What a Gold Rush-era orchard could mean for the future of food

Scientists are beginning to study whether rare heirloom plants, revived for their flavor, might also be suited to enduring a warmer world.

Five thousand feet up in the Sierra Nevada and a half-hour’s drive from the last paved road, a clearing opens at the edge of a forest. The clearing is ringed with pine, fir, and aspen, a dense palisade that shields its contents from a rutted track that runs past its hidden gate. Inside, a meadow harbors more than 100 gnarled trees. It is early September, but the trees’ leaves are still green, and other colors peek out among them: apples crimson and scarlet, pears golden and rusty, almonds and walnuts in globes of dull olive.

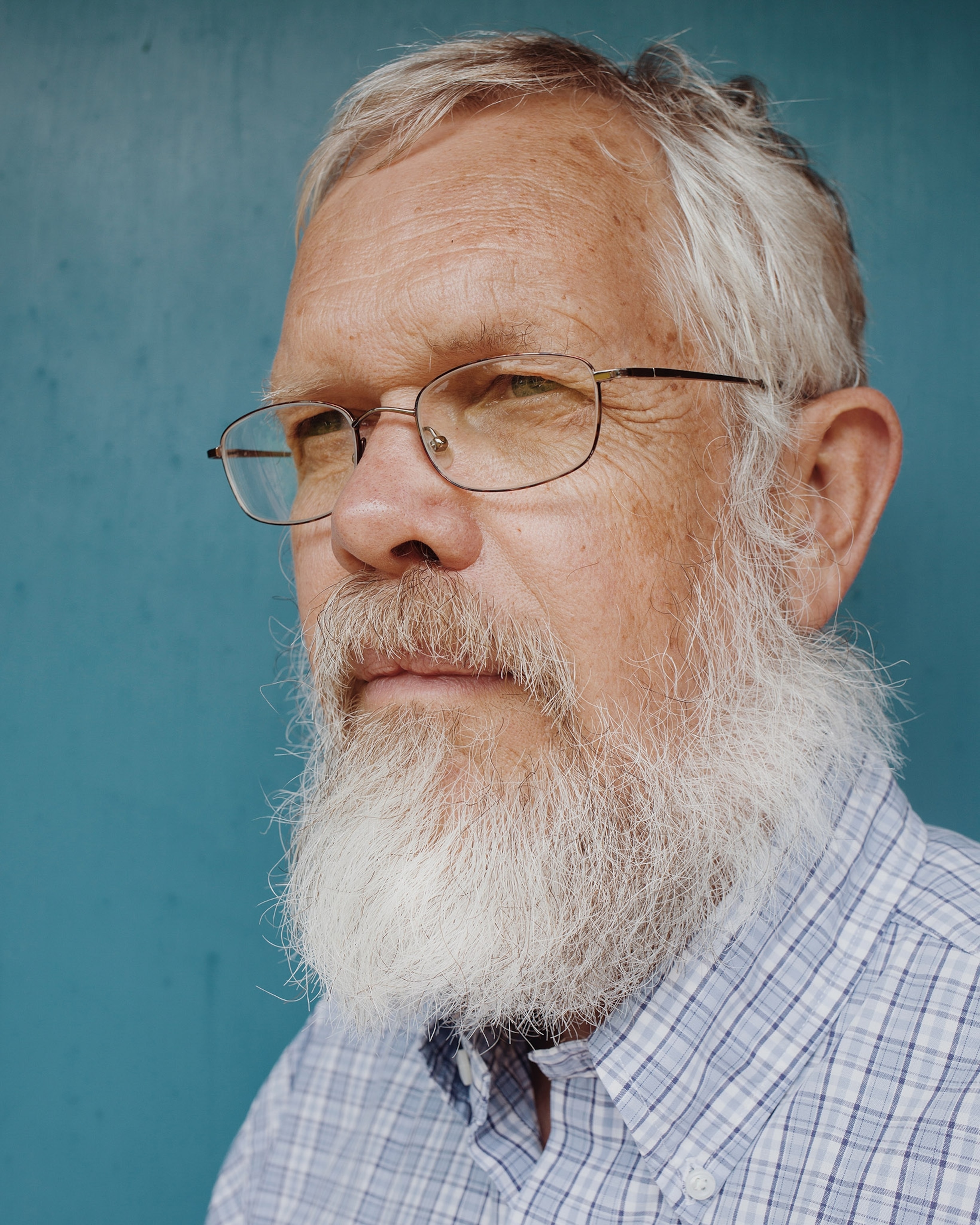

Amigo Bob Cantisano tips back his straw hat, surveying the hidden orchard. “It’s no different than the last time I was here,” he says. “And it’s not much different than the first time.”

That was 1970. Cantisano was whooping through the hills in a 1951 Dodge pickup with the cab cut off, taking a break from his first stab at farming; he stumbled on the orchard while looking for a swimming hole. In the 50 years since, as he grew from neophyte to an elder statesman of the organic revolution, he’s remained devoted to the grove he discovered that day. Piece by piece, talking to old-timers and reading newspaper archives, he reassembled its history. The trees were older than he imagined, the last vestige of a trading post that served the mining camps of the Gold Rush—which meant the orchard had survived, apparently untended, for more than 150 years.

Just 100 miles to the west lies the tip of California’s Central Valley, the richest agricultural land in the United States, which grows the same crops that persist at the forgotten trading post. But down on the valley floor, trees are pruned, sprayed, irrigated, fertilized. Without those measures, their productivity could not be sustained.

The trees of the hidden orchard have remained productive for more than a century without any such assistance. Far from being a lost piece of history marooned on a mountain, the orchard is a treasure chest.

Cantisano’s trees—he doesn’t own the plot but has become its custodian—are heirlooms: historic, open-pollinated varieties that were not swept up in the green revolution, the hybridization that transformed commercial agriculture after World War II.

Back then heirlooms were rejected for what seemed like solid reasoning at the time: They ripened at intervals, making supply unpredictable, grew to odd sizes that did not fit processing equipment, and were too tender to transport across the greater distances that food began to travel as production consolidated. The hybrids that supplanted the heirlooms were more suited to large-scale production and shipping, but often at the expense of flavor and nutrition.

Now heirlooms are beginning to be in demand again—not just at farmers markets, which is where most of us encounter heirloom crops, but in the industries that once disdained them. Plant breeders—and livestock breeders, since livestock underwent a similar hybridization from diverse breeds—are reconsidering their value.

Rare plants and animals are being studied by academic scientists, grown for display in living museums such as Colonial Williamsburg, and brought back from oblivion by small-scale farmers and corps of dedicated amateurs. In heirlooms, their fans see treasuries of biodiversity and resilience, protection against heat, drought, diseases, and pests that will be needed as a changing climate makes current crops and animals—which have been reduced to a narrow genetic range—harder to grow.

“We know these trees are growing in an environment that may be more like the environment we’ll have in the future: hotter, drier,” says Charles Brummer, director of the Plant Breeding Center at University of California, Davis, where scientists are beginning to study Cantisano’s orchard. “These trees have withstood a lot.”

‘Bigger than a baby’s head’

Cantisano—who wears shorts and sandals in every season and has been known as “Amigo Bob” since high school—now farms north of Nevada City, a Gold Rush town in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada. Through patient sleuthing, he traced the trees in the orchard to Felix Gillet, a French horticulturalist.

Gillet arrived in Nevada City in 1859, when gold-panning was giving way to an organized industry of company-owned mines and settlements of camps surrounding them. He put aside cash by working as a barber, and then opened a nursery, shipping in European fruit and nut varieties by boat and train. Merchants and homesteaders bought the trees, and so did farmers, who began growing the produce now synonymous with California. Gillet seeded the state with some of its earliest hazelnut, almond, and walnut varieties, stone fruits such as cherries, and grapes.

To protect the orchard and ensure it continues into another generation—and to preserve other trees discovered at old homesteads and camps—Cantisano formed the Felix Gillet Institute, a nonprofit whose staff consists of him, his wife Jenifer Bliss, and Adam Nuber, who propagates the trees and manages their small commercial nursery. Their near-constant task is hunting down trees across Northern California, taking measurements, recording their growth pattern and condition, mapping their location, and then returning to harvest some of the fruit for research.

Fruit is the best indicator of a tree’s identity, and Bliss serves as the institute’s fruit detective. Each time Cantisano and Nuber visit the orchard and other trees they’ve found, they document when fruit is ripening. At Cantisano’s home, they test harvested fruit for sugar content, and then Bliss pores over a collection of 19th- and early 20th-century fruit catalogs, matching size, color, and sweetness to written descriptions or early photographs. She has matched some of their finds to rare varieties of apples, pears, almonds, and walnuts. Lacking records, they’ve given provisional names to cherries they’ve found in nearby areas, dubbing one Foxy Lady after the family on whose property it was found, and another Camptonville Candy, after the town where it is located.

In September, Cantisano and Nuber agreed to take me to the lost orchard, on the condition that its exact location wouldn’t be revealed. The trees were heavy with fruit, and we had to stay alert and step carefully, because there were piles of bear scat among them, loaded with plum stones and berry seeds. Nuber carried a harvesting basket, a cage on a pole used to pluck fruit off high branches.

“That’s a Spitzenberg,” he says, tossing a candy-red apple into a box. “That’s a Yellow Bellflower. That’s a Reinette—it might be one of the forerunners of the Golden Delicious.” He offered me a bright red apple with green shoulders. I bit into it and was shocked by the fresh, sharp taste. He scooped off another apple, so large it teetered unsteadily on the basket’s edge.

“We called this Bigger Than A Baby’s Head at first,” Cantisano says. “But Jenifer thinks it might be a 20-Ounce Pippin. Felix had it in his catalogs in the 1880s, but it probably came originally from New York.” He looked into the box, his waist-length dreadlocks falling over his shoulders. He pointed out a deep red specimen. “That’s a Calville Rouge. It’s the best storing apple we have. Keeps four, five months without refrigeration, just in a back bedroom.”

Nuber pointed out two trees in the row we were standing in. One was riddled with tiny holes, so evenly spaced it looked like the tree had passed under an industrial drill. The holes were woodpecker damage, a sign the underlayers of the bark had been infested with tasty grubs that the birds had pried out. The tree next to it had no holes at all. “That’s a sign of natural insect resistance,” he says. “We can’t answer why one variety possesses it and the other doesn’t, but we can ask the question, and maybe someone will be able to answer it.”

I realized I was still holding the apple Nuber had handed me to sample, and though I had bitten into it an hour earlier, the flesh was still not brown.

Cantisano noticed my reaction. “That’s one of the things we evaluate,” he says. “We cut them and lay them out, and count how long it takes. We’ve got one that is still white three days later; it’s very high in vitamin C, a natural antioxidant.”

“People are making GMO non-browning apples now,” he says. “And we want to say, There’s no need to go to GMOs. We’ve got the genetics right here.”

Resurrecting heirlooms

Cantisano’s institute, which is funded by donations and by sales of young trees propagated from the originals, isn’t the only organization seeking to bring heirloom varieties back into history. At the other side of the country, the Carolina Gold Rice Foundation has retrieved an array of nearly lost crops linked to Native Americans and early settlers. “Sea Island White Flint corn, Jimmy Red corn, Cocke’s Prolific corn, Guinea Flint corn, purple straw wheat, white may wheat,” says David Shields, the foundation’s chairman and a professor at the University of South Carolina. “We’ve rediscovered the entire grain system of the Carolinas.”

The foundation’s work began with its first resurrection, Carolina Gold rice, a strain that may have arrived in Charleston in the 1600s and vanished from wide-scale production in the 1940s. A few seeds for it had been stored in a USDA seed bank, and in 1998, some were replanted through the efforts of Merle Shepard, a plant geneticist at Clemson University, and Glenn Roberts, the founder of the boutique grain business Anson Mills. Once enough grain had been banked to bring the rice into commercial production, Anson Mills began selling it—and that, Shields says, is one justification for heirloom varieties: There’s a market for them.

“The heirloom corns that we have grown are in intense demand by distillers for artisanal bourbon,” he says. “High Wire Distilling in Charleston uses Jimmy Red, one of the corns we revived; it’s won all kinds of awards. Jeptha Creed Distillery in Kentucky uses Bloody Butcher corn. The flavor of these corns has added a new richness to bourbon; it’s no longer dependent just on the barrel and the char.”

The foundation subsequently committed to preserving any “landrace” crop—heirloom, historic, and open-pollinated—that had survived from before the 1880s. Its chief driver, Shields says, has been flavor, because in traditional plant breeding, flavor was a marker for nutrition, and as industrialization advanced, flavor fell in importance behind a plant’s productivity. But as they bring more old crops back into production, the foundation is identifying other traits that justify growing the plants again.

“These landrace grains actually have more nutrition to them, because they have enormously elaborate root systems, which maximize the uptake of minerals and interaction with the microbiomes of the soil,” Shields told me. “They are less productive than modern cultivars, but they can operate in marginal soils, and they are extraordinarily resilient in the face of drought.”

Stalking fainting goats

“Watch this,” says D. Phillip Sponenberg.

It was a wet, windy day in the Blue Ridge Mountains of southwest Virginia. The advance gusts of Hurricane Florence were pulling wisps of clouds across the hillside where we were looking over a herd of goats. The goats noticed our approach, then went back to grazing, maneuvering to keep an eye on us as they munched. They were blocky animals, seemingly more muscular than a goat ought to be.

As I turned to ask Sponenberg a question, I saw he’d left my side. He was a few yards away, creeping up on the herd’s blind side. Suddenly, he stood upright. The spooked herd ran, but as they sped up, their back legs seemed to straighten strangely. One of the goats went stiff in all four legs; with its head still up, looking startled, it fell 90 degrees on its side. After a few seconds, it stumbled to its feet, shook itself, and took off again.

“And that,” Sponenberg said, “is why they’re called fainting goats.”

As we walked back to the mountaintop house where he has lived for more than three decades, Sponenberg, a veterinarian and professor of pathology and genetics at Virginia Tech, explained the trait. The goats are a heritage breed, the animal equivalent of an heirloom, first identified in Tennessee in the 1880s. The sturdiness I saw was real; the breed had an unusually high meat to bone ratio. With their reaction to shock, they also had no desire to climb or jump, which made them easy to confine. All of that was conferred by a change in a single gene, which also happened to make them naturally resistant to parasites.

Those qualities—disease resistance, docility, productivity, adaptation to a landscape—attracted Sponenberg to the breed. They’re qualities he looks for in other breeds, as a researcher and an advisor to the Livestock Conservancy, a nonprofit that seeks to preserve heritage breeds of livestock.

The Conservancy, headquartered in North Carolina, monitors more than a hundred breeds of livestock and nearly as many breeds of poultry. It works with organizations of growers that raise breeds that have become rare, and recruits new farmers when ranks are growing thin.

“These breeds were bred over centuries to endure drought and extreme weather, to produce through thick and thin, to protect their offspring from predators,” said Jeannette Beranger, the Conservancy’s senior program manager. They harbor traits that commercial breeds discarded: Large Black hogs can have litters of 10 piglets at seven years of age, when a commercial pig would be done at two years old. Gulf Coast sheep will eat grasses grown in brackish water. The original line of Texas longhorn cattle, maintained by a small number of breeders, will bear calves not to four or five years old, but into their teens.

“These breeds are highly suited to certain regions of the world,” she said. “And as different environmental conditions surface, they can meet the needs of the new climate. They’re a bridge between our current animals and what we may need in the future.”

There hasn’t yet been much genetic research into heritage animals: Livestock genetics are mostly conducted in agricultural colleges, which are likely to be funded by the agribusinesses that produce commercial livestock and seeds.

Sponenberg, who also researches heritage lines in South America, thinks failing to study them is a missed opportunity. “Think of them as a genetic insurance policy, preserving diversity so it doesn’t disappear,” he said. “For some species, like cattle and horses, the wild ancestor is extinct; we should save every descendant we can.”

Rare for a reason

The counter-argument against resurrecting heirloom crops and heritage livestock is that they became rare for a reason. Heirloom vegetables and fruits were hardier than commercial varieties, but they did not produce as abundantly. Irregular ripening ensured deliciousness but undermined transportability. Landrace livestock exercised and fed themselves, but at the cost of growing muscle more slowly. And they were so tuned to specific conditions—the Pineywoods cattle of Florida could never endure winters the Ancient White Park cattle of Montana take in stride—that no single breed could be grown at the scale of modern industrial chicken, pork, and beef.

While heirloom crops and heritage livestock might face challenges getting to market, researchers ponder whether the qualities that make them special could be extracted—through traditional cross-breeding or new genetic technologies, leaving the plants and animals that harbor them behind.

Using older varieties to prop up existing industrial ones isn’t unheard of: A wild relative of rice bred into commercial strains protected them against disease; European wine grapes were saved from insect destruction when wild American vines that were resistant to the pest were used as rootstocks, for remnants of European vines to be grafted to.

At UC Davis—where Cantisano has already loaned some lost varieties to its walnut breeding program—Brummer says the first step is to understand what the hidden orchard contains.

“The ideal thing would be to bring them into a nursery where we could compare them to commercial varieties, under commercial conditions, and see how they perform,” he told me. “See what their yield is or their quality or disease resistance.”

It’s possible, he points out, that varieties that do beautifully in the forests of the Sierra Nevada might not flourish away from that complex ecosystem—and also possible that those trees may already be thriving somewhere in California agriculture but simply attributed to a different provenance or under different names.

The value of diversity

For livestock, there are a few options, none of them perfect. They can be grown as they are now, in small populations by a few breeders; that keeps them adapted to changing conditions, but risks narrowing their biodiversity. They can be crossbred, which creates a new animal but does nothing to maintain an existing breed. Or they can have their genetic material frozen, which preserves genetic diversity but sacrifices adaptation. The USDA maintains a bank of livestock germplasm—sperm, eggs, and other cells—and scientists have used it on rare occasions to resurrect old varieties to mix into new crossbreeds.

Tim Safranski, an advisor to the germplasm program for swine preservation and a professor of animal sciences at the University of Missouri, says that—as with heirloom crops—we may not have enough information to make those decisions. “We don’t have the heritage breeds well characterized,” he told me. “We know diversity is valuable, but we don’t know which parts of it are most valuable.”

At least until more knowledge is gained through genetic study, Safranski is in favor of making sure no heritage breeds are lost. To explain why, he told me about one company’s experiment that examined whether hogs will stay productive in a warming climate. In locations around the world, an agribusiness (which Safranski didn’t name) measured the number of piglets produced by two breeds of pigs—a hybrid designed to have large litters and one closer to a landrace sow—as the temperature changed around the year.

The commercial pigs produced more piglets, until the ambient temperature rose above 72 degrees, and then litter sizes dropped. The landrace pigs initially seemed less productive than their modern cousins, birthing fewer piglets in each litter. But as the temperature rose and the hybrids dropped fewer piglets, the landrace ones kept popping out the same number—and their productivity surged ahead of their modern cousins. Their slow sturdiness won out in the end.

“The less perfect the world gets,” Safranski says, “the more competitive they become.”