktail” for the Spirited Republic exhibit. Working with with archivist Trevor Plante, he found an order from General Washington to the troops at Valley Forge, where after a long under-supplied, and difficult winter, Washington declares that congress has agreed to outfit the troops, and in addition grants “A gill of rum or whiskey [per] Man to be Issued to the troops to morrow.” Brown decided to blend those two traditional spirits—rum and rye whiskey—with a cherry bounce recipe used by Martha Washington (supplied from Mount Vernon’s distiller Steve Bashore), along with simple syrup, lemon juice, and soda water, to create the General’s Order Cocktail. (Get the recipe here!)

This sort of hearkening back to the past is what makes drinking today so special. “This is the best time for drinking in all of history,” says Brown. “The 19th century was when most of the greatest cocktails ever invented were made. Today we have all those drinks and we have bartenders taking these into consideration and transforming them into something completely different. They have technology and ingredients that they didn’t have in the 19th century.”

We imbibe about one third as much as we did in our historic heyday. (In large part, Brown thinks, because we know more about the health impact of alcohol now than we did in 1830.) In a way, we can thank our ancestors for doing a lot of our drinking for us. Now we know what we’re working with, so we’re able to drink less, but we’re able to really make that drinking count as more informed, inspired, and innovative alcohol appreciators.