If your menopause symptoms aren't going away, it could be this little-known syndrome

Anywhere from 27 to 84 percent of women experience genitourinary syndrome of menopause—an underdiagnosed condition with profound consequences on your everyday life.

In the run-up to menopause, known as perimenopause, women typically are beset with hot flashes, night sweats, vaginal dryness, and sleep and mood disturbances, triggered by a decline in estrogen levels. With menopause’s onset (officially one year after the cessation of menstrual periods), most women start to experience gradual relief until the symptoms disappear—with one glaring exception.

It’s called the genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), which refers to bothersome vaginal symptoms and urinary changes that not only don’t improve but get worse as women age. Anywhere from 27 to 84 percent of women experience the problem. Yet there’s a good chance you’ve never heard of it.

“It never occurs to women that this is part of menopause,” says Lauren Streicher, medical director of the Northwestern Medicine Center for Sexual Medicine and Menopause. “They think, ‘This is just what happens with aging.’”

(Could this be the end of menopause as we know it?)

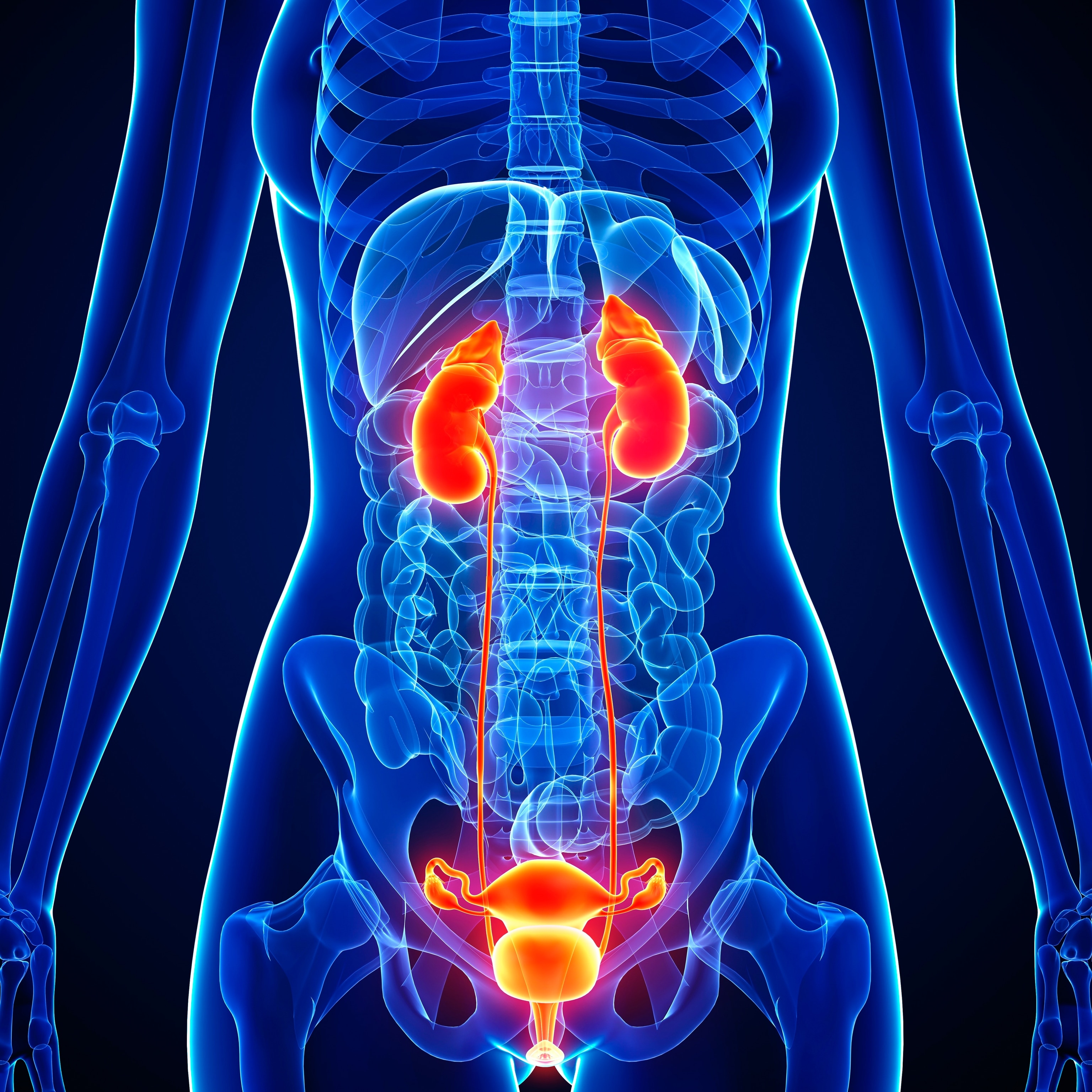

GSM refers to a constellation of signs and symptoms—dryness, itching, and irritation of the vagina and vulva, or outer genitals; decreased lubrication and libido; white or yellowish discharge; painful penetrative sex; and painful, burning, or frequent urination. It can also be the cause of recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs).

Although about a quarter of women experience such symptoms during perimenopause, they are more typical after the transition—sometimes long after. “They can develop 10 or 12 years later,” says Streicher.

There’s a good reason you—or your doctor—may be unfamiliar with the term. Once known as vulvovaginal atrophy, GSM was re-named by a panel of gynecological experts just a decade ago to call attention to lesser known symptoms and its cause. “The hope was that women would recognize that it can be treated,” says Stephanie Faubion, medical director of the Menopause Society and director of the Mayo Clinic Center for Women's Health.

What causes GSM—and how does it affect everyday life?

Dwindling estrogen levels are the culprit behind GSM. Estrogen promotes vaginal moisture and secretions, keeps the vaginal lining thick and the tissue flexible and elastic. When the body starts producing less estrogen, it not only robs the vagina of moisture and lubrication, but affects other tissues as well.

“There are also estrogen receptors in the urethra and bladder,” says James Simon, clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences. The changing environment allows “bad” bacteria like E.coli to flourish in the vagina and urethra, causing irritation and raising the risk of UTIs, he says.

(What happens during menopause? Science is finally piecing it together.)

These changes have a big effect on women’s sex lives. Pain with sexual activity is common among women with GSM who haven’t been treated. A 2013 study of more than 3,000 post-menopausal women found that a quarter of them were enduring painful sex as regularly as once a week. “And if women are used to penetrative sex, it creates a big problem, because now they’re sometimes dreading sexual activity,” says Sheryl A. Kingsberg, professor of reproductive biology and psychiatry at the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine.

Painful intercourse can cause pelvic floor muscles to spasm, compounding the problem, Kingsberg says. So even if a women’s vaginal dryness is eventually treated, they may continue to have discomfort with sex if they don’t also seek help for tight muscles.

The syndrome also has profound consequences for other aspects of women’s health and quality of life, experts say.

“It's not all about sex,” says Faubion. “This is about being uncomfortable in jeans, riding a bike, or using toilet paper to wipe after you urinate.”

Streicher says that women who have GSM often have “vulva awareness—an uncomfortable, itchy, irritated, full feeling” due to dry, inflamed tissue. In a 2019 study, women described itching so severe that they couldn’t fall asleep or a painful dry sensation that forced them to stop taking exercise classes. Some blamed GSM-related sexual problems for the break-up of their marriages.

(Why a "sleep divorce" might be good for your relationship.)

The urinary problems associated with GSM are particularly concerning because of how frequently they can be misdiagnosed and go untreated. When health care professionals aren’t aware that GSM is behind a woman’s UTIs, women will continue to get infections. At the same time, doctors may assume symptoms of painful and frequent urination are UTIs and prescribe antibiotics when the problem is actually the irritation and dryness of urinary tissues.

“It’s the same symptom but might not be the same cause,” says Kingsberg.

The complications can be especially fraught as women continue to age. Decades of GSM can actually cause the outer genitals to fuse, potentially blocking the flow of urine and contributing to infection. “There are serious medical situations such as recurring urinary tract infections that can progress to sepsis,” says Streicher. “While this is a rarity, it’s not hyperbolic to say that women can die from GSM.”

Finding relief

Despite now having a more accurate name, GSM is still notoriously underdiagnosed. “And only a small fraction of women is treated, despite the availability of good therapies,” Faubion says. A recent study showed that only seven percent of menopausal women were offered medications that could help control symptoms.

The first step toward relief is to use over-the-counter vaginal moisturizers to keep vaginal tissues moist day to day, as well as lubricants to reduce friction and pain specifically during intercourse. Menopause specialists generally recommend using moisturizers every day (or up to every three days for some preparations) to lock in moisture, much like you would with face creams.

(Vitamin C, retinol, biotin? Here’s what your skin actually needs.)

However, some experts caution against water-based moisturizers and lubricants, which often contain ingredients that increase the product’s “osmolality”—meaning it pulls moisture out of vaginal cells and can even promote dryness, Streicher says. Silicone-based products, or a water-based lube with an osmolality rating of less than 380 may be better bets, research suggests.

“If someone’s only symptom is pain with penetrative sex, and if it's mild, then you can start with one of these,” says Streicher. “If that doesn't work, or if you're having urinary symptoms, then it's time to go the prescription route.”

Since loss of estrogen causes GSM symptoms, it is also the gold standard treatment when delivered locally—as a vaginal cream, tablet, suppository, or ring. It’s a safe choice for almost everyone since it doesn’t enter the bloodstream, Streicher says.

“Estrogen restores the more healthful bacteria in the vagina, and as a result, the vagina can defend itself from pathogens, as well as be healthy for any kind of sexual activity,” says Simon. Recent research in the Journal of Urology showed that women who regularly use vaginal estrogen for recurrent UTIs have significantly lower rates of sepsis and death.

The FDA has also approved the hormone DHEA in cream form and an oral tablet called ospemifene (Osphena) to treat GSM.

Women who have developed tight pelvic floor muscles because of painful sex and other vaginal symptoms can benefit from pelvic floor physical therapy and/or the use of vaginal dilators, Kingsberg says. Beyond these remedies, there are high-tech remedies like laser and radiofrequency treatments that purport to stimulate new tissue formation, as well, although data suggest they don’t do as much to relieve symptoms.

If your doctor seems clueless about GSM, it may be wise to look elsewhere for help, say experts. The Menopause Society has a database of certified menopause specialists, searchable by location. The ranks of the specialty have swelled from about a thousand a decade ago to 10,000 today, Kingsberg says, so there’s no need to suffer in silence and every reason to believe that things can get better.

Says Faubion, “The good news is that we have safe and effective therapies for women with GSM and with treatment, most women can look forward to complete resolution of symptoms.”