War in Syria: Stories of Survival and Hope

A reporter follows a group of Syrians from all sides of the war—fighters, students, children—and their struggles to survive the conflict.

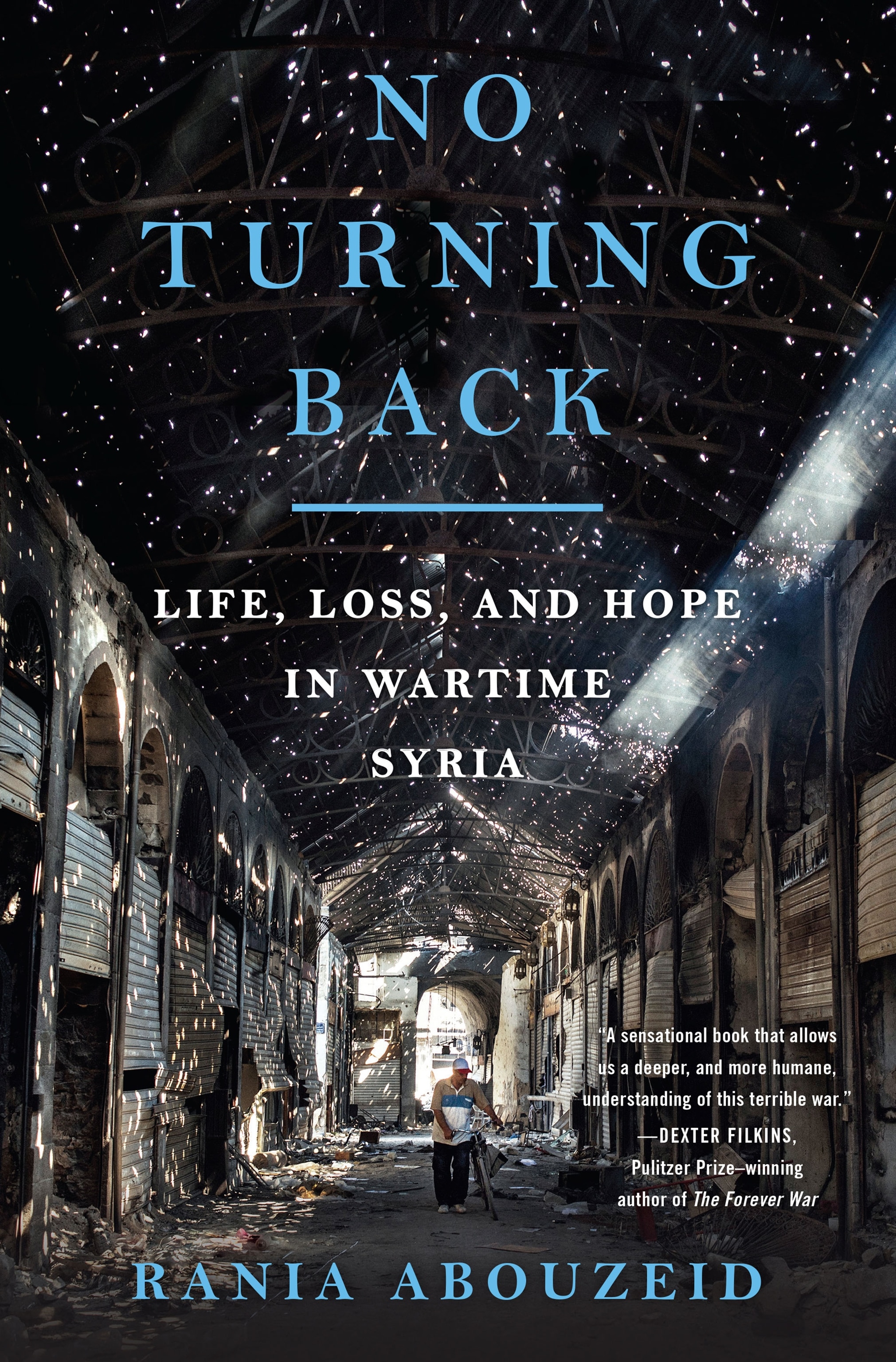

“War arrives suddenly, uninvited, and brings with it a new normal,” writes Rania Abouzeid in No Turning Back, her poignant account of the Syrian conflict. Following the lives of a group of people from rebel-held areas over a period of five years, she brings home to us what television coverage rarely can: the human dimension of one of the most violent and complicated conflicts since World War II.

Speaking from her U.K. publisher’s office in London, she explains how children learn the vocabulary, and sounds, of war; how the CIA armed rebel groups and used them to spy on jihadists; and why she believes the West should be providing more humanitarian aid to Syrians.

Your book brings to life the experiences over five years of a group of characters caught up in the Syrian conflict. Tell us a bit about your own background, as well as the dangers and other impediments you faced in your reporting.

I’ve been covering the Middle East and Southeast Asia for over 15 years, including a number of different conflicts. I covered the Tunisia uprising, the Egyptian Revolution, and made my way to Damascus in late February 2011 to get an idea of how the Syrian capital was responding to the momentous events that were happening. I witnessed one of the first protests, outside the Libyan Embassy, which was one of the biggest and earliest attempts by Syrians to push the boundaries in a state that had been governed by an emergency law since the 1960s. From that moment, I focused on Syria.

I knew that whatever was going to happen there would affect the whole Middle East.

I learned in the summer of 2011 that I was blacklisted by Damascus, but not as a journalist. They considered me a spy working for several foreign states. I was wanted by three of the four main intelligence agencies and banned from entering the country. That forced me to focus on the rebel side, which meant being smuggled across the Turkish border into northern Syria. I did that for years, and even though I was banned by Damascus I managed to make two trips, one in 2013 and one in 2016, to government-held parts of Syria. It wasn’t easy. It’s a very vicious war, so it was a difficult story to report.

The United States lists the Nusra Front as a terrorist organization. Yet you eschew any political or ethical judgement in your portrait of one of its fighters, Mohammad. Don’t you worry that by being sympathetic you are giving this brutal group a valuable propaganda coup?

I am not being sympathetic, I am not being judgmental, I am just presenting the information and leaving it up to the readers. My goal is not to characterize, demonize, patronize, or glorify anybody. My interest is to understand. I want to understand a person’s motivations, their worldview, and see what makes them tick. I believe very strongly in the intelligence of the readers. You don’t need to bang them over the head with how terrible a person might be, because it’s evident from their actions.

Mohammad is a man who was radicalized at an early age and spent a number of stints in prison, which only served to further radicalize him. In 2011, he saw an opportunity to take revenge against the regime of Bashar al-Assad. He worked to push what was a peaceful revolution in a very different direction, along with other like-minded men.

In following his story and three al Qaeda characters, you see how the revolution was Islamized and the roles that organizations like al Qaeda played on the battlefield and also politically. Mohammad committed war crimes that he admits to, and is proud of. But it’s not about me liking or disliking; it’s about presenting information.

At one point, one of the people you write about, Ruha, says, “We were fated to learn about things children shouldn’t learn about.” Introduce us to this brave little girl, and tell us about the new vocabulary she learned.

Ruha was nine years old in 2011. The first time the reader sees her, she is opening the door to a dawn military raid on her family home because they’re looking for her father, who was a protestor. She’s a very precocious young girl who was absorbing what was happening around her, even though her parents tried to hide things from her. But they couldn’t. Children very quickly learned and this was reflected in the games they played and the terminology they came to understand. For example, they learned what a mortar sounds like or the difference between a sniper’s bullet and an anti-aircraft gun. The local version of cops and robbers became revolutionaries versus regime thugs. They also started incorporating the language they were hearing into their games and activities.

Ruha then became a refugee. She and her family escaped from Syria because her youngest sister, three-year-old Tarla, had an odd hormonal problem, which the few doctors left in town told her parents was brought about by fear. There were no specialists in their area so they escaped to seek medical treatment.

Another of your main characters, Suleiman, was from a good, middle-class family, wasn’t he? Explain how he gets sucked into the conflict and his, and other rebels’, use of social media.

Suleiman was a privileged young man who had things most young men want. He had a good job, a lot of money, and came from a family that had connections to the regime. He was also aware of his privilege and when the revolution started, in March 2011, Suleiman took to the streets because he felt that others deserved these same opportunities that he had. So he became a civil activist, documenting the weekly protests in his hometown using his smartphone and uploading them to social media, the same way that many thousands of Syrians did, to try and show the world what was happening in their homeland.

The U.S. fully entered the conflict in 2013. Tell us about Timber Sycamore and the espionage work of the Hazm militia.

The U.S. had been there from the beginning, but not in a leading role. Timber Sycamore was the code name for the CIA effort to arm the rebels, which came into being in late 2013. One of the first rebel groups to be vetted by the CIA was a group called the Hazm Movement and I outline, for the first time, in this book some of the group’s clandestine work.

Hazm was one of the many rebel groups operating in Northern Syria. It had formed from the remnants of a much bigger group called the Farouq Brigades. That group splintered and from those splinters emerged the Hazm Movement. They were non-Jihadist and advocated a civil state in Syria. The espionage involved mapping out the foreign fighters and trying to find out who they were and what they were up to, because their idea for a future Syria didn’t match Hazm’s.

We can’t talk about Syria without talking about ISIS. Tell us about Bandar’s experience in Raqqa, capital of ISIS’s so-called caliphate.

Bandar is a university student in Homs when you first see him in the book. He was a roommate with one of my four main characters, a man called Abu Azzam, who ends up becoming a commander in the Farouq Battalions. Bandar didn’t want to participate in the protest. He disliked the regime of President Bashar al-Assad but feared retribution if he participated—not necessarily against himself, but against his family. He tried to stay away from the initial protests, even though his brother had picked up a gun and fought alongside his roommate Abu Azzam. Bandar watched it from a distance initially. He was from Eastern Syria, near Raqqa, so after Homs fell, he moved to Raqqa and watched the black flags come up and how the city, which was one of his adopted hometowns, changed in ways that both terrified and disgusted him.

Your book ends on a redemptive note. Was that important to you?

I put hope in the subtitle because some of the people in the book haven’t given up hope. They’re still struggling and trying to rebuild their communities, as well as their lives. It was important to show that, even in the grimmest, darkest, bloodiest wars, there are still people who just want to live, and fight for that right, and cling to the things are singular to their culture and identity, like where they’re from, their families, their dreams. These are the building blocks of the communities. Every life is consequential because it’s part of the mosaic of society. That’s true when that mosaic is unravelling; but it also works when that mosaic is being woven back together again.

I want readers to experience the book the way the characters experienced the realities on the ground. I want to place readers there, to give them a sense of what it was like for the people who were living it. They’re all real people, there are no composite characters, and they went through things that most of us, if we’re lucky, can’t even imagine. I want to covey that with as much immediacy as I can.

The conflict in Syria has claimed the lives of an estimated 500,000 people and seen more than 5.5 million flee the country. Do you see any hope that the civil war will be resolved any time soon?

All civil conflicts eventually end. The question is: When and how many more people have to die until you get to that end point? The Syrian conflict is no longer solely about Syrians. It’s a complicated, international battlefield with Russians, Americans, Turks, and Saudis, the Gulf states and Iranians. The outcome has more or less been decided, in the sense that Assad is not going anywhere. He has no reason to negotiate his own demise, especially as he’s making gains on the battlefield, thanks to his allies. But the war is by no means over. Syria is a very fragmented state and it’ll still take many years to put it back together, in whatever form that eventually takes.

What more can the U.S. and other Western powers do?

That’s not a question for me to answer. I’m not on the opinion pages, and I try to stay off them. But the humanitarian need is massive, and it is woefully underfunded, whether inside Syria or for the refugees. It has been called the gravest humanitarian crisis since the end of World War II. Politics aside, just help on the humanitarian level. Start with that.

A portion of the earnings from No Turning Back will be given to Inara, a nonsectarian charity that provides medical care for children.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitteror at simonworrallauthor.com.