Why hurricane flooding is about to get even more dangerous in Florida

Florida’s coral reefs provide protection from hurricane storm surges—and experts estimate that losing key species in those reefs could imperil thousands of lives.

In July 2023, Katey Lesneski dove into the ocean off Key Largo to visit Horseshoe Reef, one of the largest and healthiest natural stands of elkhorn coral remaining in the region.

Normally, she wears a wetsuit to protect against the cold, but that day she didn’t need one—the ocean was unusually warm. “The water didn’t feel refreshing,” she recalled.

As she peered through her diving mask at a reef that had taken centuries to grow, she saw that every single coral had turned ghostly white, their tissue sloughing off in chunks.

“I was seeing the coral actively dying, losing the tissue. And once that happens, there’s no coming back from it. I was crying underwater into my mask,” said Lesneski, a scientist who leads Florida’s Mission Iconic Reefs program. “It was very sad to witness, and I felt quite hopeless at that moment in time.”

The 2023 marine heatwave caused two important coral species—staghorn and elkhorn—to go “functionally extinct” in Florida’s reef, according to a new study that includes the survey data Lesneski gathered that summer. It’s the first time such a declaration has been made for these two species in Florida. (Another coral species, Dendrogyra cylindrus, was declared extinct in Florida in 2021.)

The region’s corals have faced environmental threats since the 1970s, but the 2023 heat wave increased water temperatures by more than 2.5°C above normal for weeks, causing the mass die-off.

Corals are one of the most supportive lifeforms on the planet, providing habitat for thousands of species and protecting coastlines. But they are in the midst of a global bleaching event, with more than 80 percent of reefs affected by extreme ocean temperatures.

In Florida, the extinction event portends dire repercussions. Coral reefs protect cities from flooding and hurricanes, and scientists say their decline will make storm surge, the floodwaters pushed ashore during storms, more dangerous.

“Coral decline has an impact on how storm surges propagate, how waves propagate, where waves break and lose a lot of the energy before they can hit the coast,” explained Thomas Wahl, associate professor in the University of Central Florida’s Department of Civil, Environmental, and Construction Engineering. “Any decline in coral reefs around Florida will very likely lead to accelerated erosion and more flood impacts from extreme events.”

How corals protect against storm surge

Florida sits at a low elevation, close to sea level, placing the state at high risk of storm surges that can travel far inland, causing property damage and death. About 90 percent of deaths from hurricanes are caused by drowning in storm surge and floodwaters, according to the Florida Climate Center.

The hard, jagged structure of reefs reduce wave energy by up to 97 percent. “They basically act like a natural wave breaker,” Wahl said.

Florida’s Coral Reef stretches 350 miles from North Palm Beach on the southeastern coast of the state all the way south to the Dry Tortugas, west of the Florida Keys. It protects populous cities like Fort Lauderdale, Miami, and Key West from the effects of frequent hurricanes. Human-caused climate change is both killing the reefs and increasing the intensity of hurricanes—a dangerous combination.

“If there isn't continued healthy coral growing on the top of these reefs, we see erosion, and the reef starts to break down,” Lesneski explained. “So, you lose the height of that natural barrier, which then leads to more wave energy getting through to the coastline, more coastal erosion, more flooding during storms.”

Most of Earth’s coral reefs formed thousands of years ago, after the last ice age, but global heating is threatening their existence. The University of Exeter’s Global Tipping Points report—which includes the research of 160 scientists from 87 institutions in 23 countries—estimated that when global temperatures reach between 1°C and 1.5°C of warming, reefs will die off so dramatically that the entire ecosystem can’t recover. The planet has now reached 1.4°C of warming.

“This reef has been here for thousands of years, and in just a few decades, we’re seeing it disappear,” said Rachel Silverstein, CEO of Miami Waterkeeper. “That should be a shocking example of how quickly we’re changing this planet.”

Annually, Florida’s reefs provide flood protection to more than 5,600 people, and $675 million in averted property and economic damages, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. With a 3.2-foot loss in reef height, flooding from a 100-year storm would increase by 7.7 square miles, imperilling 24,000 more people and $2.9 billion in property and economic activity.

Reefs create a strong buffer before waves can hit shore, explained Rich Karp, one of the lead authors of the new study. Instead of waves slamming onto shore near people’s homes, reefs cause waves to break off shore.

Karp, a researcher with the University of Miami’s coral program, said scientists thought elkhorn coral would become extinct in 2030 or 2040, but the 2023 marine heatwave showed how quickly they can be wiped out. Scientists were shocked that as little as a 2°C increase in temperature was enough for many corals to bleach.

“These corals had been slowly declining over the last several decades. But what was very striking is how quickly one event is able to basically erase and decimate them across such a large geographic area,” Karp said.

What can be done?

Florida is adapting to sea level rise and storm surge by elevating residential buildings and roads above flood levels, building sea walls, and improving stormwater management infrastructure. But the state needs to maintain natural barriers like marshes, mangrove stands, oyster reefs, and coral reefs in order to combat climate change.

“There have been studies that looked at the entire U.S. and came up with numbers of how much flood loss is being avoided by having those nature-based features in place. And the numbers were pretty big. We're talking billions of dollars every year that are being saved from having those natural features,” Wahl said.

Wahl added that it’s important for Florida to maintain these natural barriers to combat the effects of climate change. “Those features are there so we don't have to build them and pay a lot of money to have them there to function as buffers,” he said.

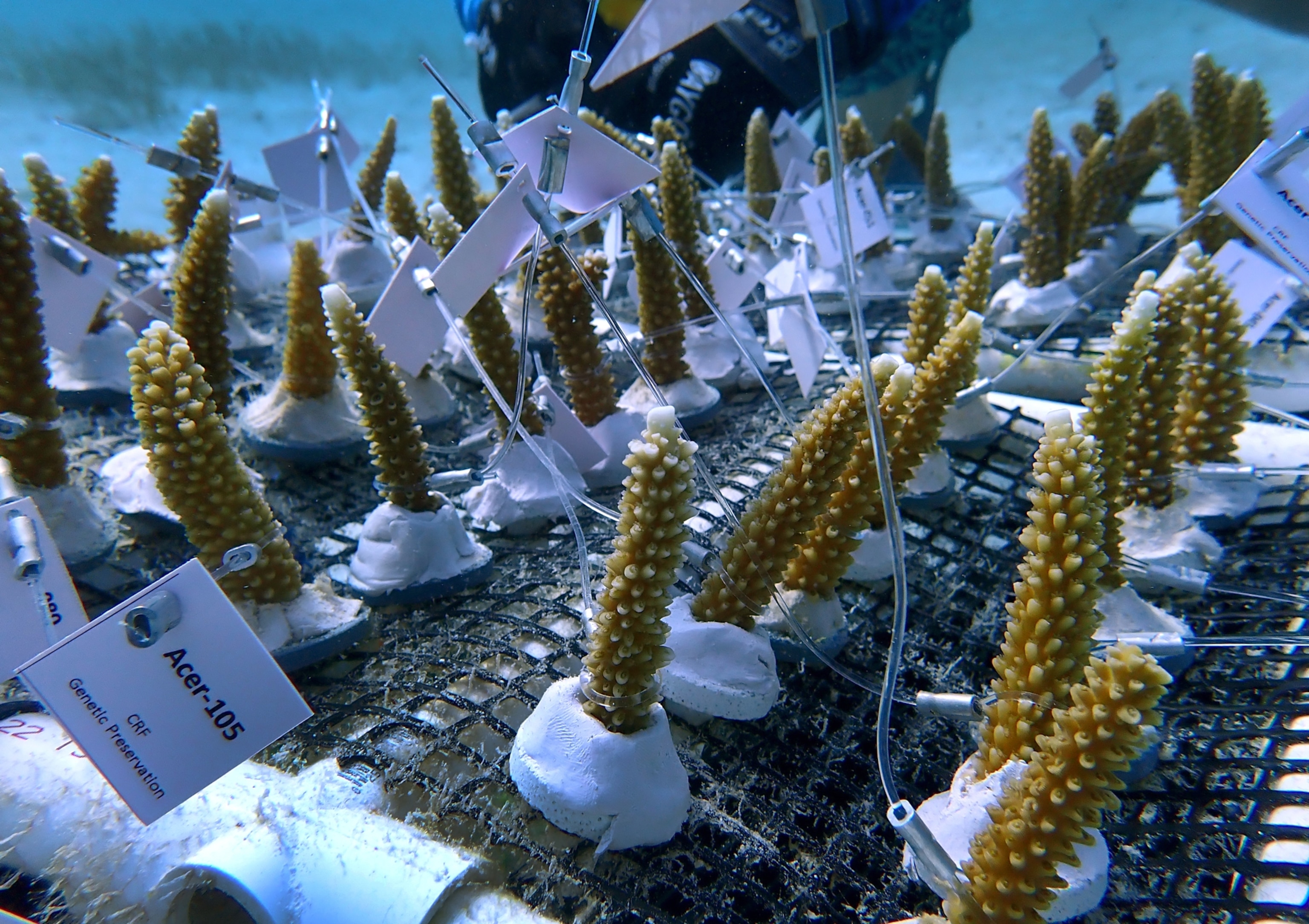

For decades, scientists have been trying to reduce reef loss by growing baby corals in nurseries and planting them onto reefs. But facing more heat waves and dead coral, scientists are increasingly using genetic tools to create new strains of coral that are more tolerant to heat and disease. Coral researchers, collaborating across borders, are taking corals from warmer waters near Honduras and interbreeding them with Florida corals to create “Flonduran” corals that they hope will survive future heat waves.

To protect coastlines, it’s critically important to preserve those existing reefs, Silverstein said. She’s fighting a dredging project that threatens to bury corals in sediment near Port Everglades—one of the last places where staghorn corals are still thriving in Florida.

Ultimately, experts say it’s impossible to save reefs while the planet continues warming.

“We’re going to get to a point where if we don't address climate change, we will not have corals anymore,” Silverstein said. “All of this restoration and heat tolerance will get you another couple decades, maybe, but eventually you're going to reach a point where the oceans are not supporting this ecosystem anymore—and we're very near that point.”

Lesneski emphasized that restoration efforts have already extended the life of Florida’s coral reef. “If there hadn't been all of this effort towards restoration in prior years, our reef absolutely would be in a worse position than it is now,” she said.

She is not ready to give up, saying, “It's been tough, but to continue to do this work, we need to have a level of optimism and consider how to do this work better, more intentionally, with the science and potential interventions that we have in front of us.”