How to start aging like an athlete

These over-50 champs—and a growing body of research—show what we gain by staying active later in life.

For Nora Langdon, the moment of truth came on the stairs. She was 64 years old. Up to that point, Langdon had lived a largely satisfying life. She’d raised two kids, had good friends, and was in her third decade as a real estate agent in the Detroit area.

But as time went by, she’d gained weight, slowly at first, until suddenly she hit 220 pounds. She’d never been an athlete—never played sports, hit the gym, or exercised consistently—but she wasn’t a couch potato either. Her dad had worked in a steel factory, waking the kids at 5 a.m. for prayer and breakfast, and at night they all helped with the family’s soul food catering business. In her world, effort had always mattered. And yet here she was, struggling to make it to the second floor while showing houses to potential buyers.

She began to worry. She’d seen retirees fall prey to a sedentary lifestyle. “Ten years later, they’re gone because they don’t do anything but go home and eat, eat, sit down, and look at the TV,” she says. “I saw a lot of my friends pass away because they weren’t strong enough.” She wanted no part of it. “I said, No, I’m not going out like that.”

At her birthday party, she got to talking with a friend’s husband by the name of Art Little. Wiry, enthusiastic, and no-nonsense, he worked as a trainer at a gym for powerlifters north of Detroit. He invited her to come in for a workout. Langdon wasn’t sure; she’d never done any weight lifting and had always considered herself “a weakling.” When Langdon showed up, Little led her to a bench. Around them, thick-necked men grunted. Weights clattered. Little instructed Langdon to lie down, then lowered a broomstick into her hands. It weighed less than three pounds. Up and down she went with it, fighting gravity the whole way.

That night, she returned home exhausted. Her body ached everywhere, years of disuse coming to bear. She was reluctant to return, but a little voice in her head told her she couldn’t quit—not after one session. So she went back to Little’s gym later that week and then the week after. Little pushed her to add weight—from broomstick to empty barbell, then to the bar with plates. Each time, she told him she couldn’t do it. “Just try it,” Little responded. She did, finding she loved the feeling of getting stronger. Soon enough, with Little’s encouragement, she entered powerlifting competitions and began collecting gold medals in her age-group, even some for bench press—a long way from her first session. Now in her ninth decade, she is stronger than most women in their 20s and 30s.

Langdon is not alone. More people are not only exercising longer and later in life—they’re also competing and breaking records in a range of sports. In Pennsylvania, a computer programmer took up running again in his 50s and now holds the fastest marathon time for a 70-plus runner. In Idaho, a mountain biker racked up world championships while discovering that prioritizing mental health rekindled her love for the sport—and helped her stay sharp. And in Ireland, after a string of injuries, a former rugby player learned that finding the right sport for a changing body sometimes takes persistence. Today he’s the Guinness World Record holder for being the first man to swim a mile in ice-cold water on all seven continents.

These athletes are remarkable examples of a broad but quiet revolution in how we understand human potential across a person’s lifetime. Hirofumi Tanaka, a leading researcher on exercise and longevity, views “masters” athletes—typically those hardy souls who keep competing beyond the age of 35—as a compelling model of what he calls “exceptionally successful aging,” thanks to their ability to preserve strength, endurance, and cardiovascular health well into later life.

“It’s really staggering,” says Tanaka, director of the Cardiovascular Aging Research Laboratory at the University of Texas at Austin. “If you look at the world record [for any given sport], that’s basically stagnated. They haven’t changed that much over the last 10 or 20 years.” But age-group records, he says, are a different story. “They are improving rapidly.”

(Aging isn’t just about decline. Here’s how health improves as we grow older.)

These athletes aren’t just aging well; they’re redefining what aging can look like. Longevity is one thing, quality of life is another. In recent decades, scientists have turned their attention to lengthening the stretch of life spent active, healthy, and engaged, called health span. The goal is no longer just to extend life but to expand the years you can truly live well.

Read more of our reporting in Older, Faster, Stronger

While diet matters, of course, and medicine and genetics play a role, exercise is the linchpin when it comes to health span. It improves heart health, lowers the risk of cancer, increases bone density, aids in cognition, reduces the prevalence and impact of Alzheimer’s, and decreases symptoms of depression. A 2024 longitudinal study in Circulation found that logging 300 minutes of moderate weekly exercise, or 150 minutes of intense activity, can lower mortality risk by roughly 30 percent. By another measure, every minute you exercise adds five minutes to your life.

Here, we highlight a handful of record-setting athletes from their 50s to their 80s. Each extraordinary competitor provides insight into the lessons and emerging science of aging athletes—and gives us all something to strive for.

(It's not your life span you need to worry about. It's your health span.)

The powerful impact of weight training

Only a few months into her new life at the gym, back in 2006, Nora Langdon was already feeling the benefits. She was becoming steadier on her feet, stronger through the core, and more confident under the bar.

Like many older adults, Langdon likely experienced sarcopenia—the age-related loss of muscle mass that accelerates with inactivity. Sarcopenia can lead to a host of negative outcomes: reduced mobility, increased danger of falls, a lack of independence. The good news: Lifting helps counteract those effects. A 2024 study published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology found women who do strength training are more likely to live longer and have a lower risk of death from heart disease compared with women who don’t. Those who participate in strength-based exercises had a 19 percent reduction in mortality risk from any cause and a 30 percent reduction in mortality risk from heart-related conditions—and the benefits for women are even more pronounced than for men.

In Langdon’s case, she steadily lost body weight, dropping almost 20 pounds, but also gained muscle. Within months, she was pushing around enough weight that Little suggested she enter her first state powerlifting tournament. When Langdon arrived, she was in awe of all the strong women—most of them much younger than she was. Then she got under the bar. To her shock, she took home the women’s 60-69 age-group gold in all three events she entered, squatting 190 pounds, bench-pressing 95, and deadlifting 250.

(What lifting weights does to your body—and your mind.)

After another year of training, Langdon advanced to the nationals and then to the 2008 World Championships in Palm Springs, California, where she squatted 330 pounds and won her age-group’s gold medal. Since then, she has set more than 20 national and world age-group records, logging personal records (PRs) of 203 pounds in the bench press, 381 pounds in the dead lift, and 413 pounds in the squat—a mark she set in her 70s. (Her bench press and dead lift PRs remain U.S. records in the 70s age-group.)

Now 82, Langdon still trains religiously, three days a week, for three to four hours, usually wearing Converse high-tops and eschewing headphones to better focus on the task at hand. She drinks protein shakes on the days she trains, eats beef twice a week, and swears by an elixir of a tablespoon of apple cider vinegar in a half glass of water. “All I want to do is inspire other people just to get up and do things,” she says.

But the challenge for most is getting started; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found only 7 percent of American adults do strength training three times a week. If they can make the leap to take up weight training, the effects begin to compound: A study in the Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports found older people gain not only muscle mass but also confidence and motivation.

(When does old age begin? Science says later than you might think.)

Langdon says she feels as if she keeps getting stronger, even at her age. And she has no plans of stopping, either. Not until, as she puts it, “the Lord tells me to go on my own.” In the meantime, she’ll be in the weight room three times a week, without fail.

Starting late can help you finish stronger

When Gene “Ultra Geezer” Dykes revived a long-dormant athletic passion, he discovered his delayed commitment to competitive running might be a secret weapon.

Dykes grew up in Canton, Ohio, and ran in school, then drifted away from the sport. He became a father to two daughters, took up golf and bowling, and focused on his job as a computer programmer. When Dykes was in his early 50s, a friend recommended that he join a running group in the Philly suburbs, where he lives. Soon the group persuaded Dykes to enter races, including a half-marathon. He loved the competitiveness of road racing, and had a blast running trails. In November 2006, at age 58, he lined up alongside more than 35,000 other qualifiers on a cool day in Staten Island at the start of the New York City Marathon. Not only did he finish, but he did so in under four hours.

Immediately, Dykes wanted more. With his kids grown and retirement lined up, he put down the five iron and began running—a lot. He ran with friends, with his daughter, by himself.

(Why running, the world’s oldest sport, is still one of the best exercises.)

Over the ensuing two decades, Dykes—a slight man with an ever present smile—ran thousands upon thousands of miles, setting age-group records in everything from 8Ks to marathons to 50Ks. He won his age-group nearly every time he competed in the Boston Marathon. At 69, he survived the sun-scorched, 240-mile Moab Endurance run in Utah, a giant loop covering desert, canyons, rocky slopes, and two mountain ranges. Defying reason, the Ultra Geezer—a name bestowed by his daughter—got faster as he aged. In 2018, at age 70, he ran a 2:54:23 marathon, not only the fastest ever by a 70-plus runner but also a full 10 minutes faster than his PR of a year earlier. At 75, he broke seven masters records during a solo 12-hour race at Pennsylvania’s Dawn to Dusk to Dawn Track Ultras.

How did Dykes do it? His late-life surge may be telling. We’ve long been told to use it or lose it, but Dykes’s case provides a counterpoint. “We tend to think they’re lifelong athletes,” researcher Hirofumi Tanaka says of elite masters performers. “But they’re not. Many of them actually started competing after they retired.”

How and why is the focus of one of Tanaka’s current studies. For the past five years, he and his team have set up a testing station at the World Masters Athletic Championships—most recently in Gainesville, Florida—to compile data from competitors. Each year, they release new data on associated medical trends, and Tanaka’s next paper, for which the team is still analyzing data, specifically looks at the tread on our physiological tires. Tanaka’s hypothesis: Some younger athletes go so hard that they develop osteoarthritis and other conditions that keep them from competing later in life. “But those people who remain sedentary when they’re younger, they preserve their joints, they preserve their ligaments, and now they can blossom as an athlete.”

Dykes believes this to be the case. He recommends that you “save your money and your legs for retirement.” Looking back, he believes the whirl of professional life and fatherhood may have been the best thing that ever happened to him. “It made me delay my hard running until I was older,” he says. “I tell people, ‘You young guys, you’re competing against Olympic hopefuls. I’m competing against people six feet under. It’s a lot easier.’ It was a blessing in disguise.”

While Dykes started late, he also operates at a different level than his age-group peers—not to mention plenty of runners decades younger. After Dykes’s record-setting 2018 marathon performance, researchers at the University of Delaware tested his physical markers, including his body composition, the economy of his running pace, and the volume of oxygen he could process per minute based on his weight, known as VO2 max. This is a key measure of aerobic fitness that reflects how efficiently the body uses oxygen during intense exercise. (It was, Dykes says, the first time he’d run on a treadmill and, he vows, the last.)

(New clues are revealing why exercise can keep the brain healthy.)

They found that Dykes’s VO2 max of 46.9 milliliters was nearly double the average for a typical 71-year-old, and was far higher than that of most marathon runners regardless of age. According to the Delaware researchers, who published their findings in the New England Journal of Medicine, most marathoners maintain 75 to 85 percent of their maximum oxygen uptake; Dykes performed at 93 percent. As you might imagine, these markers are closely tied to health span: VO2 max is not only one of the best indicators of overall fitness, but is also one of the strongest predictors of longevity. In fact, studies show running is associated with a host of life-prolonging factors, including improved cardiovascular health, enhanced immune system, better weight management, and reduced risk of chronic diseases.

Dykes followed a training plan that was as unconventional as he is. It’s based around what he calls the four F’s: faster, farther, frequently, and fun. He’d pick a period of time—a month, a year—and try to either put in more mileage, increase his pace, or run more often. “And, of course,” he says, “always have fun.” Meanwhile, he avoided stretching, strength training, and special diets. Like weight lifter Nora Langdon, Dykes never wore headphones, preferring to enjoy his surroundings instead.

But in 2022, something changed in Dykes’s body. While running, he began to feel weirdly fatigued. He thought: Oh boy, is this what it’s like to get old? During a 5K, he found that he could barely run. He decided to see a doctor—and good thing he did. The doctor took tests and diagnosed Dykes with blood cancer. Treatment began immediately, and, fortunately, he went into remission. Dykes being Dykes, he was back racing two weeks after the good news. Now he takes daily medication and is hopeful he can manage the incurable but treatable cancer the rest of his life. He credits racing. “I would never have found out about it if I weren’t a runner,” he says. “Maybe eventually, maybe when I dropped over dead.”

The diagnosis hasn’t stopped him from running, but it has changed his approach. After years of logging high mileage, believing that, as he says, you’ve got to have your mind overrule your body sometimes, he is now listening to his body and trying a reset. The 77-year-old ran the Boston Marathon in April and then began an extended break in which he plans to rest, try new recovery techniques, and, he hopes, prepare for the next potential goal: all those 80-plus age-group records that await.

Calm your mind, push your limits

For most of her athletic life, Rebecca Rusch felt invincible, the rare athlete able to switch sports effortlessly and, seemingly, push past most natural limits. Then, in midlife, a freak accident coupled with the stressors of menopause forced her to make hard choices—and led to a new appreciation for her mental health.

Born in Puerto Rico, Rusch lost her father—a U.S. Air Force F-4 pilot—at age three when he was shot down during the Vietnam War, a loss that would come to shape much of her life. After running competitively in high school, she discovered climbing, notching the first female ascent of El Capitan’s Bermuda Dunes trail in 1996, and went on to become an early champion in the emerging sport of adventure racing—a grueling blend of trekking, mountain biking, paddling, and navigation that demands both endurance and resilience over days-long wilderness challenges.

(Who decides to run the Boston Marathon in their 70s? These legends.)

At 38, she pivoted to solo mountain biking and came to dominate the sport. She won the Leadville Trail 100 MTB, a high-altitude course in the Rocky Mountains, then won it three more times. Twice she finished first among women in a 350-mile bike race on the Iditarod Trail over ice and snow in the Alaska wilderness. And she became the only person to bike the length of the Ho Chi Minh Trail through Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, a feat spurred by her quest—ultimately successful—to find her father’s crash site. She’s now won seven world championships and is enshrined in the Mountain Biking Hall of Fame.

Even so, as Rusch approached and then surpassed 40, her body—the one that never failed her—began to change in real time. She needed sleep more than ever but had a harder time getting it (our sleep quality and duration decline the older we get). Recovery took longer. On top of all that, she began navigating menopause: hot flashes, joint pain, staccato sleep patterns. Then, in 2021, she crashed and hit her head on a rock during a trail ride, suffering a traumatic brain injury that left her with a host of symptoms—depression, anxiety, headaches.

For Rusch, her crucial change came in the period after the accident, when she began concentrating on the mental aspect of training and recovery as well. She entered therapy, and, after years as a self-proclaimed naysayer of meditation, she began regularly practicing, swayed after she looked into the research. Functional MRI studies have found meditation leads to changes in brain structure and function, including increased gray matter density, which is associated with improved memory and emotional regulation, and altered brain activity patterns, which can enhance focus and resilience under stress. Meditating can be particularly helpful for athletic performance; a 2024 metastudy in Frontiers in Psychology found mindfulness training reduces an athlete’s anxiety, improves performance, and boosts what’s known as fluency—the optimal competitive psychological state, where the athlete’s attention is entirely centered on the task. “It doesn’t really cost anything to meditate,” Rusch says. “And especially for a hard-charging athlete, it’s really interesting. It’s cool to practice sitting still for 10 minutes.”

(Does meditation actually work? Here’s what the science says.)

Rusch began to realize the value of that processing time. Long training rides, which she embarks on without headphones, became “moving meditation.” Along the way, she shifted her mindset, focusing on finding the joy in sport. Instead of tying her identity and self-worth to her performance, she reminded herself that she does this because “it is fun, and it feels good, and I feel better when I am doing it.” She also looked to reframe the pain, darkness, and trauma of her concussion recovery, which stretched on for years, as an emotional growth opportunity. Mindfulness helped. So did self-reflection.

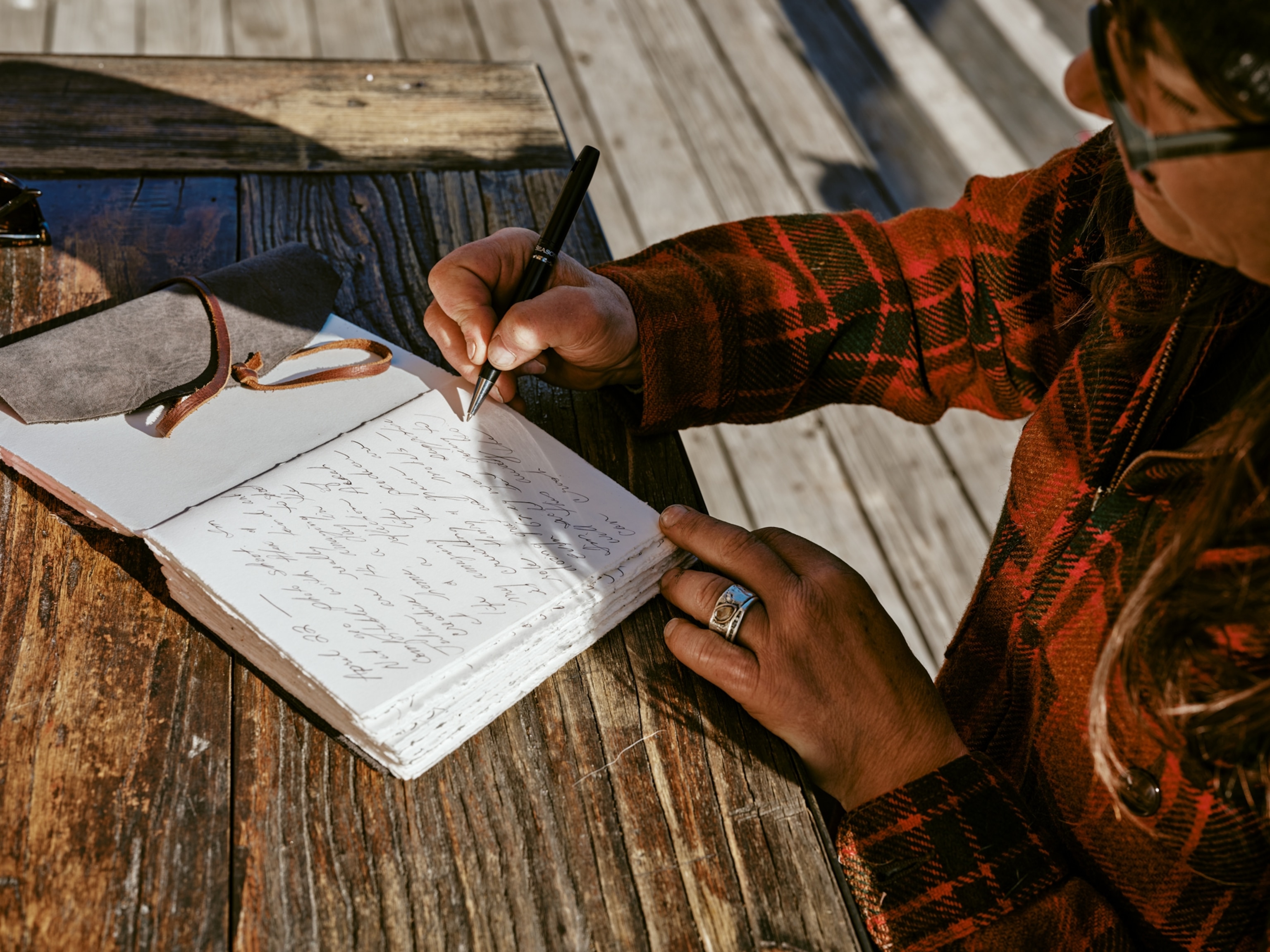

Rusch became a frequent journaler, logging her workouts, reactions, and thoughts in a small notebook. It’s a practice now embraced by many top athletes, including Katie Ledecky, Michael Phelps, and Simone Biles, and studies show it helps with problem-solving, emotional regulation, and competitive stress, and enhances athletic performance. In Rusch’s case, she says the key step is going back and rereading her entries. She compares it to being your own coach or therapist. “It’s actually a pretty interesting way to see what’s surfacing up for you,” Rusch says. “That’s what a good coach would do. That’s what a good therapist would do is just ask the right questions.” She continues: “As I get older, I’m starting to learn that I can ask myself the right questions and be like, What was great about that experience? And just kind of reflect on it a little bit. Or, Why was I in such a bad mood after my run today? Oh, well, I wasn’t really focused. I was distracted by work.”

Today, at 57, Rusch, who lives near the Sawtooth Mountains, in Idaho, values quality over quantity. She often takes off two days a week, and when she works out, she does interval training. But it’s the internal habits—the moments of pause, the willingness to reflect—that now guide her performance. “Who cares how fast you run a 10K?” she says. “The most important part of being an athlete is to feel good and to be able to get up and off the floor and to hang out with your friends and pick up your grandkids.”

These days, mindfulness isn’t something she squeezes in between training sessions. It is the training.

(‘Superagers’ seem to share this one key personality trait.)

Why it’s never too late for a new favorite sport

What do you do when your body no longer allows you to participate in the sports you love?

Growing up on the north side of Dublin, Ger Kennedy played Gaelic football and rugby. By his 30s, he had a family and a full-time job as a plumber—honest work, but not easy on the body. As sports injuries mounted, he traded the crash-and-dash of rugby for running and cycling, entering his first Ironman at the age of 39.

Still, all that pounding on his joints built up. He began experiencing swelling in his knees and hips. “I wasn’t able to run anymore, because the consequences would be two or three days in bed,” he says. “Cycling was good, but the hills were killing me.”

When Kennedy was 40, his doctor diagnosed arthritis in his right hip and knee. Surgeries followed, but Kennedy couldn’t avoid the inevitable; a hip replacement awaited, scheduled a year and a half out, in 2012. During this time, his mental health took a hit. He turned to antidepressants, alongside anti-inflammatories. “I had no way of exercising correctly,” he says. “I’d lost my outlet.”

For anyone, this can be a dark time. Not only do you lose the myriad physical benefits of exercise, from the endorphin rush to improved sleep, but the psychological hit is profound. A 2023 analysis in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health found a direct link between injuries and depression in athletes. Kennedy needed to do something.

With his lower body out of commission until surgery, only one sport remained for Kennedy: swimming. Thanks to the buoyancy of water, the stress on joints is significantly reduced. “Even though we do tell people that walking and running can actually help with arthritis,” says researcher Hirofumi Tanaka, referencing studies that show weight-bearing exercise in moderation can strengthen bones, “the pain is often too much. Water allows you to exercise fairly strenuously without that discomfort.” Indeed, decades of research have shown that swimming is one of the most effective and sustainable forms of exercise for older adults, offering cardiovascular, muscular, and joint health benefits with minimal injury risk.

A friend recommended to Kennedy that he go to the Forty Foot, a historic swimming spot south of Dublin, from which people have launched into the frigid sea since the days of author James Joyce. Kennedy’s first reaction, as he recalls: “You’re off your rocker. No way.” Still, one gray morning he tried it in a wet suit. He eased into the waves and—boom!—the cold walloped him. “My hands, my face,” he says. “I was like, Oh my God, this is crazy.”

Then he got out and he felt better. “I got a lot of relief out of [it], mentally and physically,” he says. Part of that was the exercise. But Kennedy’s choice of where and how to do it also mattered. Immersion in cold water produces a host of physical reactions, including a huge spike in dopamine. Rigorous studies are lacking, but a number of preliminary and anecdotal studies show that it might also help with mental health and depression. A 2023 study in Biology found that after cold-water exposure, participants felt more “active, alert, attentive, proud, and inspired and less distressed and nervous.”

(Swimming just might be the best exercise out there. Here’s why.)

In Kennedy’s case, he kept coming back, swimming out to a set of buoys at 7 a.m. Soon enough, he shed the wet suit. Onlookers told him he must be mad. But he upped his mileage, adding in pool swimming. He joined an informal group of like-minded cold-water acolytes. The sport gave him an outlet, a community, and a purpose again. The blast of feel-good chemicals—and other potential benefits, like immune system strengthening—was a bonus.

Around 2012, Kennedy heard about a new extreme sport: ice swimming. It’s just what it sounds like: swimming in water at 41 degrees Fahrenheit or lower in just a latex cap, a regular swimsuit, and goggles. No neoprene, no gloves, no warm hat. Kennedy had always enjoyed pushing limits. He gave it a go.

Immediately, he took to it. In 2013, at a ribbon lake in Ireland, he attempted an Ice Mile, one of the most daunting—and dangerous—feats in extreme sports, a test of mental and physical endurance that requires covering a mile in ice swimming conditions. Most who try don’t make it. Kennedy not only pulled it off—becoming the 55th person in the world to do so—but that was only the beginning. He took on marathon swims, entered ice swimming championships, and, in 2019, became the first man to complete the “Ice Sevens” challenge, swimming an Ice Mile on all seven continents and in a polar body of water.

Nothing about these swims was easy, which is part of the appeal. Similar to an ultramarathon, ice swimming forces you out of your comfort zone. The urge to quit, to just get out of the water, is overwhelming. Hypothermia looms. But if you stay in, the sense of accomplishment and self-confidence is galvanizing.

Interestingly, Kennedy credits his age—or at least his experience—as an important factor in his success. “I think your own life journey and work adds to your endurance,” he says. Kennedy ticks off stressors he’s faced: his body crumbling, his divorce, parenting, his job as a plumber. “I think all these challenges make you pretty bloody strong.”

Kennedy refers to this as the “endurance brain,” a term he sees as a key to success for aging competitors. “I think that’s why a lot of older athletes—even in American swimming, not just ice swimming, modern swimming—are achieving into their 60s, because they’ve got all this knowledge and skills between motherhood and fatherhood, between screwups and life.”

(This is what a cold plunge does to your body.)

Now 54, Kennedy has completed 19 official Ice Miles and competed in swimming events around the world. He is the chairperson of the Ireland arm of the International Ice Swimming Association. He doesn’t take any of it too seriously—and this may be just as important as anything else. “We do hard-core stuff, but we also have great fun and we enjoy the company,” says Kennedy, who was headed out to an Anthrax show with his mates after a recent interview. “We have a few beers and we laugh at each other.”

He’s determined to swim as long as his body will allow, and still relishes the moments when he can surprise people, like when he recently completed a swim at 78° north latitude, in the Arctic. “No one expected it,” he says with a grin. “They were like, ‘Holy s--t.’ And I said, ‘Yep, the old man’s still got it.’ ” Looking ahead, Kennedy is planning for another Ice Mile.

It’s a theme that runs through the lives of all these athletes and countless others: You don’t stop taking on challenges because you grow old. You grow old when you stop taking on challenges.

The second season of Limitless is streaming on Disney+. Check local listings.