The Cuyahoga River caught fire 50 years ago. It inspired a movement.

On June 22, 1969, Cleveland's filthy river ignited for the 13th and last time. It and other American rivers are dramatically cleaner today.

Cleveland, Ohio — It’s a warm late spring day and the rowers, kayakers, and paddleboarders are out in force on the Cuyahoga River. A heron stands motionless along the river’s edge under an old railroad bridge, not far from where the river empties into Lake Erie. Restaurants and bars line the banks.

Fifty years ago such sights would have been unimaginable here. On June 22, 1969, there weren’t any rowers or wild birds on the river. There hadn’t been any fish—or any other living things—in its waters for decades. On that day the river was burning.

It would turn out to be a cleansing fire, one that became a potent symbol for the nascent environmental movement. Within a few years the U.S. had enacted laws that would have a dramatic impact on the environment, including the Cuyahoga and other rivers.

Frank Samsel, an 89-year-old Cleveland native, designed and operated a boat in the 1970s called the Putzfrau (German for “cleaning lady”), which played a key role in sucking up chemicals and scooping assorted solid debris from the Cuyahoga. Samsel vividly recalls the river in the summer of 1969.

“It smelled like a septic tank,” he says. “It literally bubbled and produced methane in July and August. It wasn’t bad—it was terrible. You can’t describe it using printable language.”

On June 22, the fire started around noon, when a spark from a train crossing a bridge fell into the toxic stew of industrial waste on the river’s surface. Smoke and flames, some as high as five-story buildings, erupted on the river from bank to bank. Hard as it is to believe in today’s era of ubiquitous phone cameras, there’s no photographic record of the conflagration, which caused about $50,000 in damage to two railroad bridges. A fireboat—the Anthony J. Celebrezze—extinguished the flames within 20 or 30 minutes, before any photographers arrived at the scene.

It wasn’t the first blaze on the river, nor was it the largest. But it was the last.

Thirteenth time’s the charm

Like many cities and corporations, Cleveland now has a director of sustainability, Matt Gray. “What’s astounding to me is that the first fire was in 1868—1868!” Gray says. Just 30 years earlier, he notes, the French historian Alexis de Tocqueville had visited Cleveland en route to the Great Lakes and described the region’s waters as the most pristine he had ever seen.

Rapid industrialization changed all that. The Cuyahoga would burn at least 12 more times over the next century. One fire, in 1952, caused more than $1.3 million in damages; another, in 1912, killed five dock workers. None of those disasters, however, ever achieved the notoriety of the 1969 fire.

What made 1969 different?

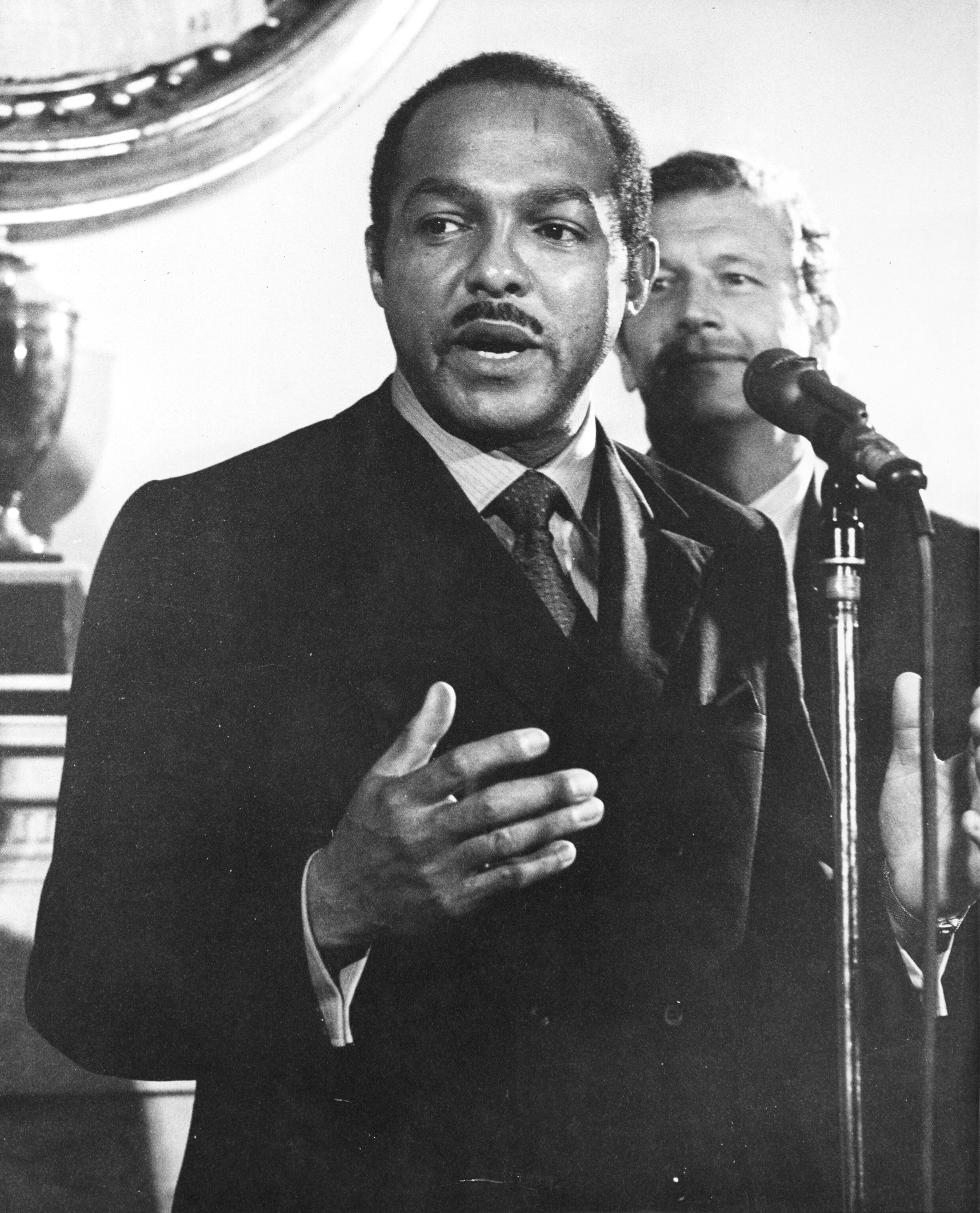

On the day after the fire Cleveland’s mayor, Carl Stokes, held a press conference and requested help from the state government to clean up the river. As the first African-American mayor of a major city, Stokes was a story in himself. His presence at the site of the fire helped transform what might have remained a local event into national news. Later that summer Time magazine ran an article about the blaze (illustrated somewhat misleadingly with a photo of the larger fire in 1952).

Earlier in 1969, a catastrophic spill off the coast of Santa Barbara, California, had released three million gallons of oil into the ocean, creating a 35-mile-long slick. Photos of thousands of dead birds and marine mammals, followed a few months later by news of a burning river in Cleveland, helped galvanize environmentalists. The first Earth Day, already in preparation, was held ten months after the Cuyahoga burned. Within three years Congress had created the Environmental Protection Agency and passed the Clean Water Act. Among those voting for that legislation was Carl Stokes’ brother Louis, Ohio’s first black Congressman.

Without the Clean Water Act and the Clean Air Act, which was strengthened in 1970, the neighborhoods around the Cuyahoga might have remained the way Cleveland’s current mayor, Frank Jackson, remembers them from his childhood. “When I was a kid the houses were orange from all the pollution from the smokestacks,” Jackson says. In his wood-paneled office in City Hall, a painting of General Moses Cleaveland, who first surveyed the area in 1796, spans an entire wall, showing the officer on the banks of a forested Cuyahoga.

When the last fire struck in 1969, Jackson had just returned from Vietnam, and he admits he didn’t pay much attention. He’s paying attention now. Throughout this summer the city will host a series of events to commemorate the fire as a pivotal moment in its own history and in that of environmental action.

“We’re not celebrating the fire,” Jackson says. “What we’re celebrating is the fact that the fire was a catalyst.”

Like Lazarus

Jackson has ambitious plans for Cleveland. He joined 400 mayors across the country to commit to the goals of the international Paris Climate Agreement after the Trump administration withdrew from the accord in 2017. The city’s Sustainable Cleveland initiative aims for an 80 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, with 100 percent of its electricity coming from renewable sources by that date. Six wind turbines are set for construction on Lake Erie by 2022.

As for the Cuyahoga, in March the Ohio EPA declared that fish in the river, such as carp, channel catfish, and smallmouth bass, were safe to eat—albeit no more than once a month, owing to the persistence in the sediments of mercury and PCBs.

“About 70 species of fish now thrive in the river,” says Gray. “Pretty unimaginable from 1969 to what we see today.”

On a sunny Saturday morning some of those fish are taking refuge in specially constructed shelters attached to the steel and concrete bulkheads that line the banks of the last two miles of the Cuyahoga before it enters Lake Erie. The shelters consist of submerged chain-link enclosures that encourage the growth of algae, providing food for young fish on the last leg of their journey to the lake. The fish share the narrow channel with 700-foot freighters that deliver iron ore to a steel mill upstream.

Jane Goodman, executive director of Cuyahoga River Restoration, a nonprofit group, points to one such fish-and-algae habitat, not far from the riverside fire station that responded to the 1969 fire.

“People can see fish leaping out of the water here in the industrial shipping channel,” Goodman says. “We had become the poster river for everything that could go wrong with a river. Now we’re a poster river for everything that can go right. It’s the Lazarus river—it came back from death.”