What the world can learn from West Virginia’s successful vaccine roll-out

In the race to vaccinate, the state's personal touch is a winner.

On an early February day, two nurses make their way up a steep dirt road, toward the top of what most locals know as Murder Mountain, to reach the home of Bonnie White. Here they will administer her first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine.

“I love you,” says White in a singsong voice when nurse Cristine Dean arrives.

“I love you, too. How are you doing?” Dean replies, setting down her medical bag.

White’s husband, Jerry, died almost two years ago. When he was alive, he would take every opportunity to joke around with Dean and her supervisor, Kimberly Becher, the doctor who runs the health clinic in Clay County. Because severe rheumatoid arthritis has largely immobilized White, Dean and Becher have been making regular home visits, driving nearly half an hour to get to where she lives.

But this visit was special. Dean and Jeremy Walker, a recently hired nurse, had been assigned to deliver the COVID-19 vaccine to home-bound patients. Immediately upon entering White’s home, they asked a series of questions to assess her health and determine whether she would be able to handle it.

Dean and Walker are administering the Moderna vaccine, each vial of which contains approximately 10 doses and expires six hours after being opened. The nurses have one vial that they opened four hours ago. Protocol requires that patients with a history of allergic reactions remain attended for 30 minutes after being vaccinated.

After a day spent speeding along the twisting roads that thread Clay County, Dean and Walker still have three more patients to visit. They aren’t going to be able to drive across the county, give the patients vaccines, and monitor their conditions before the doses in the vial expire.

Dean texts Becher to figure out what to do. Time is running out, but they arrive at a resolution.

At the next patient’s house, Dean gives the eighth and ninth vaccine doses to the patient, an elderly woman, and her husband, who wasn’t on the schedule. Then Walker calls a friend who has a lung condition. Dean prepares a syringe in the car, hops out after a long drive along Elk River, gives the man his shot, and heads back to the health clinic to figure out how to vaccinate the patients she was unable to visit.

It will all work out eventually. But on this day, no dose has been wasted.

This race against the clock is a common factor in the enormous national effort to distribute COVID-19 vaccines to people around the country. It is an effort at which West Virginia became an unlikely leader. In the first couple weeks of distribution, the state successfully administered nearly all of its allotted vaccine doses—the highest percentage in the country; now, West Virginia is among the top half dozen states with the greatest proportions of fully vaccinated residents.

This is unusual because people have grown accustomed to the state being “dead last,” says Lynne Fruth, who runs more than a dozen pharmacies in West Virginia. Dead last in what, exactly? “Everything,” she says.

West Virginia has struggled with high rates of poverty, food insecurity, drug addiction, and obesity (among other poor health conditions). The story of struggle, isolation, and rural poverty has become a dominant regional narrative. The state’s emergence as a leader in public health is surprising.

Trust in local doctors, nurses and pharmacists has helped the state get residents vaccinated.

This helps illustrate why West Virginia has been so successful in distributing the COVID-19 vaccine: The state has largely allowed local organizations and groups to lead vaccine distribution efforts in their respective regions. (West Virginia also relies on communities to provide food to the hungry.)

“Patients trust their medical home,” says Becher. “I had multiple patients tell me that they weren’t going to get [the vaccine] until I called them. I didn’t lay out the clinical trial data or even have to answer any questions; they agreed because I am their family doctor.”

On the logistical side, Becher says, “We know who needs the shot but might not have the means to register, or to physically come to us for it. We know who we need to reach out to, who otherwise might go unvaccinated.”

In other words, local doctors and health care providers already have the relationships necessary to get vaccines into arms.

In mid-December 2020, when states received their first vials of vaccine, West Virginia was the only one to opt out of the federal partnership with CVS and Walgreens to distribute doses to long-term care facilities. Instead, more than 250 local pharmacies, including Fruth’s, volunteered to bring the vaccine to long-term care facilities; within a couple of weeks each resident had been given the first dose of the vaccine. No other state was able to do the same as quickly. (This is what you can safely do after you're vaccinated.)

Since then, as the state moved to serve other members of the population—first responders, public health officials, home health aides, transportation workers, teachers—local health care providers have been given room to decide how best to get people vaccinated.

An insufficient early approach relied on just a handful of regional distribution centers that were far away from some of the poorest and most rural counties. When doctors complained of inefficiency, the state opened distribution centers in each of its 55 counties.

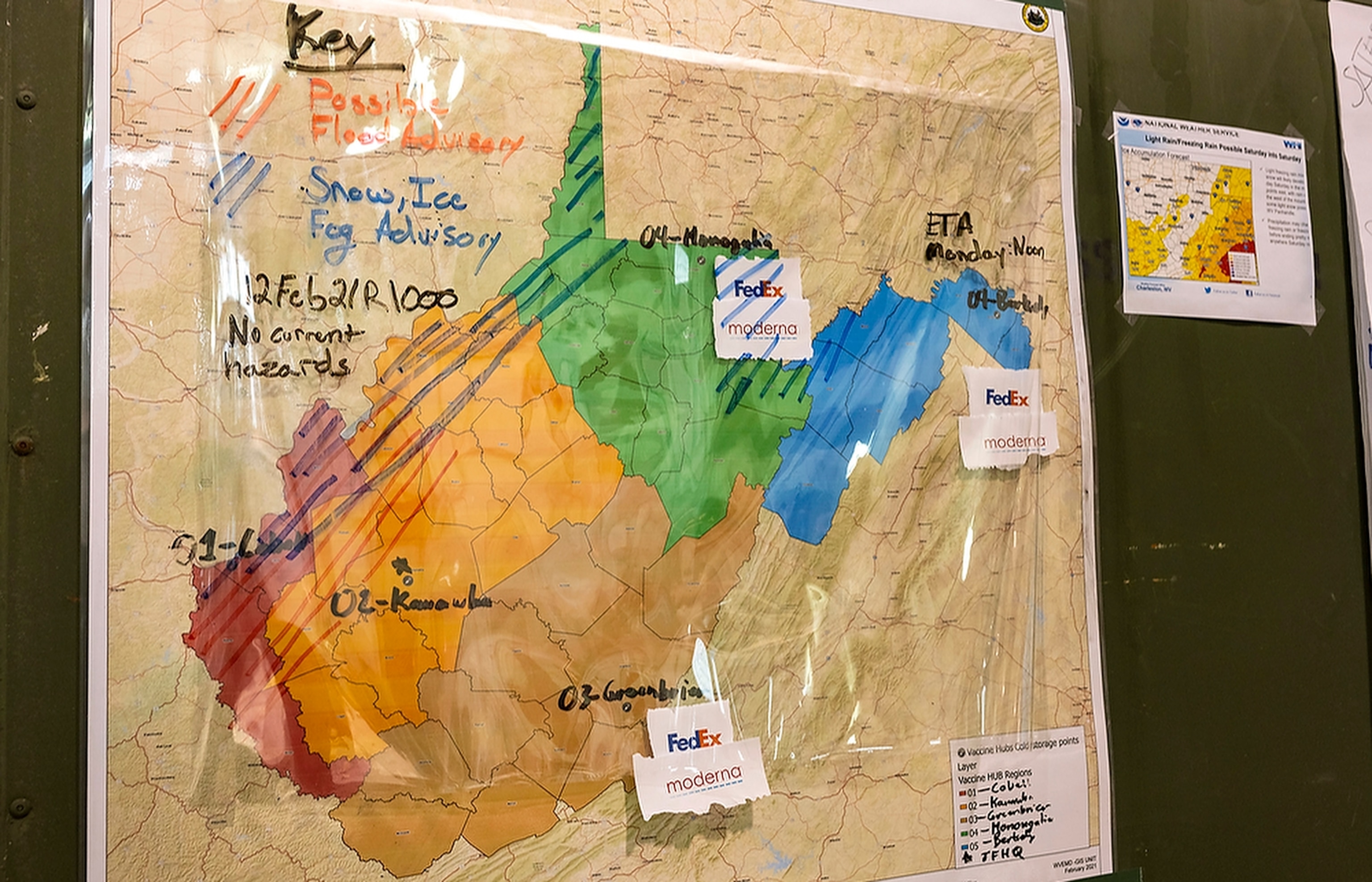

The day-to-day operations of the distribution centers—their structure, placement, and staffing—are left to locals. They’ve since slipped into what Sherri Ferrell, CEO of West Virginia Primary Care Association, calls a “battle rhythm.” Ferrell represents primary care providers on the West Virginia Joint Interagency Task Force for Vaccinations (JIATF), a group that serves as the logistical hub for the state’s COVID-19 vaccine distribution efforts. As West Virginia’s governor’s office and the CDC set goals and guidelines, the task force determined how counties would meet them. (Here's the latest on each COVID-19 vaccine.)

“As information is provided on how many doses are available to each county, it’s really about learning to get into that rhythm of planning,” Ferrell says. “We’re moving very rapidly, and it’s week to week. [But] the health departments, and health centers, this is what they do. We need to let them do what they do well.

Carrie Brainard, the threat preparedness coordinator for the Mid-Ohio Valley Health Department—West Virginia’s only regional health department—remembers sitting in meetings as logistics were first discussed

“The discussion was, ‘We need to do this. How are we going to do it?’” says Brainard.

Localities have adopted different strategies. In Roan, the hospital has taken the lead, hosting vaccine distribution events and managing most of the logistics, with support from others. In Wirt County, local clinics have hosted vaccination sites. In Pleasants County, the health department is in charge.

“We know we don’t have a lot of resources, so we don’t have time to play the turf game,” says Brainard. “We know that we need to rally together and work together."

In Clay County, Community Care of West Virginia, the health clinic Becher works for, has partnered with the school system to lead local vaccine distribution. On the same morning that Dean and Walker rush around the county to empty their vial of Moderna vaccine, Community Care held a distribution event at the local high school.

Debby Taylor, a teacher’s aide at Clay County Elementary School, walks in around 8:30 a.m.

But not every appointment goes smoothly. Even with the support of local health care providers, there is a lot of hesitancy—and fear—around getting the vaccine.

Another teacher from the elementary school enters, clutching her book bag and looking down at the floor. “So how are you?” Taylor asks

“I don’t know,” the teacher responds before bursting into tears. “There’s all these questions,” she sobs, looking at the paperwork in front of her.

“I’m so sorry,” Taylor says.

“It’s just that last time my lips swelled up and I had this ringing in my ears, and then I was better. I went home and took some Benadryl and slept all day, but I can’t do that today,” says the teacher, before breaking down again.

“Well, how about, could you reschedule it for next week?” Taylor asks.

“Will they let you do that?

“I don’t know but I could go right over there and ask and see if they will. Just tell them you’re not feeling well.”

The teacher gestures to the forms in front of her. “It says, ‘Are you feeling ok?’ I don’t know. I’m afraid if I don’t get it, I won’t get it. I’m just too afraid to come back. You know what I’m saying?”

“Right, I understand. We need it,” says Taylor, referring to the vaccine.

But the teacher leaves without getting her second dose.

The hesitancy illustrates how challenging it is, even in places where there is great trust between health care workers and residents, to get communities vaccinated.