Paris: City of Pearls

An exhibition at L’ÉCOLE, School of Jewelry Arts, explores the rise and fall of a remarkable trade that briefly made Paris the City of Pearls.

Tracing the lines on a 17th-century map of Arabia, the eye is drawn to a cluster of dots along the Persian Gulf and an alluring Latin inscription: “Baram Hic Magnum Copia Margaritarii”—here in Bahrain you can find many pearls. It is an annotation that highlights Europe’s long fascination with pearls, possibly the oldest known gem and one that has never gone out of fashion. By 1665, when this map was made, pearls were a well-established symbol of wealth and one of the most valued gems in the world. The reason was more than their natural iridescent beauty—it was also their rarity.

It's still not entirely understood what specifically triggers a pearl to form in an oyster, a mystery that only adds to their charm. Science has rejected the idea of a grain of sand—oysters have other mechanisms for dealing with such a common irritant. But some foreign body, possibly a parasite, finds its way into the oyster that then forms multiple layers of calcium carbonate around the intruder. Each layer is just one-thousandth of a millimeter thick, but over many months and years it develops into a pearl. Maybe one oyster in a hundred will form a pearl, and of these perhaps one pearl in a hundred is of high quality. With each differing in size, shape, and color—two identical, high quality pearls are exceptionally rare. And that makes them particularly precious.

The Persian Gulf is famous for its prolific oyster beds, and early occupants of the region probably treasured the pearls they found while foraging for food and materials. Certainly, by the time of the Roman Empire, pearls were a revered status symbol: Cleopatra supposedly dissolved and drank a near-priceless pearl to demonstrate her wealth. In medieval Europe, pearls were considered a lucky talisman incorporated into royal regalia: Queen Elizabeth I had some 3,000 pearl-adorned gowns. The obsession continued through the Renaissance and into the 19th century, when pearls were respected for being less ostentatious than other gems. The rarity of finding pearls of the same shape and light for jewelry made them very expensive.

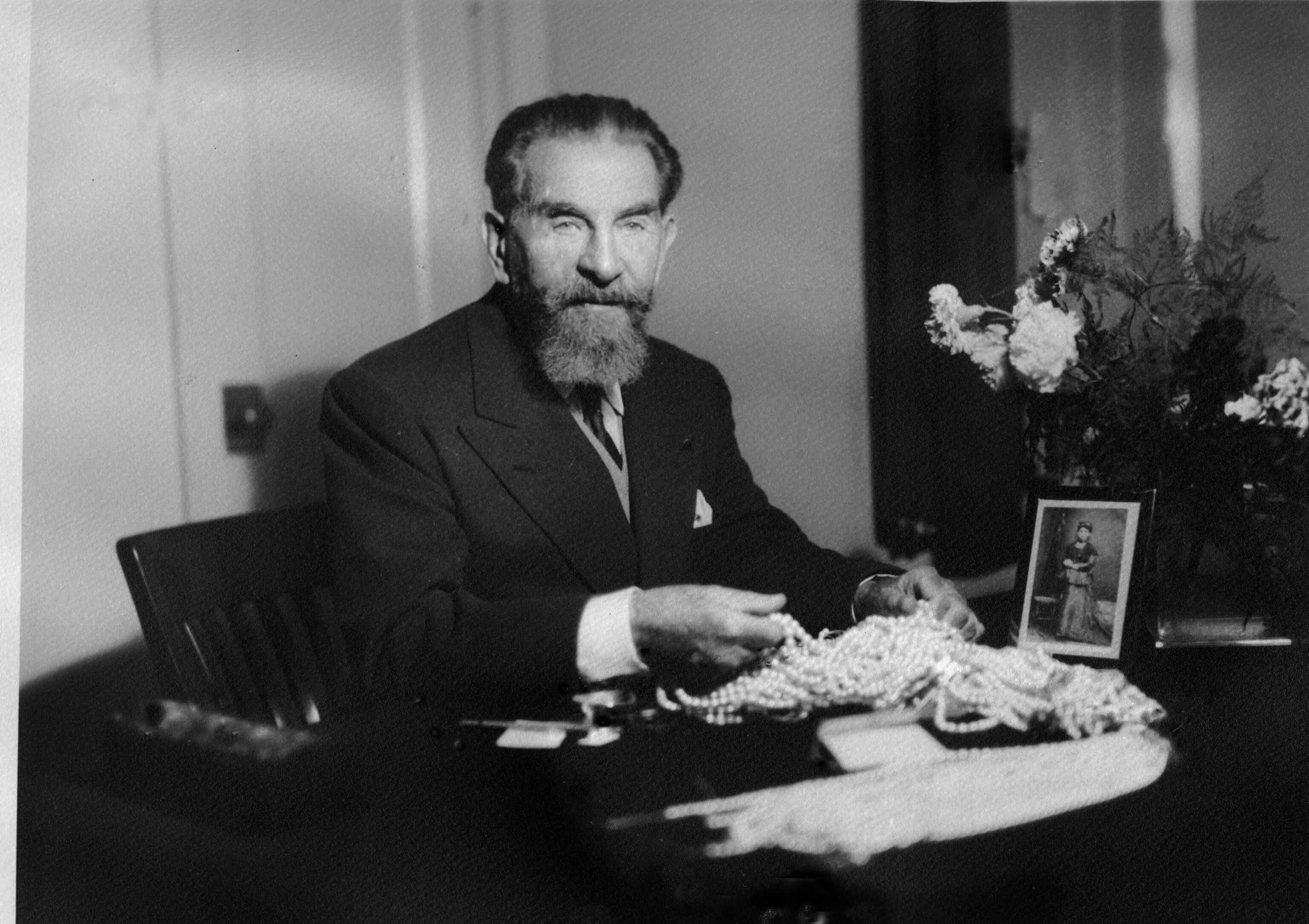

At the turn of the 20th century, French jewelers were anxious to acquire the best Arabian pearls to incorporate into their most spectacular designs. From behind the tall windows of Rue La Fayette in the Parisian jewelry district, they looked with envy at Britain’s domination of the pearl trade. The Persian Gulf, the world’s main source of pearls, was under British protection with its bounty going first to British controlled India and then to London: Parisian jewelers had to compete for the overpriced leftovers. But then things changed. Around 1904 to 1906, an Anglo-Indian economic crisis stemmed the flow of pearls for two years, leaving the Gulf’s pearl dealers desperate for money. Into this turmoil came an opportunistic French businessman: Léonard Rosenthal.

Having risen from poverty to become one of the top pearl dealers in Paris, Rosenthal was an adventurer with an eye for opportunity. In 1906, he travelled to the Persian Gulf, no easy journey, and in a brilliantly theatrical move exchanged his currency for small coins—arriving to trade with bags literally bulging with cash. To the cash-starved local pearl merchants, Rosenthal appeared as a savior. Dealing with them directly, he cut out the middlemen and offered higher prices than any potential competitor, securing his position as a preferred buyer. Year after year Rosenthal would arrive, buy Arabia’s pearls, and send them to Paris.

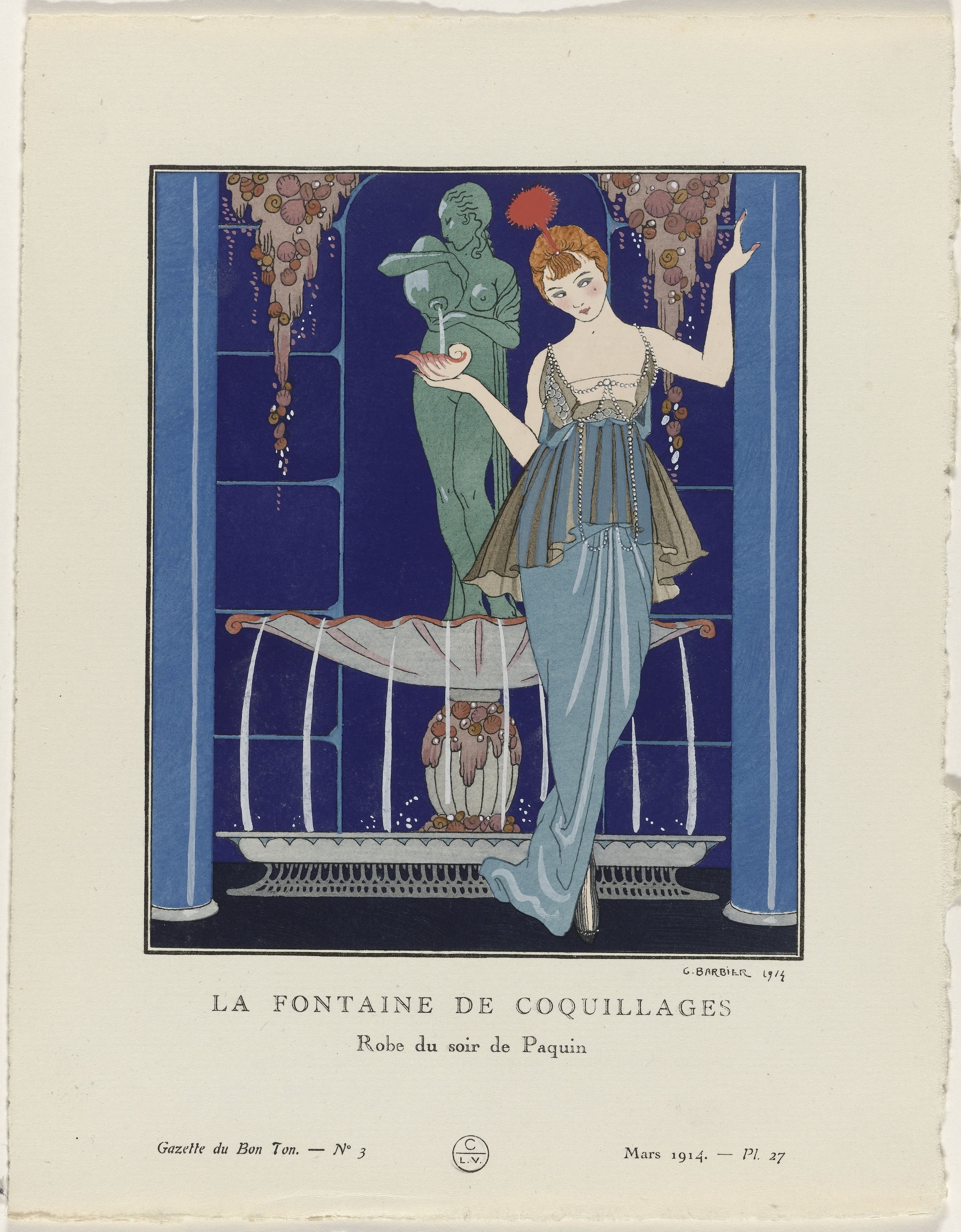

Pearlmania soon gripped the French capital. As pearls flowed into Paris, their influence extended beyond jewelry to become embedded in the city’s culture: Pearls appeared everywhere, on posters, in magazines, in advertising, in music, cinema, and, of course, they were prominent in fashion. Parisian jewelers built their designs around particular pearls, often acquiring the gems with the longer-term goal of assembling a rare string of matching pearls that would be worth a fortune. The trade’s success was epitomized by Rosenthal’s own achievements: In 1915 his workshops were producing 100 pearl necklaces a day and in the 1920s he was one of 300 pearl dealers on Rue La Fayette alone. Paris was the City of Pearls.

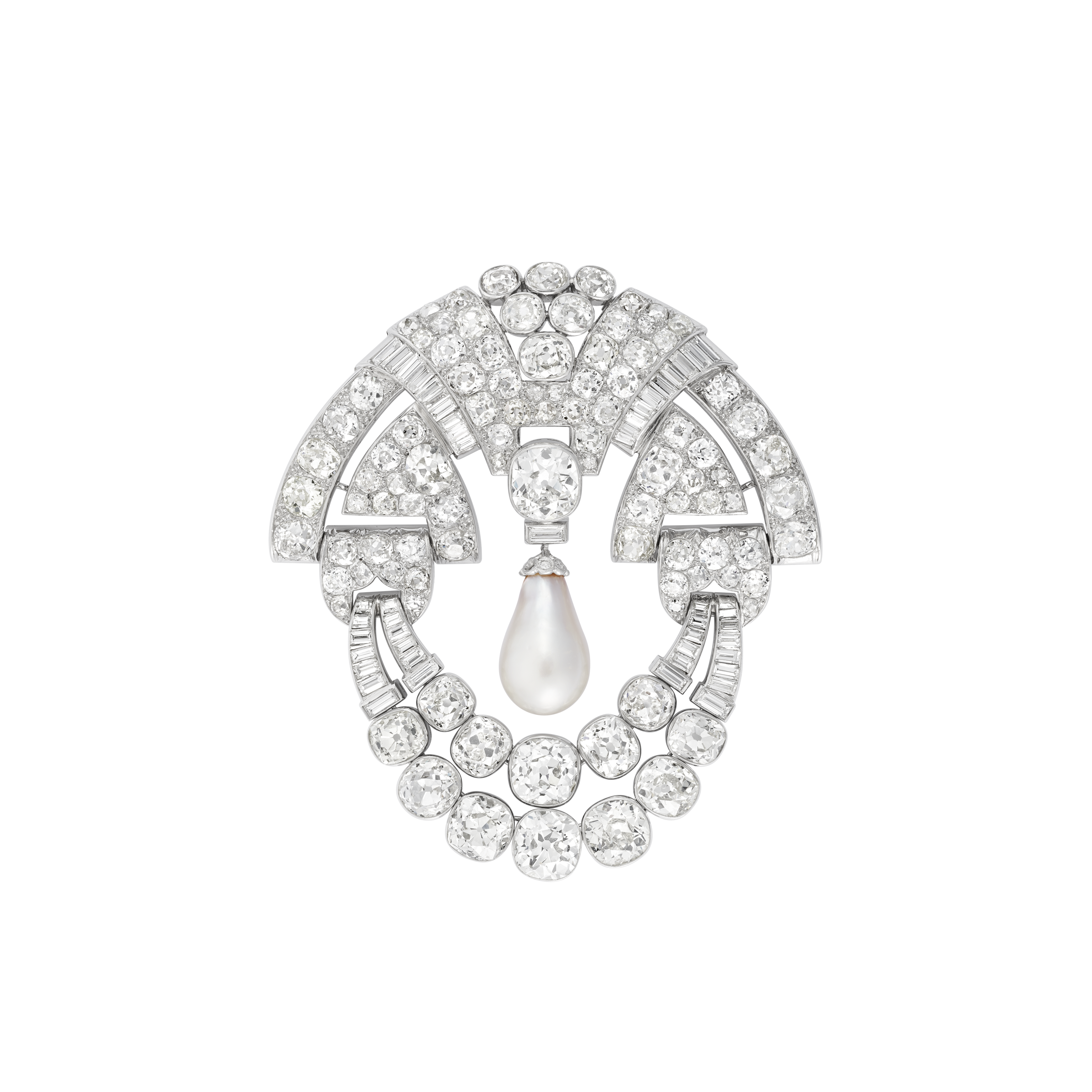

This pearlmania was reflected in the distinctive jewelry of two major artistic movements. The curving lines and organic forms of Art Nouveau relished the pearl for its imperfections, its irregularity echoing the eccentricity of Mother Nature. In contrast, the sharp-edged industrial styles of 1920s Art Deco saw jewelers seeking symmetry, geometry, and sheer quantity. Hundreds of pearls were painstakingly matched into strings of bracelets, necklaces, and sautoirs worn by the wealthy and nonchalantly draped across the body by women reveling in emancipation. Throughout these decades, Paris’s pearls remained most jewelers’ preferred gem, forming the centerpiece of their designs.

But as quickly as it had emerged, Paris as the City of Pearls was destined for an abrupt end. In 1925, the arrival of cultured pearls from Japan alarmed jewelers. Indistinguishable from natural pearls, these bigger, more uniform, and cheaper ‘man-made’ gems threatened to collapse the market’s value. Then, in 1929, the Wall Street Crash and Great Depression wiped out much of the wealth that previously could afford to buy natural pearls. Despite this, the Paris trade struggled on until 1939, when the Nazi occupation forced many Parisian gem dealers and jewelers to flee abroad. Among these emigrés was Léonard Rosenthal, who set up a new business in America—based on farming cultured pearls in Tahiti.

The rise and fall of Paris’s pearl trade is a story brought to life in a free exhibition at L’ÉCOLE, School of Jewelry Arts, in the French capital. Founded in 2012 with the support of French jewelry maison, Van Cleef & Arpels, L’ÉCOLE’s mission is to share jewelry culture with a global audience through free courses, talks, and exhibitions open to the public—Paris, City of Pearls is one of four exhibitions at L’ÉCOLE campuses around the world.

In Hong Kong, Shakudo: From Samurai to Jewelry explores the distinctive materials and designs that emerged from the repurposing of samurai sword fittings after the warrior class was abolished. In Shanghai, Designing Jewels looks at the rarely seen drawings that underpin every piece of jewelry as the first step in bringing it to creation. And in Dubai, Men’s Rings, Yves Gastou Collection, describes the evolution of men’s rings from a symbol of union to a distinctive artform through the unprecedented collection of antique art dealer, Yves Gastou.

These exhibitions, supported by Van Cleef & Arpels, shine a light on some of the fascinating but forgotten aspects of jewelry in art history—including the brief but brilliant few decades when Paris was the City of Pearls.

To find out more about the Paris, City of Pearls exhibition, click here.