What causes coral bleaching? Here’s how it threatens ocean and human life

Coral bleaching isn’t just an ocean crisis. Here’s how the global event endangers food security, local jobs—and the land itself.

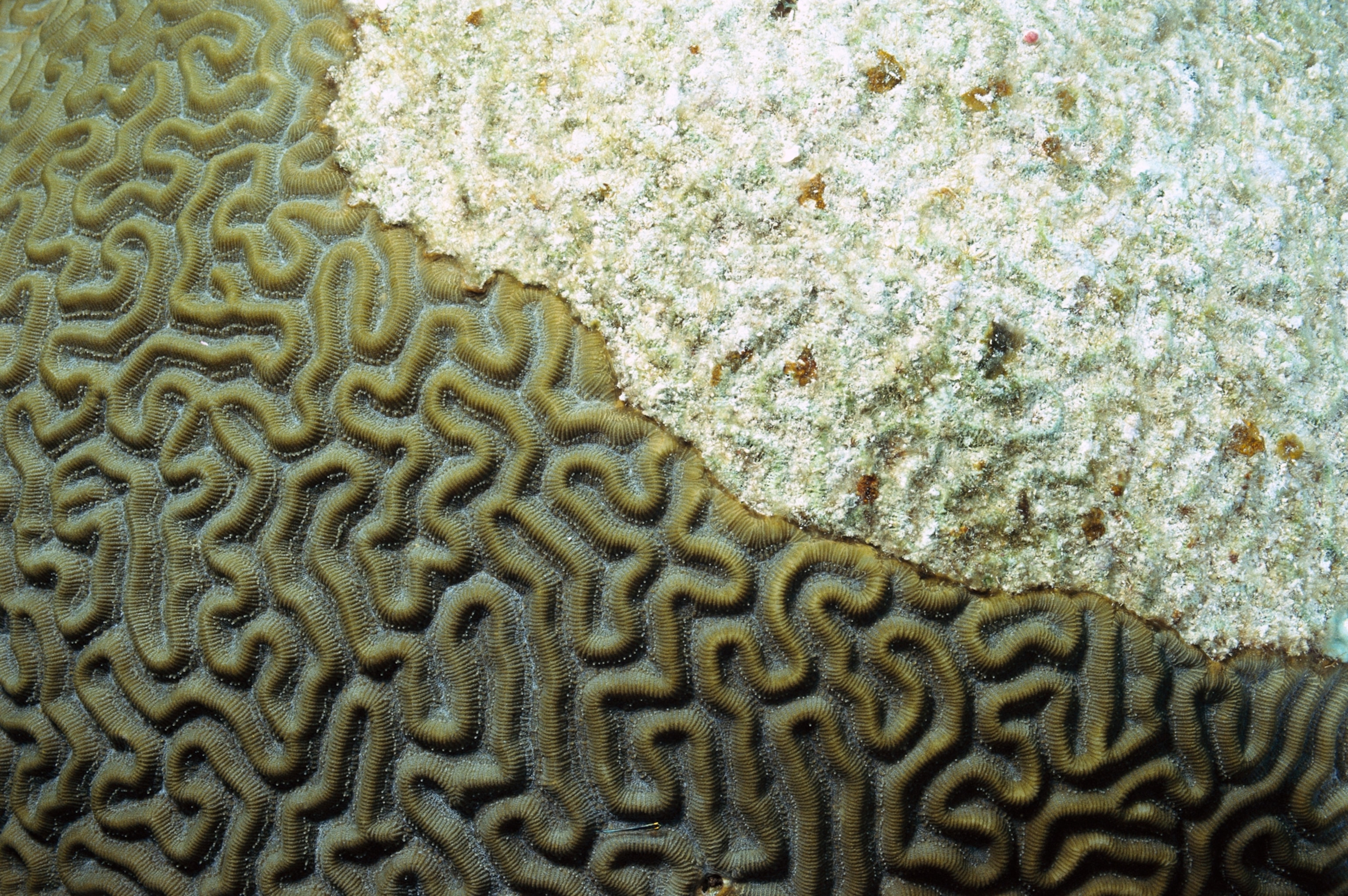

The transformation of a once-bustling coral reef into a white ghost land is visually striking, coral bleaching also threatens ecosystems and economies around the world.

As global warming continues, coral bleaching is becoming more of a problem worldwide with 84 percent of the world’s reefs affected by heat stress between 2023 and 2025.

Coral reefs aren’t just marine biodiversity hotspots, they’re critical to human life. When reefs die, the impact ripples across food systems, local economies, and climate resilience, especially in coastal communities.

Here’s everything you need to know about bleaching, its impacts on marine life and human communities, and how we can save our reefs.

(Five reasons why our coral reefs have hope)

What is coral bleaching?

Tropical coral reefs are known for their rainbow of reds, oranges, pinks, and purples, which are produced by a microscopic algae that lives inside the coral tissue.

“Corals have this partnership with a tiny little algae called zooxanthellae,” says Molly Timmers, a marine ecologist for National Geographic Society’s Pristine Seas project. In this symbiotic relationship, the algae inside the coral converts sunlight into food through photosynthesis, and shares this energy with its host. Up to 90 percent of a coral’s energy comes from the zooxanthellae, also known as algal symbionts.

Certain changes, especially increased ocean temperature, can upset this delicate balance. Prolonged heat stress causes corals to expel the algae living in their tissues and turn white, becoming highly vulnerable.

“When coral gets stressed, it's like you and I getting sick,” says Timmers. “We sweat when we're recovering from something.” The coral expels the algae as a stress response. Without it, the coral loses its color and main source of food.

(These photos show what happens to coral reefs in a warming world.)

When coral bleaches, it isn’t dead—yet. “They’re on life support,” says Michael Sweet, professor of aquatic biology at University of Derby in the United Kingdom.

Bleaching impacts a coral’s ability to reproduce and to create mucus, making it more susceptible to disease. In the ocean, “corals are bathed in this microbial soup,” he says. Like snot in a human’s nose, mucus helps them capture and get rid of harmful bacteria. “The mucus is the first line of defense.”

If normal environment conditions return quickly, the algae do too. If not, the coral can quickly starve to death. “It can shut down and just give up, and then it dies quite instantly,” says Sweet.

What causes coral bleaching?

Warming oceans—caused by climate change—are typically the cause of coral bleaching. It can also be triggered by pollution, acidification, sedimentation, and changes in salinity or water quality.

“There's lots of things that can change in an environment that will cause this relationship to shift,” says Timmers. Even being exposed to the air during extreme low tides can cause bleaching.

Mass coral bleaching events—when large-scale coral mortality occurs in several species—are becoming more severe and more frequent. Global bleaching events occurred in 1998 and 2010, while the longest and most damagingspanned from 2014 to 2017. During this mass bleaching event, two thirds of the Great Barrier Reef were impacted and widespread coral mortality occurred.

(How travelers can help protect the Great Barrier Reef's corals.)

Most recently, the world faced its fourth global bleaching event from 2023 to 2024, after unprecedented marine heatwaves. The Great Barrier Reef was again impacted—in its southern range, 80 percent of coral colonies were bleached by April 2024. Experts are worried about the reef’s potential for recovery and warn that things might get worse.

How coral bleaching affects marine life and coastal communities

Coral reefs support 25 percent of the world's marine life. Their structures provide a home, feeding, breeding, and nursery grounds for many fish—housing that’s a good deal more efficient compared to the flat seabed. “You can house more people in a 20-story apartment building than a one-story building,” says Timmers.

When corals die and animals lose their home, mobile species migrate and those who can’t move might die out—disrupting the food web. “Things get out of whack,” she says.

Coastal communities lose their main food source as well as livelihoods dependent on tourism and hospitality.

Their loss can have a cultural impact for Indigenous communities who value natural ecosystems. The Hawai’ian story of creation tells that polyps—the individual organisms that make up the coral colony—were the first animals created. Corals being the very first thing to appear from the darkness demonstrates their importance to the community.

(How trash from ancient humans is protecting these coastal islands today.)

The disappearance of coral also puts coastal infrastructure at risk. Reefs act as natural breakwaters that can reduce wave energy by 97 percent. Without reefs buffering the shoreline, waves hitting land are more powerful. “Seafaring people know that when you have fringing reefs, the wave energy is stopped before your community,” says Timmers.

Stronger waves pummeling the coastline also increases the risk of erosion and flood damage.

How to stop—or slow—coral bleaching

Scientists are developing various ways of protecting corals from bleaching. One method involves shading corals from the hot sun using underwater parasols made from cloth. Some experts are preserving species in controlled “biobanks” to keep them safe from extreme conditions in the wild. Others are supporting restoration efforts by breeding or moving heat-tolerant corals to new areas. Marine protected areas, fisheries management, and pollution measures are also important.

Some researchers are even experimenting with a method known as known as cloud brightening, or manipulating the clouds above reefs to make them more reflective and therefore keeping the waters cooler.— However, critics worry about potential unintended consequences, such as changes to weather patterns.

“Prevention is better than cure,” says Sweet. “We need to tackle climate change. That should always be front and center.”

Experts say if we take urgent action now, reefs around the world can recover and thrive. “It is devastating, what is happening,” says Timmers, “but there's still hope.”

(Meet the man who sinks the world’s biggest ships for a living)