‘Extreme Conservation’ in the Most Hostile Places on Earth

Joel Berger dresses up in a bear suit to see how muskoxen in the Arctic will react, just one of the ways he’s an “extreme conservationist.”

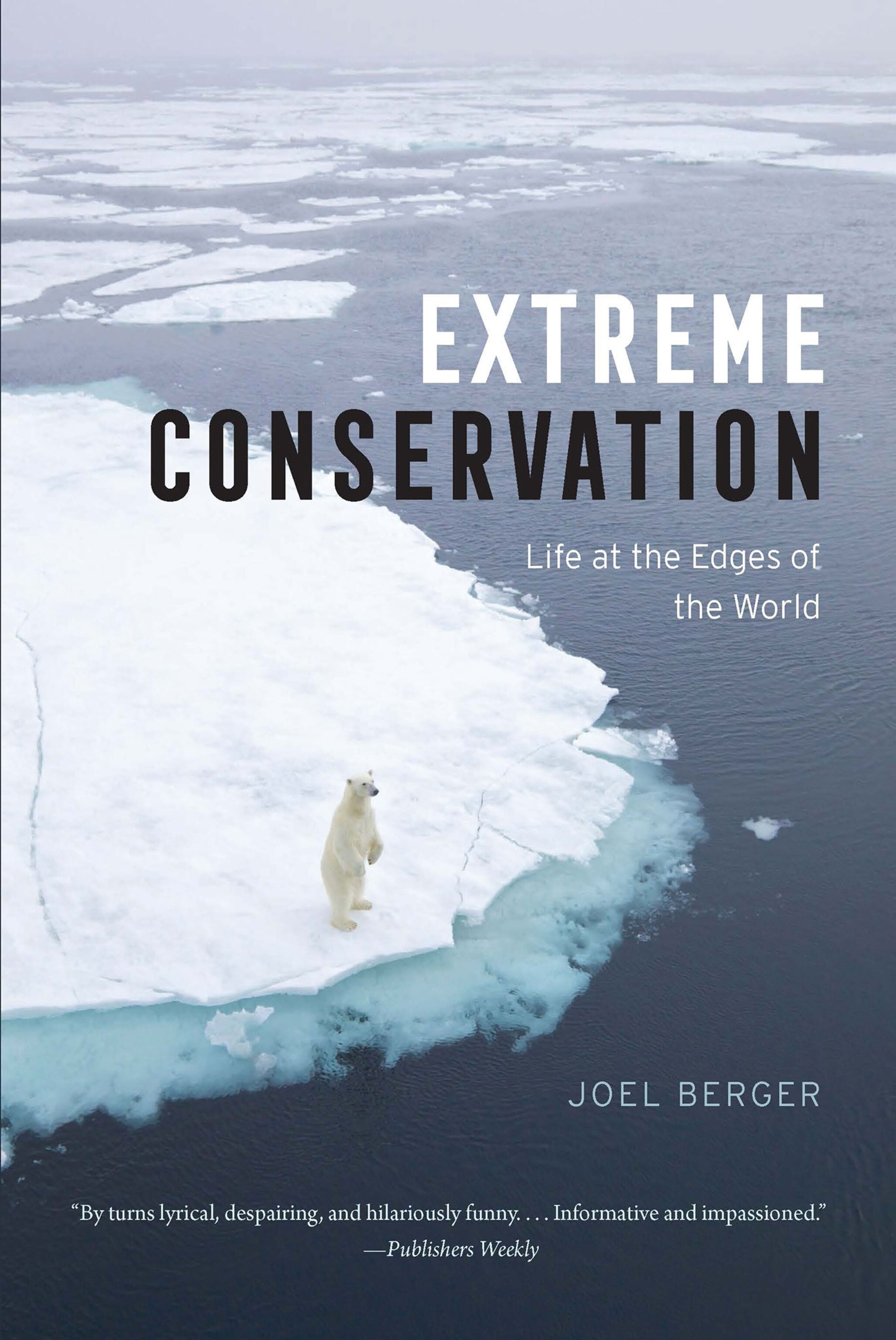

Conserving wildlife at the extreme edges of the natural world, whether in the Arctic, Tibet, or Mongolia, presents huge challenges, from potholed roads (or no roads) to hypothermia, bear attacks, and even arrest. In Extreme Conservation, Joel Berger, professor of conservation biology at Colorado State University and scientist at the Wildlife Conservation Society, takes us on a journey to some of the most remote places on the planet, and introduces us to some of its rarest animals.

When National Geographic caught up with him at his home in Fort Collins, Colorado, he described how he was arrested in Russia, how climate change is bringing more and more species together in new and unpredictable ways, and why man’s best friend is increasingly a menace to wildlife.

Your work focuses on animals living in some of the most inhospitable places on earth. Introduce us to some of these creatures and tell us what draws you to these places. Are you a masochist, or what?

[Laughs] Good question, Simon! I do work in places that are a little bit off the radar. A lot of people know about elephants, say, in East Africa but people don’t know much about a species that lived with woolly mammoth called muskoxen. They’re an Arctic-only species, though they are not an ox and they don’t make musk. They’re more of a goat-antelope. They live in the cold, wind-swept tundra, from Greenland across Northern Canada into Arctic Alaska, and now a little bit into the Siberian Arctic.

As we know, the world is warming. Most people believe that, even if the U.S. administration at the highest levels does not. This creates a lot of issues for cold-adapted species because they’re not used to warm weather. What happens when it rains rather than snows in the middle of winter and then everything freezes? The work I’m doing with my colleagues is both at the top of the world and at high elevations, in the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau. It is dealing with animals that are having problems with heat because as things warm it changes precipitation, ice, and snowfall. And these are very recent changes for these little-known, cold-adapted animals.

One of the odder things your work in the Arctic involved was dressing up as a bear and a caribou. What was that all about?

[Laughs] Most of my work has been in Arctic Alaska and over in eastern Arctic Russia. As the ice recedes, polar bears are ending up on islands and we’re trying to figure out how muskoxen are going to do with this potential predator on land. The best way as a scientist to get information is through experiments. In my case, my lab is the tundra. So I dress up as a bear and approach these groups of muskoxen to try and understand whether they’re recognizing bears. Can they tell a white bear is a polar bear versus a grizzly bear?

Occasionally, it gets dangerous. Male muskoxen are 800 pounds or so, with hooked horns, a bit like a Cape buffalo. I’m usually down on all fours with my fake cape and fake bear head. One time I was charged and I had to get rid of them fast. The fake head went flying up in the air, and the cape flew off in the other direction. Fortunately, the charging muskox got very confused as this biped stood up. All of a sudden, I was no longer a bear, but a screaming human!

Do you travel with your bear suit?

Oh, yeah, I do travel with the bear suit. [chortles] I get on an airplane and put down the fake head right next to me on the seat. The people sitting next door are either horrified or laughing. They’re not quite sure what to think! I’m as straight as can be but sometimes I break up on it, too. [laughs]

One of the surprising developments in the Arctic is the convergence of brown and polar bears. Tell us about so-called “pizzlies” and what they reveal about the changing climate.

Scientists have discovered that at least 10 different hybrid bears have been confirmed for DNA, which means we’re getting mating between brown and polar bears. Because of a warming Arctic, we’re bringing these species together. We now have grizzlies on islands in the Canadian Arctic where they had not appeared before, and we’ve got more polar bears on land scavenging whales and grizzlies scavenging those same whales. We don’t know what the outcomes are going to be. But we do know that we’ve got changing systems because of changing ice in the Arctic. And this has implications not only for the wildlife but also for the humans who subsist on the wildlife.

According to the proverb, dogs are man’s best friends. But they’re not wildlife’s best friends, are they? Talk us through some of the issues in Bhutan and elsewhere.

Of maybe 700 million dogs in the world, close to 50 percent of them are free-roaming in one sense or another. That doesn’t mean they’re totally feral but in places like Bhutan, Chile, and parts of Patagonia we’ve got dogs that are not under much control. Free-roaming dogs have been detected causing havoc in wide parts of the Himalayas and Mongolia, where they’re attacking different endangered species, from snow leopards to chiru, an antelope in Tibet that was the mascot for the 2008 Beijing Olympics. There are also attacks on takin, the national mammal of Bhutan, and other species in Central Asia. We don’t see this in the West so much, where dogs are usually under control. But in many other parts of the world dogs are causing havoc to wildlife.

Like many readers, I suspect, the takin is new to me. Introduce us to this strange animal, and its equally unusual home in the valley of Tsharijathang, in Bhutan.

Takin have been described as part wildebeest, part moose, and part pig. It’s a very unusual species that is rumoured to have been the source for the legend of the Golden Fleece. It’s a large animal, up to about 800 pounds, with beautiful fur, and is part of the goat-antelope group. They occur on cliffs and steep slopes in mountainous areas in China, Bhutan, and Burma. They are secretive, living in forests down low, where they’re a prey of tigers, or up high the young can be the prey of snow leopards. We know very little about them because of the deep forest habitat they occur in. Only in summer, when they migrate very high, do they emerge from the forests, and that’s when we get the best glimpse of them.

When I started my field work with some Bhutanese colleagues they told me it’s a five-day hike to get into the area, with three 17,000-foot passes. I was in my early 60s but I was like, “OK, I’m game, let’s do it!” It was a challenging way to enter some of these pristine landscapes where herders still raise domestic yaks and some horses. Snow leopards also occur in the system, so it’s a fascinating area few people ever see. And, yes, there are takin.

It’ll soon be time to get out our cashmere sweaters again. But according to you we may also be contributing to the extinction of many animals in Central Asia, including the iconic snow leopard. Unravel the threads for us.

Ninety percent of the world’s cashmere comes from two countries: Mongolia and China. The people on the land, the herders, rightfully want to do what the rest of us want, and have a sustainable economy and support their families. But as they increase the number of goats that produce the world’s high-quality cashmere, the goats nibble everything. As a result, a half-dozen endangered species are not having access to the food they need, species like saiga, which is a very odd antelope with a dangling proboscis. Other species that are impacted include Przewalski horses, khulan, an endangered desert ass in the Gobi, and blue sheep, which are not endangered but are major prey of snow leopards. And as the herders are incentivized to produce more and more goats, the situation becomes increasingly more dire for species on the land. Nobody wants people to get impacted, so the difficulty is finding the right type of solutions that can help people on the land but still benefit the species that occur there.

Wrangel Island, in the Russian Arctic, has to be one of the least-visited places on Earth. Put us on the map and explain why you call it a post-apocalyptic landscape.

It can be accessed only by boat or helicopter. But I could not get from my sites in Alaska to Wrangel. I had to fly to Moscow, go nine times zones east, land at a port 240 miles from Wrangel, and wait for a Russian helicopter to drop me in.

I call it post-apocalyptic because not only are there polar bears, but wolves have gotten there on their own, though the nearest point on land is 80 miles away. Caribou have been brought in and reindeer, which have gone feral. Wolverines have also made it from the Siberian coastline, traversing ice and frozen seas to get there. Now you’ve got a mixture going on between hybrid dogs that now look like wolves, or wolves that look like hybrid dogs. Muskoxen were also brought over at the request of the Russian Government, when we had a good relationship with them.

We still participate with Russian scientists, despite some of the acrimony at political levels. Conservation is the province of everybody. And it’s a marvellous place to work! It’s got a lot of wildlife and may be the forerunner of what the world is going to look like as different assemblages of species come together.

You’ve done 33 expeditions, including 19 to the Arctic, seven in Mongolia and seven in Tibet and the Himalayas. Talk us through some of the highs and lows of those journeys.

[Laughs] A major high would be coming across muskoxen and polar bear tracks on one of those bluebird days when it might be 20 degrees Fahrenheit below zero, but no wind, and sparkling ice. One of the lows was flying from Moscow and landing in a Siberian town called Pevek. Russian Security Border Patrol folks came on, I’m the only Americanski on the plane, and I am escorted off, my passport confiscated, and taken to the police station. Everything is being done in Russian, a language I am unfamiliar with, and the only words that I understand are C-I-A. [laughs]

In Mongolia, I ended up in the emergency room because my legs were going into spasms and for three days I wasn’t able to hold any food. But one kind of sucks it up. There are many other scientists and explorers who go out there and do similar things. But we do realize that there are some trade-offs.

At the end of the book, you write, “In the absence of commitment on both global and local scales, the iconic wildlife of the world’s highest mountains and greatest steppes will cease to persist.” Are you optimistic or pessimistic about the future?

There are a lot of reasons to be pessimistic but if that’s the view we choose to take there are going to be no chances. On a personal level, I’m optimistic! There are a lot of countries investing in conservation. Russia has stepped up with 191 islands in the Arctic that are protected as of 2016. Places in Western China the size of California have been linked together for conservation. Chile is planning to link 10 of their national parks. In the U.S., the number of people per year that go to national parks and zoos eclipses all professional baseball, football, and basketball combined. People care about nature and wildlife, and that’s why I am optimistic.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.