Why the Drake Passage is one of the most dangerous—and important—places on Earth

The Drake Passage is infamous for the “Drake Shake,” but the ocean crossing also plays a key environmental role.

The Drake Passage is one of the most treacherous bodies of water in the world. That didn’t stop six voyagers from crossing it by rowboat in December 2019. For 600 miles, explorer Fiann Paul led a team of athletes who rowed against the wind and waves studded with ice shards to reach Antarctica.

“Cold and wet,” said Paul, describing what it was like. “It’s dirty.” The short waves that struck in quick succession were the worst: “They hit you like walls.” Deadly storms blow through this ferocious spot where the Atlantic, Pacific, and Southern Oceans meet.

On maps, the spindly arm of Cape Horn in the Tierra del Fuego archipelago appears to reach across the Drake Passage and the South Shetland Islands to the Antarctic Peninsula.

Although he never crossed it, the passage is named after 16th-century English explorer Sir Francis Drake, who had also been involved in the slave trade. Dutch navigator Willem Schouten is credited as the first person to cross it in 1616.

However, some prefer to call the passage Mar de Hoces, in reference to the Spanish sailor Francisco de Hoces, who may have reached this part of the world 50 years before Drake.

Some of the world’s strongest ocean currents flow through the Drake Passage and huge rogue waves have caused the deaths of passengers on ships there, as recently as 2022. Some voyagers have reported waves in excess of 65 feet.

(Learn more about the North Sea, another source of viral ocean videos)

Most people have never been to the Drake Passage. They may, however, have seen the jaw-dropping videos on TikTok, or other social media platforms, filmed by travelers on ships battered by towering seas. Yet tumultuous waves aren’t the only phenomenon that makes the region so famous.

Why the Drake Passage is so rough

The main reason the Drake Passage is so rough is because the Southern Ocean, which encircles the frozen continent of Antarctica, is unbroken by land, meaning that mighty winds can rush around the globe unimpeded. It also sits on a seismic zone, making it vulnerable to earthquakes.

“It’s always interesting when you go to dinner and they put sticky mats on all the tables to make sure your plates and things don’t slide around,” says Karen Heywood, a physical oceanographer at the University of East Anglia.

How the Drake Passage helps the planet

The Drake Passage is a “melting pot” for carbon capture, says Heywood who researched carbon dioxide in the Antarctic. It’s where extreme ocean currents take carbon, including that deposited by plankton, down into the depths where it could be stored for centuries. Strong currents in the passage also transport material from the Pacific thousands of miles away to the North Atlantic.

(Would the world really face chaos if the Atlantic’s ocean currents slowed down?)

The passage plays an important part in keeping Antarctica cold too, says Alberto Naveira Garabato, a physical oceanographer at the University of Southampton. Without a land bridge to South America, it is much harder for warm air to make it to the globe’s most southerly reaches.

Climate models suggest that when the Drake Passage opened tens of millions of years ago—no one is quite sure exactly when—it contributed massively to the cooling of Antarctica.

(These ocean threats are changing the planet)

You can feel the chilling effect of the Drake Passage when you cross it on a ship, says Naveira Garabato. “Suddenly you are in this icy world,” he explains. “It happens just like that—you can see the transition happening only in hours.”

The cooling power of this unique place means that, somewhat ironically, the very dangerous Drake Passage helps protect the planet.

If Antarctica were a much warmer place, and the 11.5 million square miles of ice packed around the continent melted tomorrow, global sea levels would rise by more than 195 feet.

The Drake Passage might also be a “hot spot” for carbon sequestration. The carbon storing processes studied by Heywood and her colleagues could be especially efficient here compared to other places on Earth, says Lilian Dove, an oceanographer and assistant professor at Georgia Institute of Technology.

(Sinking land and rising seas: the dual crises facing coastal communities)

Dove’s research suggests that the ocean is less stratified in this region, thanks in part to high winds and the irregular form of the seabed. That means that phytoplankton, for example, which capture carbon from the atmosphere, might be swept down into the depths in huge volumes.

The Drake Passage could, then, be one of a handful of carbon sequestration hot spots in the Southern Ocean, which, collectively, removes 600 million tons of carbon from the atmosphere every year. That equates to roughly one sixth of all the carbon emitted by human activities annually.

(How pulling carbon out of the ocean may help remove it from the air)

The Drake Passage and the Antarctic ecosystem

It’s important to remember the abundance of non-human life that thrives in the Drake Passage and other places around Antarctica, says Naveira Garabato.

Vigorous currents transport nutrients far and wide, supporting life from plankton and krill all the way up to the largest whales. “The entire Antarctic ecosystem rests on this sort of upwelling,” he says.

(Blue whales are going eerily silent—and scientists say it’s a warning sign)

Fiann Paul vividly remembers the penguins, dolphins, and whales that he and his team saw when they finally approached their goal, Charles Point on the Antarctic Peninsula, at the end of their rowing adventure.

By ship, it takes roughly two days to cross the Drake Passage, although tourists these days can also “fly and cruise,” combining a ship crossing and a flight. They had made it after 13 days of dueling with one of the wildest places on Earth.

(See the surprising ways climate change impacts Antarctica)

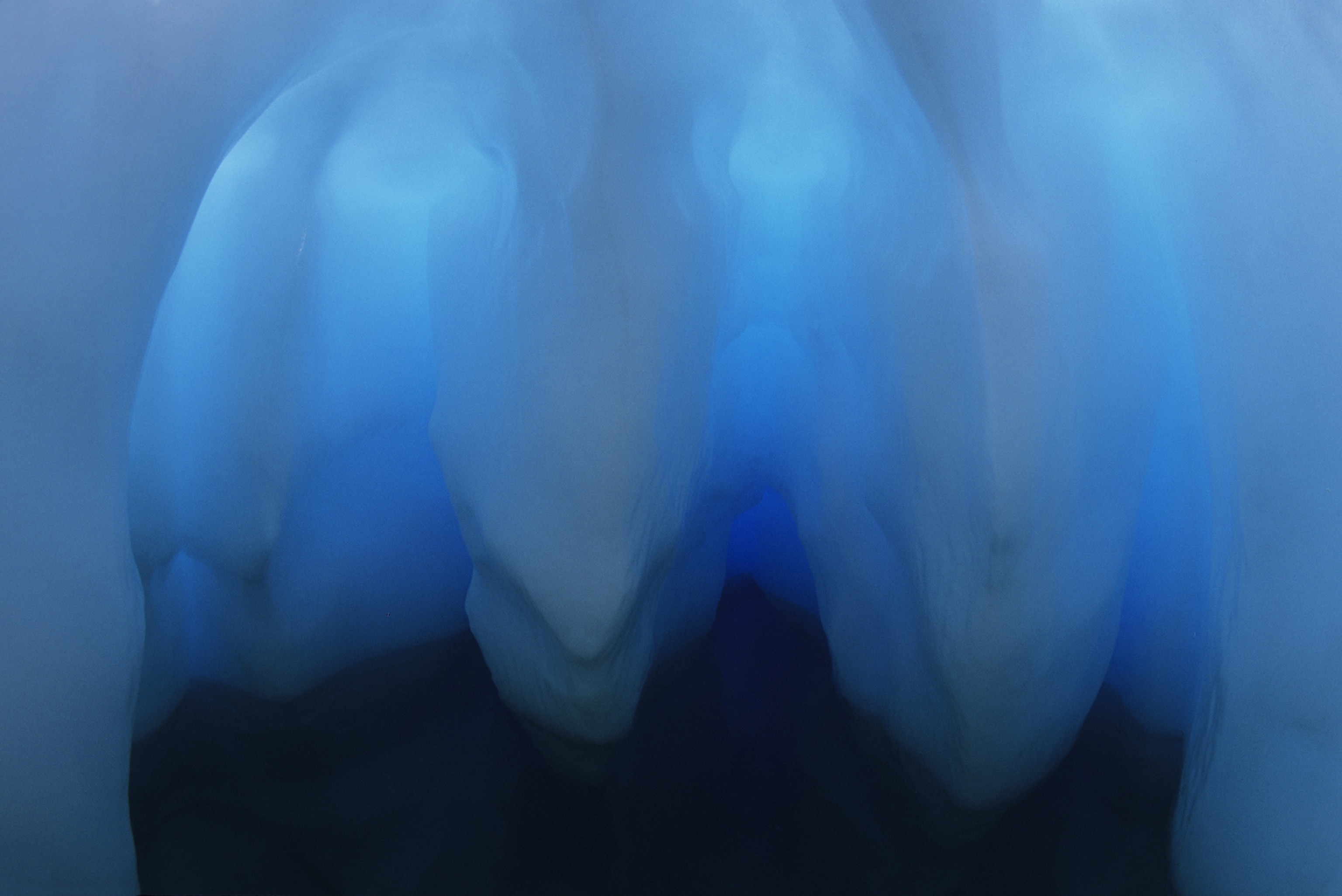

After all those squally seas and gray skies, suddenly the bright white ice of Antarctica beckoned them, the sides of that ice colored here and there an electric blue.

Paul says that some members of the expedition were so overjoyed to see the continent after making the arduous journey across the Drake Passage that they were moved to tears: “It’s such a beautiful place.”