Scientists are about to spend a year trapped in Arctic ice

Hundreds of people have undergone intense preparation for an expedition designed to figure out what a warming Arctic means for us all.

They will face some of the harshest conditions on Earth: polar night, complete darkness, heavy storms, and temperatures that can reach almost minus 50 degrees Fahrenheit.

That’s why Markus Rex, the atmospheric scientist leading a 600-person-strong Arctic expedition— the largest ever—has thought of everything that could go wrong.

“We have plans for all events, even possible loss of the vessel,” he says, though he doesn’t think that’s likely.

Named MOSAiC (Multidisciplinary drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate), the $150-million-dollar expedition will last for a full year and involve people from 19 different countries.

It will be the largest and longest Arctic expedition in history and the first major Arctic expedition in a region that climate change is warming faster than anywhere else on Earth.

Leaving from Tromsø, Norway on September 20, the ship will position itself in the transpolar drift stream and float, trapped in ice for a year, to northern Greenland. The expedition will mostly take place on a German ice breaker called the Polarstern, but four additional ice breakers supplied by Sweden, Russia, and China will periodically deliver people and supplies.

Those participating in the leg that takes place over polar night will have to carefully conduct their research. The ecologists studying phytoplankton and algae will only use red lamps (white light could disrupt their seasonal patterns). Guards must wear night vision goggles to scout for polar bears. And days will be highly structured to ensure everyone aboard the ship maintains their circadian rhythms.

What makes the grueling trip worth it?

Arctic temperatures are warming, and that influences more than sea ice.

“The arctic is the area where much of the weather is made,” says Rex. “Understanding the arctic helps us understand extreme weather.”

The contrast between cold air at the poles and warm tropical air, helps keep the polar jet stream evenly blowing across the northern hemisphere. When that temperature difference decreases, the jet stream wobbles, and a swirling mass of cold air called the polar vortex is able to send blasts of frigid winter air south.

Experts say this weaker jet stream is partially responsible for the cold snap that made parts of the U.S. colder than the Arctic this past winter. Research has also linked a weaker jet stream to more heatwaves and floods.

“Ultimately the whole design is to improve our models,” says Matthew Shupe, an earth scientist at the University of Colorado and NOAA’s Earth System Research Laboratory who will be on the expedition. “That’s why we’re out there. I think we’ll learn so much more about the physical processes that will help us in our predictive capabilities.”

Shupe began pursuing a yearlong Arctic trip in 2009 after a six-week-long expedition in 2008 left him feeling like his time to conduct research was over before had begun.

“I had no idea where the ice came from [and] where it was going after we left,” he says.

It had to be a year, he and other Arctic researchers agreed. A year of taking precise measurements and watching seasonal changes could give them the raw data they needed to create the kind of climate models that tell us what might happen as the top of the world warms.

This time Shupe will be watching the clouds.

“There are all kinds of wonderful things about clouds in the Arctic—their radiative effects and effects on the surface energy budget that determines things like melting and freezing of the sea ice,” he says.

“We’ll get to see the whole movie of how the ice cover evolves,” says Don Perovich, a sea ice physicist at Dartmouth who will be joining the fifth leg of the expedition at the end of May.

He wants to know what happens to heat absorbed by the ocean. Does it melt the underbelly of the ice? The sides? Or maybe it stays trapped in the ocean, where it could affect the following year’s ice formation, creating a positive feedback loop that accelerates warming.

“This is a question I posed when I wrote my PhD dissertation in 1983, so I’ve been thinking about it for a long time,” he says.

How did passengers prepare?

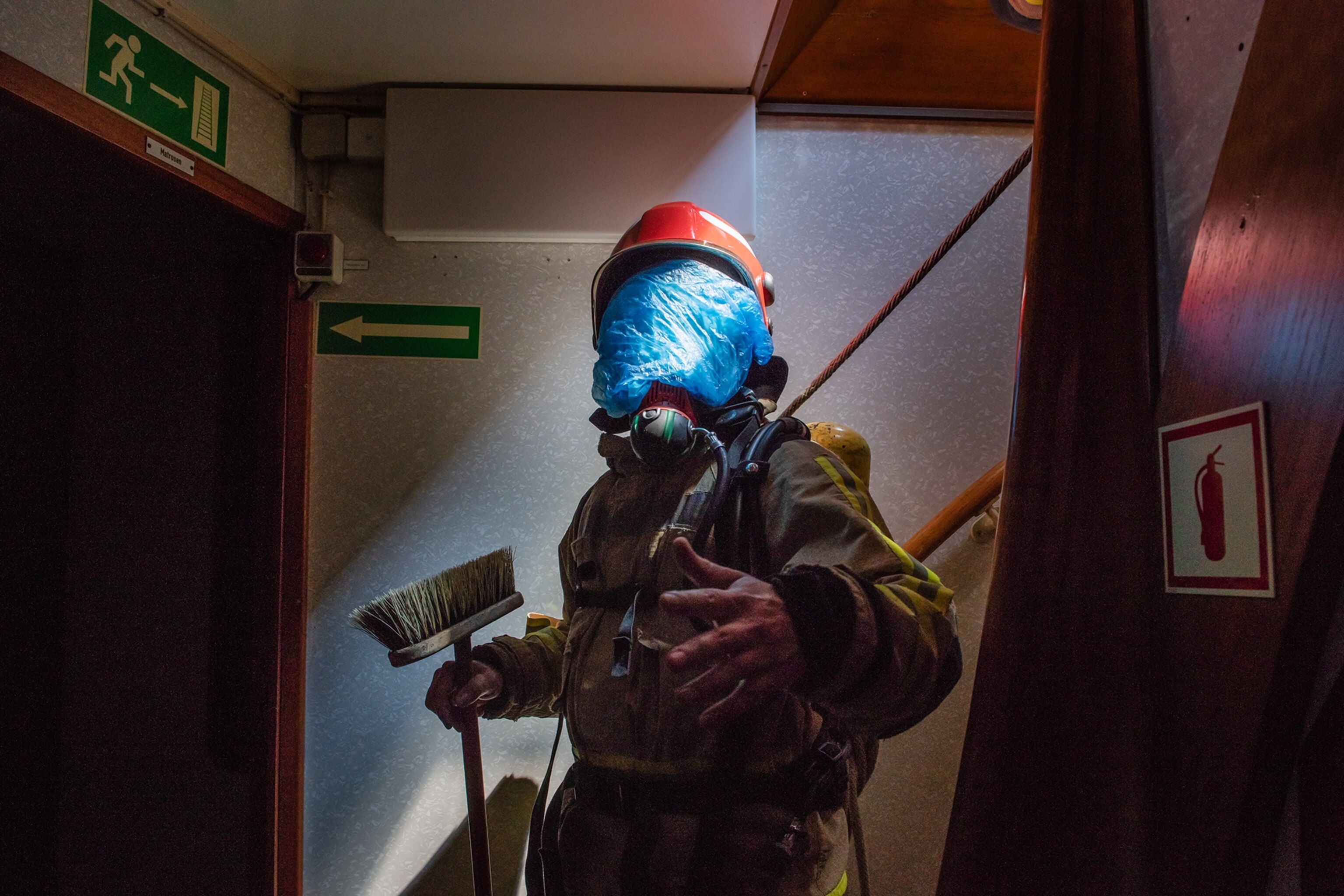

Researching on the ice is physically challenging, and should an emergency happen on or off the ship, passengers could be days away from help. That’s why many boarding the Polarstern had to pass a rigorous training program where they were trained in firefighting, simulated ship evacuations, and shooting rifles in case of a polar bear attack.

“Polar bears are nothing new to me,” says Hans Honold, a polar bear guard for the first leg of the trip.

Honold served in the German Armed Forces, and later specialized as a mountain and polar guide. He thinks the polar night could be psychologically challenging, but says the extended time away from home will be nothing new.

At every research station on the ice, Honold and his team will construct a two-mile fenced perimeter. There, he’ll sit perched with night vision goggles, scanning the horizon. If a bear is spotted, the party must immediately return to the ship. If they don’t have enough time, the ship will blast its horn in an attempt to scare off the bear.

A non-lethal flare gun and pepper spray are the final attempts before a rifle shot is attempted, a last resort that no one wants to see, Honold emphasizes.

“Everything is possible with a polar bear,” he says. “Some are dangerous, but most are only curious and want to know what’s going on—‘is that something I can eat?’”

Other challenges during the expedition will come from living in close quarters, sharing space with strangers, and time away from loved ones.

“We don’t have a psychologist on board, but our leadership has some training in dealing in high stress situations and people who are close to a crisis,” says Rex. “Everybody knows we depend on each other.”

The Polarstern also comes equipped with a sauna, swimming pool, and gym to fill brief moments of downtime.

A lasting legacy

Perovich likens the MOSAiC expedition to a famed 1896 Arctic trip led by Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen, who set out to be the first to reach the North Pole. Though unsuccessful, Nansen’s ship floated along the same current the Polarstern will take.

(See what Antarctica looked like 100 years ago.)

One hundred years after explorers were racing to the North Pole, the Arctic has warmed significantly. Research suggests that the Arctic is warming twice as fast as the rest of the Northern Hemisphere.

“It’s the first big Arctic Ocean experiment in the new Arctic Ocean,” says Perovich.

“The legacy is the data. We’ll be collecting this incredible dataset in the hopes that people will use it for decades to come,” he adds. “We want to be able to predict what’s going to happen. To do that we first have to observe what’s happening and understand what’s driving those changes.”