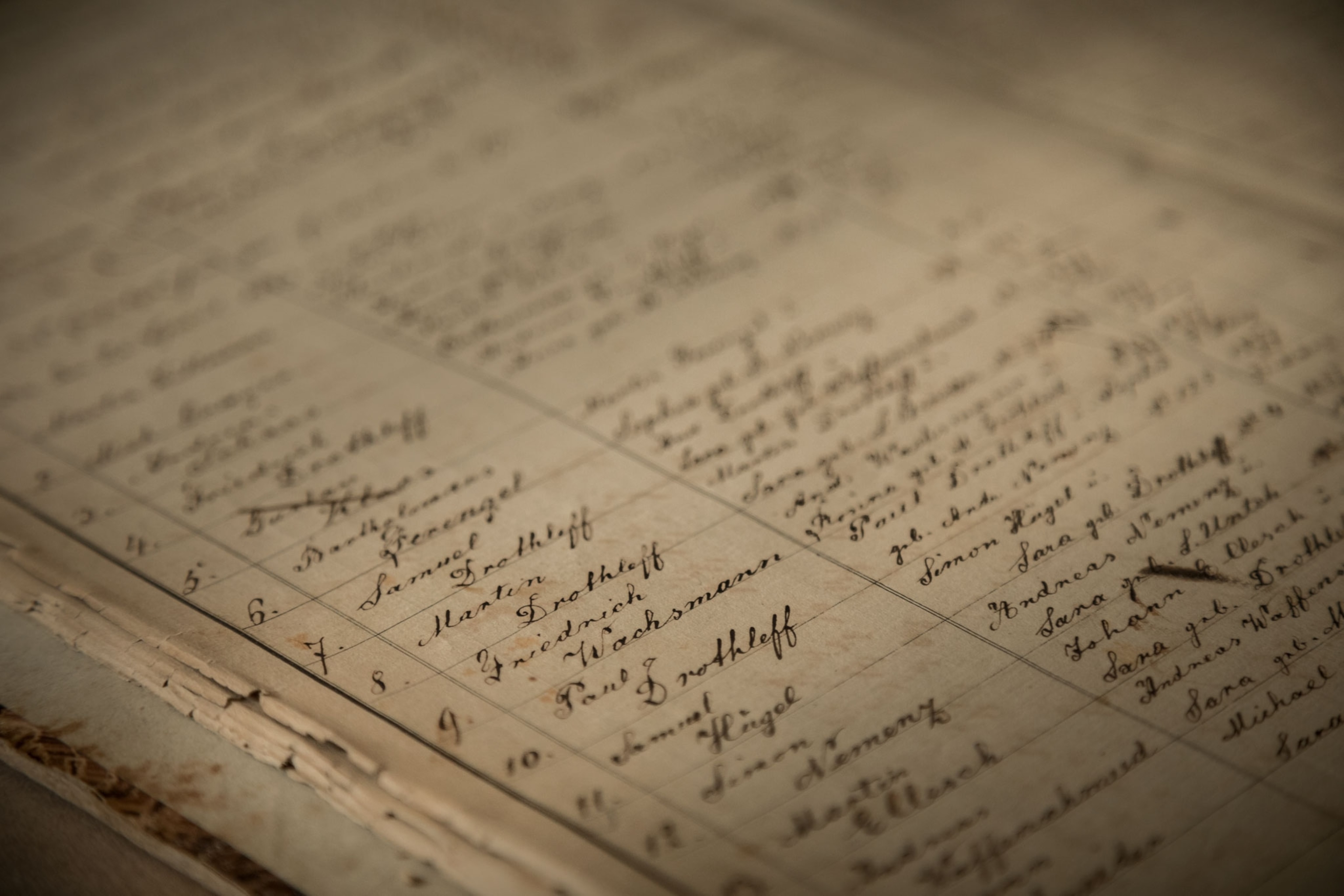

Susanna Riemesch-Wachsmann was the last Transylvania Saxon to be married in her home village of Richiș, Romania. That’s where she first met her husband Udo. He lived outside the country so the young couple could only see each other during holidays when he came to visit the motherland.

After a four year courtship, they got married in 1990. “On the Wednesday before my wedding, the preparations began,” she recalls. “The whole community gathered to help make the food. We cooked and baked in the parish hall until Saturday morning. It was then time for the church service. When the choir sang, the whole congregation joined in. We continued celebrating until the next day. And after that everyone stayed to clean up, which took another two days! Even now, when I think back to it, I can feel the strong sense of belonging I felt at the time.”

The newlyweds didn’t stay in Richiș, though. Like many Transylvanian Saxons, a minority group who can trace back their ties to the mountainous region to the 12th century, they moved away hoping to escape the hostilities they’d faced since the end of World War II. “Everything was so different, so big, so loud, so cold,” remembers Riemesch-Wachsmannn. “I was homesick. I still have a foot in both worlds. My house is here in Germany and I have everything I need: my family, a job, friends and hobbies. But, I’m at home in Richiș.”

When photographer Davide Bertuccio met the Riemesch-Wachsmann family in April 2017, he was looking for stories that could speak to the impact of globalization and modern life on small ethnic communities. What he found was much more layered. By documenting the family’s summer visits to the region, comparing it with their daily life in Germany and looking through their personal photo albums, he began to unravel the complex history of a people whose fate has always been inextricably tied to the changes that continue to take place in Europe. (See photographs of Transylvania's farmers.)

Though originally from the Rhein basin in Western Germany, labeling them as Germans living in Romania is reductive and misleading, says Francesco Magno, a doctoral student in Contemporary History of Central and Eastern Europe at the University of Trento. His research focuses on ethnic relations in Transylvania. “When Saxons arrived in Transylvania nine centuries ago, Germany was a kaleidoscope of regional powers that were extremely unconnected to one another. At the time, the idea of a united German nation as we understand it today did not exist,” he says. The Saxons, mostly craftsmen and well-off peasants, brought their own culture and dialect to the Romanian hillsides, developing over time distinctions influenced by their surroundings that further distanced them from modern-day Germany.

Yet, despite living in largely remote and rural communities, surrounded by the Carpathian and Apuseni mountains, they were not immune to the upheavals that transformed Europe throughout the last century. “In the thirties many Saxons were attracted by the Nazi idea of ‘Germanness’ that extended beyond the political borders of Germany. It was the first time that they felt a connection with that country,” observes Magno. Some fought alongside Hitler’s forces. When World War II came to an end, the Saxons, largely seen by the Soviets as collaborators, were arrested and sent to labor camps in Siberia and Ukraine. Those who remained had to face the Communist regime of Nicolae Ceaușescu from the mid-1970s to the end of the 1980s. The dictator, who dreamed of an homogenous Romania, expropriated many Saxons, encouraging them to seek refuge in neighboring states.