Excerpt: Rare World War II maps reveal Japan's Pearl Harbor strategy

On December 7, 1941, Japanese forces attacked Pearl Harbor. Maps, both historic and newly created by National Geographic, yield new insights into the full scope of Japan's battle plans for the day "which will live in infamy."

When Germany invaded Russia in late June 1941, Japanese leaders debated whether to join their Axis ally and attack the Soviets—who had defeated Japanese troops along the northern border of Manchukuo in 1939—or proceed with plans to target European colonies in the Far East. They did not rule out invading Russia if the German advance on Moscow succeeded, but they saw more to be gained by seizing those Asian colonies and their resources, which they hoped to use to subdue China and sustain a vast empire they called the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. French Indochina and the Dutch East Indies were fairly easy targets, but the British would not yield Malaya and Burma without a fight, and their American allies would have to be dealt with as well. On July 2, Tokyo authorized “preparations for war with Great Britain and the United States.”

Japan's Best-laid Plans

After Japan took all of Indochina in late July and was subjected to an American oil embargo, Emperor Hirohito asked Prime Minister Hideki Tojo—a general committed to imperial expansion—to make one last effort to avert war. Talks in Washington faltered after deciphered cables from Tokyo indicated that Japan would attack if a deal was not reached by November 30. President Franklin Roosevelt declined to make concessions under the gun. On December 1, Admiral Yamamoto gave aircraft carriers the go-ahead to bomb Pearl Harbor—one of several blows delivered simultaneously in a vast Japanese offensive that expanded World War II enormously.

Path to War

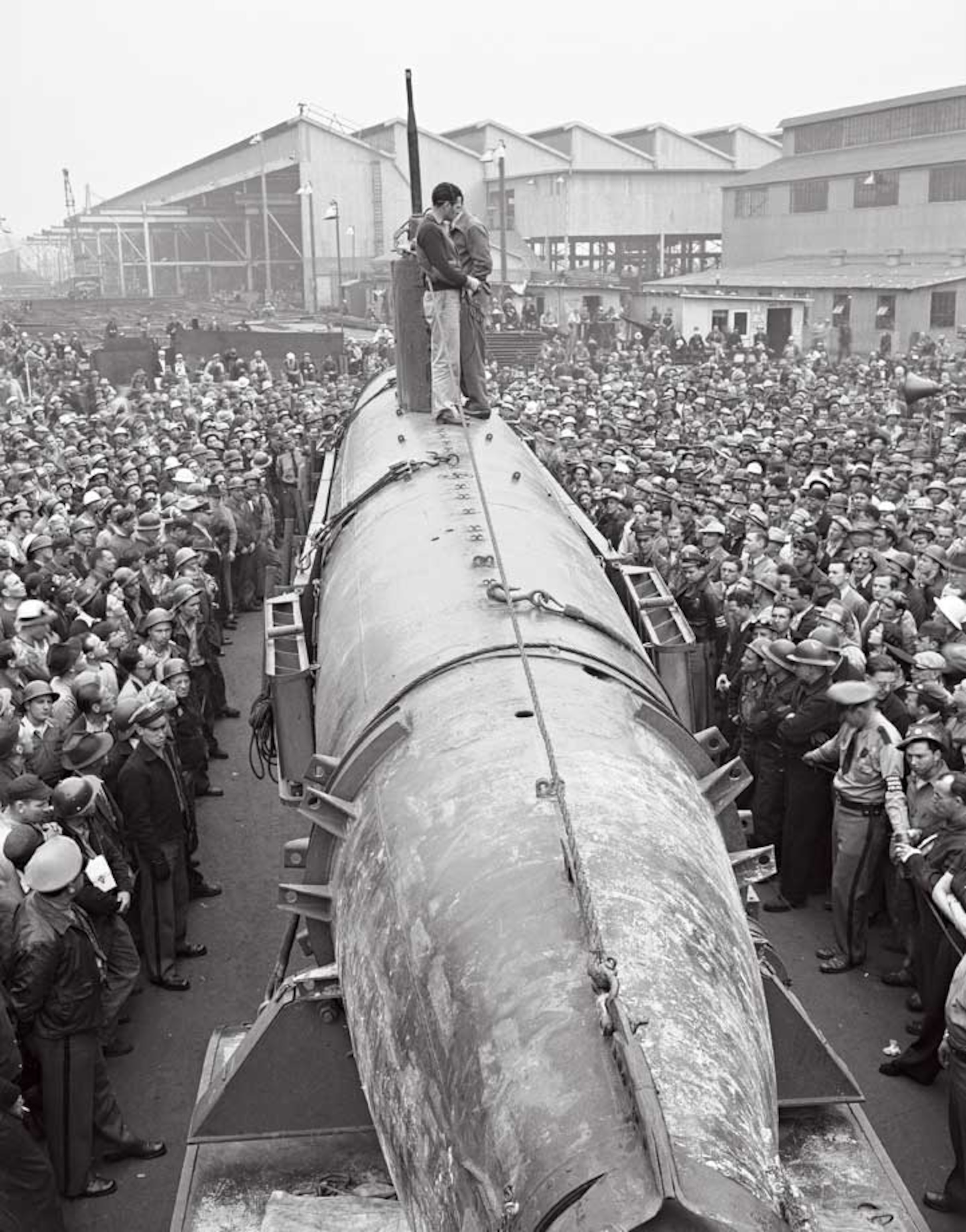

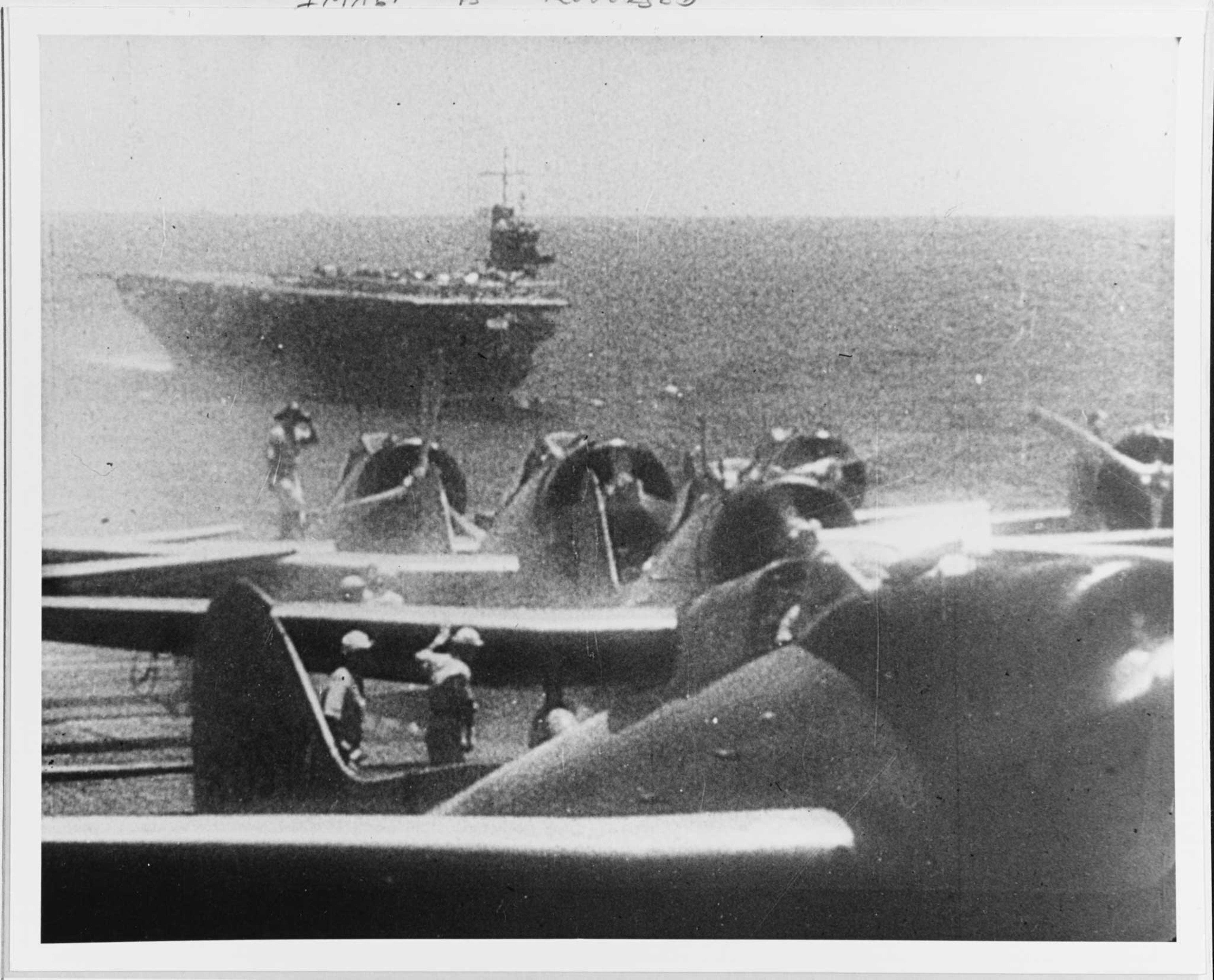

No nation invested more in naval air power before World War II than Japan. Admiral Yamamoto drew heavily on that investment when he assigned six big aircraft carriers of Vice Adm. Chuichi Nagumo’s Mobile Force to launch more than 400 warplanes of the First Air Fleet against Pearl Harbor. Shielded by battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and submarines, the carriers were dispatched by Yamamoto on November 26 as peace talks in Washington were breaking down. Five days later Emperor Hirohito authorized war on the United States, and Yamamoto sent Nagumo a coded message to proceed with the attack: “Climb Mount Niitaka.”

To avoid detection, the carrier task force observed radio silence and followed a northerly path to Hawaii, a route that was little traveled and subject to winter storms, which thwarted aerial reconnaissance.

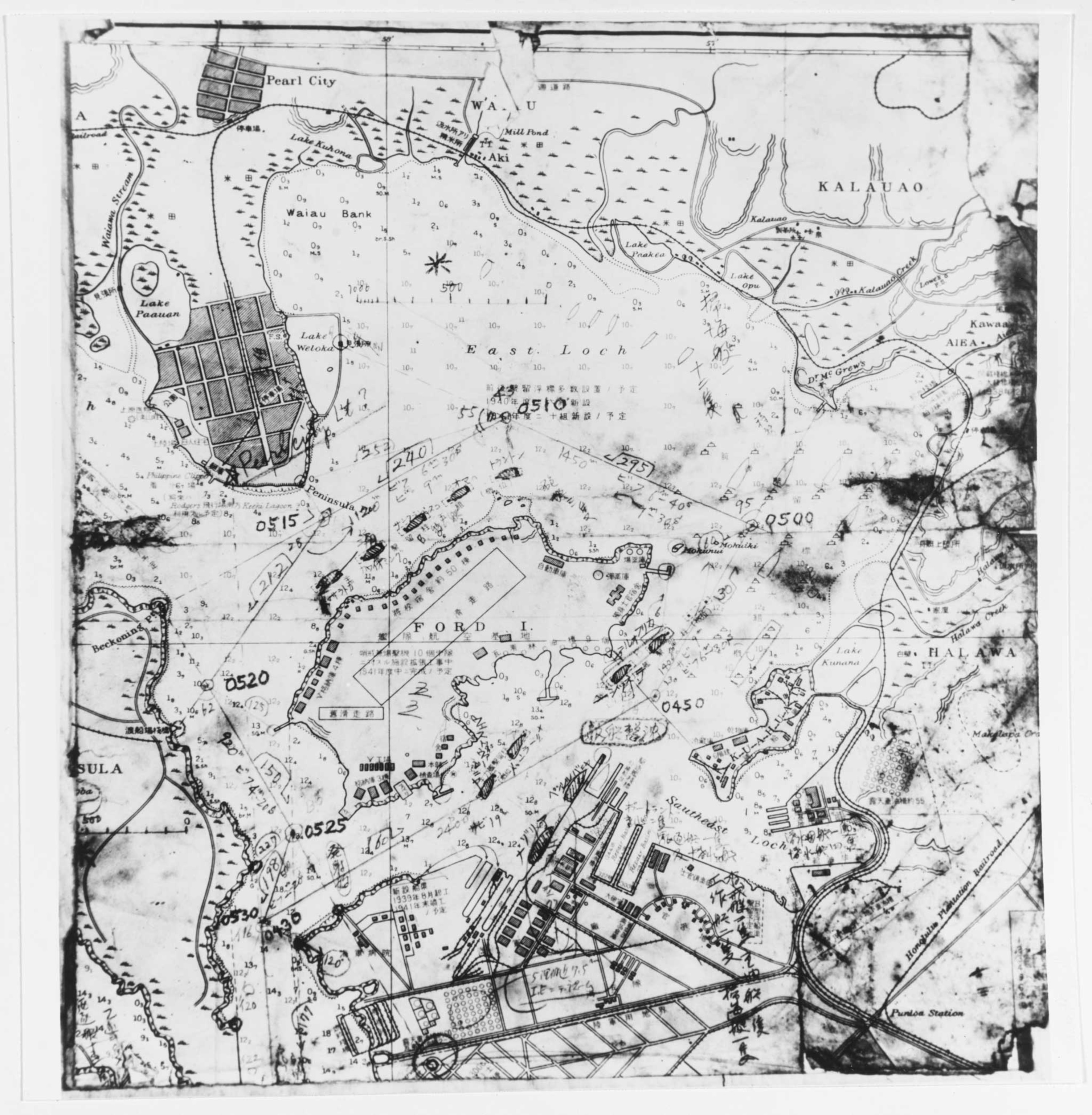

As indicated by the Japanese map below, showing Pearl Harbor in detail at lower left, that target was well charted by 1941. Intelligence on ships in the harbor and nearby air bases was provided by spies, notably Takeo Yoshikawa, a naval officer attached to the Japanese consulate in Honolulu who spied on the Pacific Fleet.

At dawn on Sunday, December 7, the carriers turned into the wind to launch their planes amid heavy swells. “The carriers were rolling considerably, pitching and yawing,” remarked Tokuji Iizuka, the pilot of an Aichi 99 dive-bomber on the I.J.N. Akagi, Nagumo’s flagship. When planes left the flight deck, he added, they “would sink out of sight” before bobbing up and ascending through the clouds. Iizuka took off with the second wave of attackers around 7 A.M. Not until he reached Oahu two hours later did the clouds break and allow him a breathtaking view of Pearl Harbor in the distance, wreathed in smoke as bombs dropped by the first wave shattered the peace.

Assault on Pearl Harbor

The surprise attack on December 7 was not entirely unforeseen. Chiefs in Washington knew that Japan would soon wage war, and commanders at Pearl Harbor and elsewhere in the Pacific were warned that hostile action was “possible at any moment.” But officers informed of the threat doubted that an attack would occur as far from Japan as Pearl Harbor. They knew the Philippine islands were vulnerable to assault but thought the outer limits of any Japanese offensive would be U.S. bases on Guam, Wake Island, or Midway, situated 1,300 miles closer to Japan than Oahu. Two aircraft carriers that Yamamoto hoped to attack at Pearl Harbor, U.S.S. Enterprise and U.S.S. Lexington, were away on the 7th because they had been sent to deliver warplanes to Midway and Wake Island. Pearl Harbor was not on high alert.

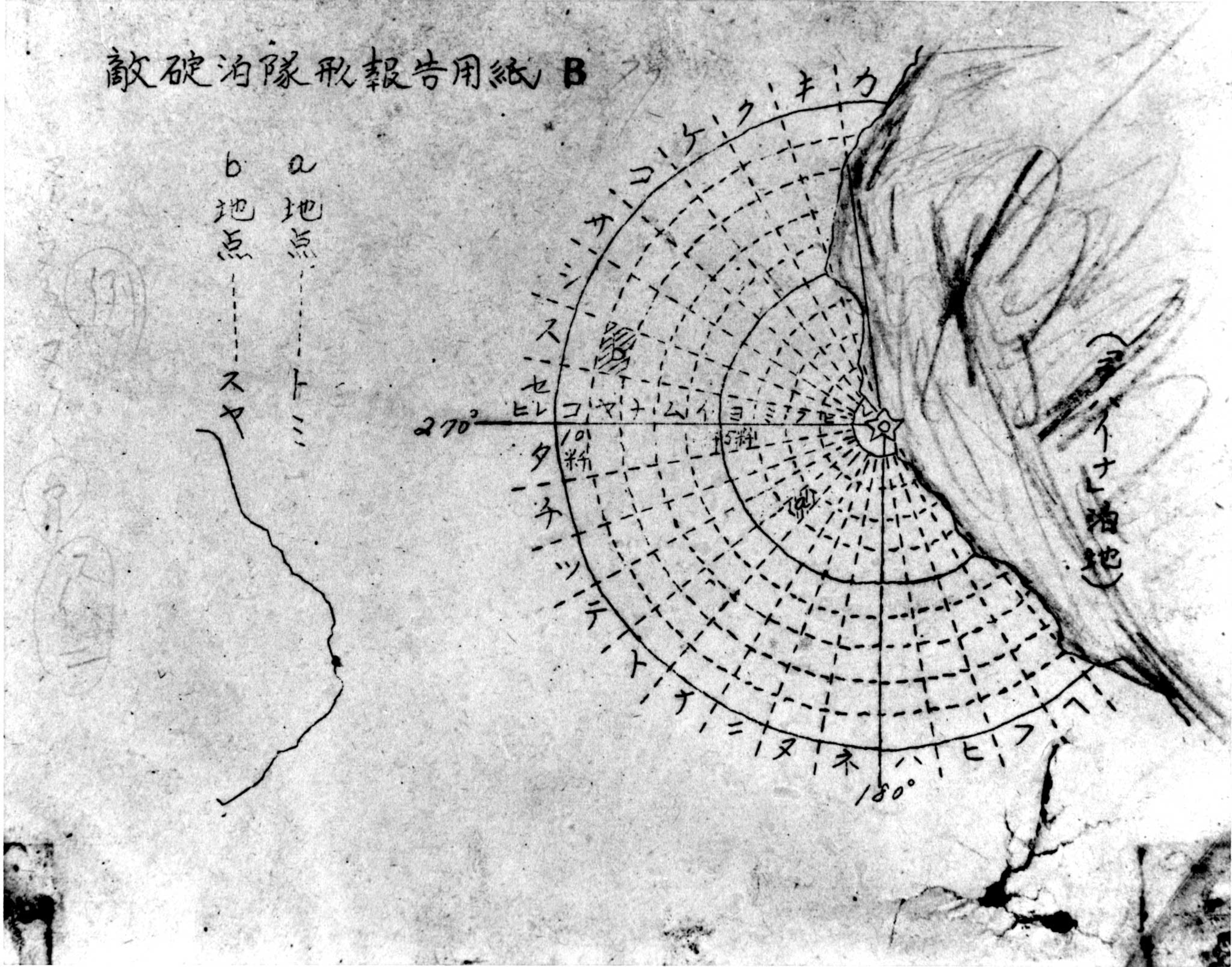

As shown below in a map retracing the assault in Tokyo time, the first wave of Japanese fighters and bombers came in from the north and were ordered to attack by Cmdr. Mitsuo Fuchida at 7:49 A.M. Hawaii time. Their objectives included airfields on Oahu, including Hickam Field near Pearl Harbor and Ford Island amid that harbor. But their prime targets were the warships moored there.

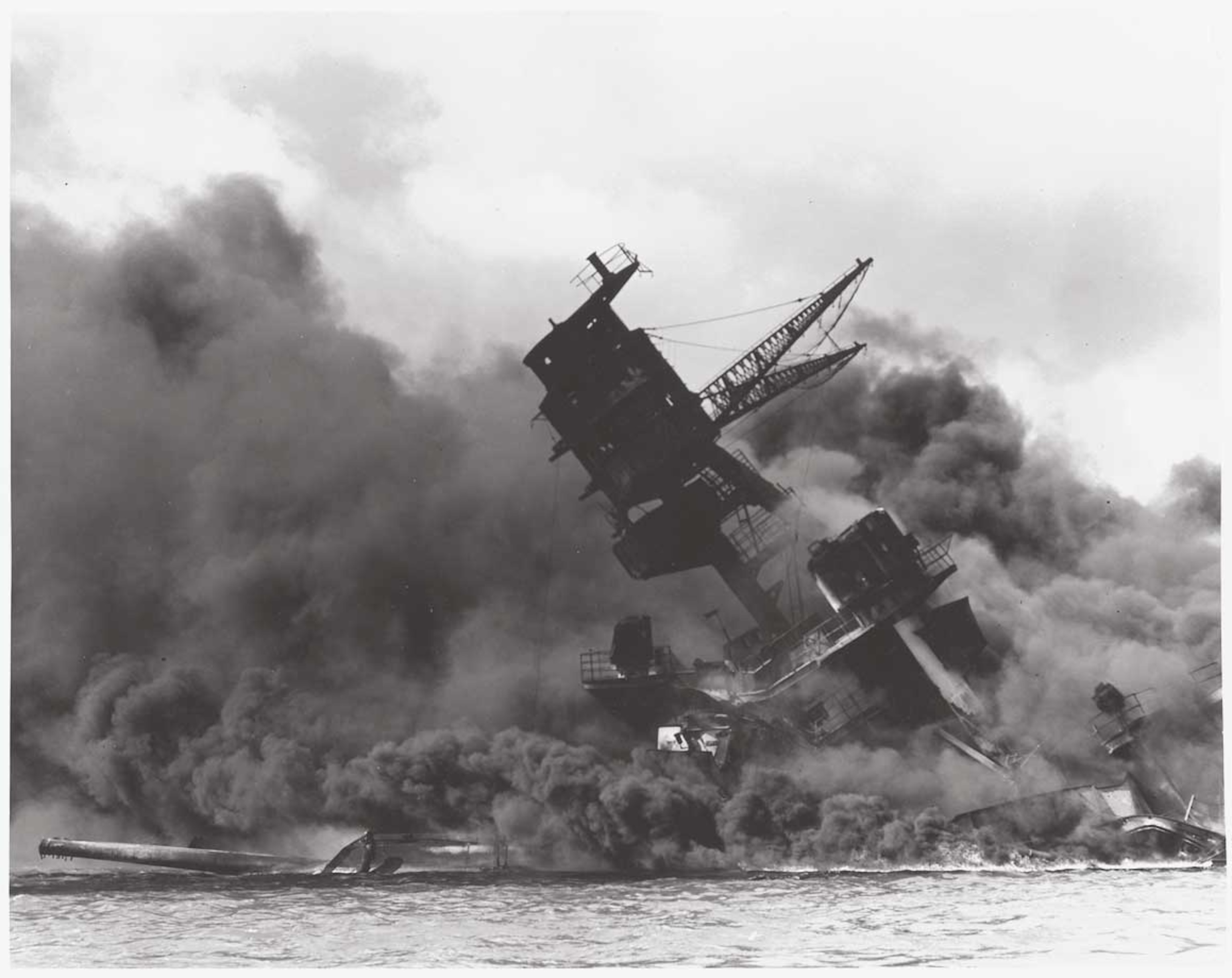

Some planes came in low and released torpedoes, one of which struck the battleship U.S.S. Oklahoma and caused it to capsize. A bomb dropped at high level on the battleship U.S.S. Arizona penetrated its magazine and triggered a catastrophic explosion. Around 9 A.M., the second wave of war-planes came in and added to the carnage. Within a few hours, the attackers sank or badly damaged all eight battleships at Pearl Harbor and 11 other warships, destroyed 170 aircraft, and killed or wounded more than 3,500 Americans.

As shocking as this assault was, the enormity of the offensive was even more stunning. On that same day, Guam, Wake Island, and the Philippines came under attack, and Japanese troops invaded neutral Thailand and British-ruled Hong Kong and Malaya. The Pacific Fleet dodged a bullet, however, when the fuel depots and repair yards it relied on emerged largely intact.

Winston Churchill had no doubt that America would rebound from the attack and cheered its entry into the war on December 8. “Today we are all in the same boat with you,” Roosevelt cabled Churchill, who trusted that Britain’s alliance with the U.S. and the Soviet Union would ultimately sink the Axis.