Health stories: Talking through cancer

Being diagnosed with cancer is often the most frightening experience of anyone’s life, which makes talking about it crucial to managing it.

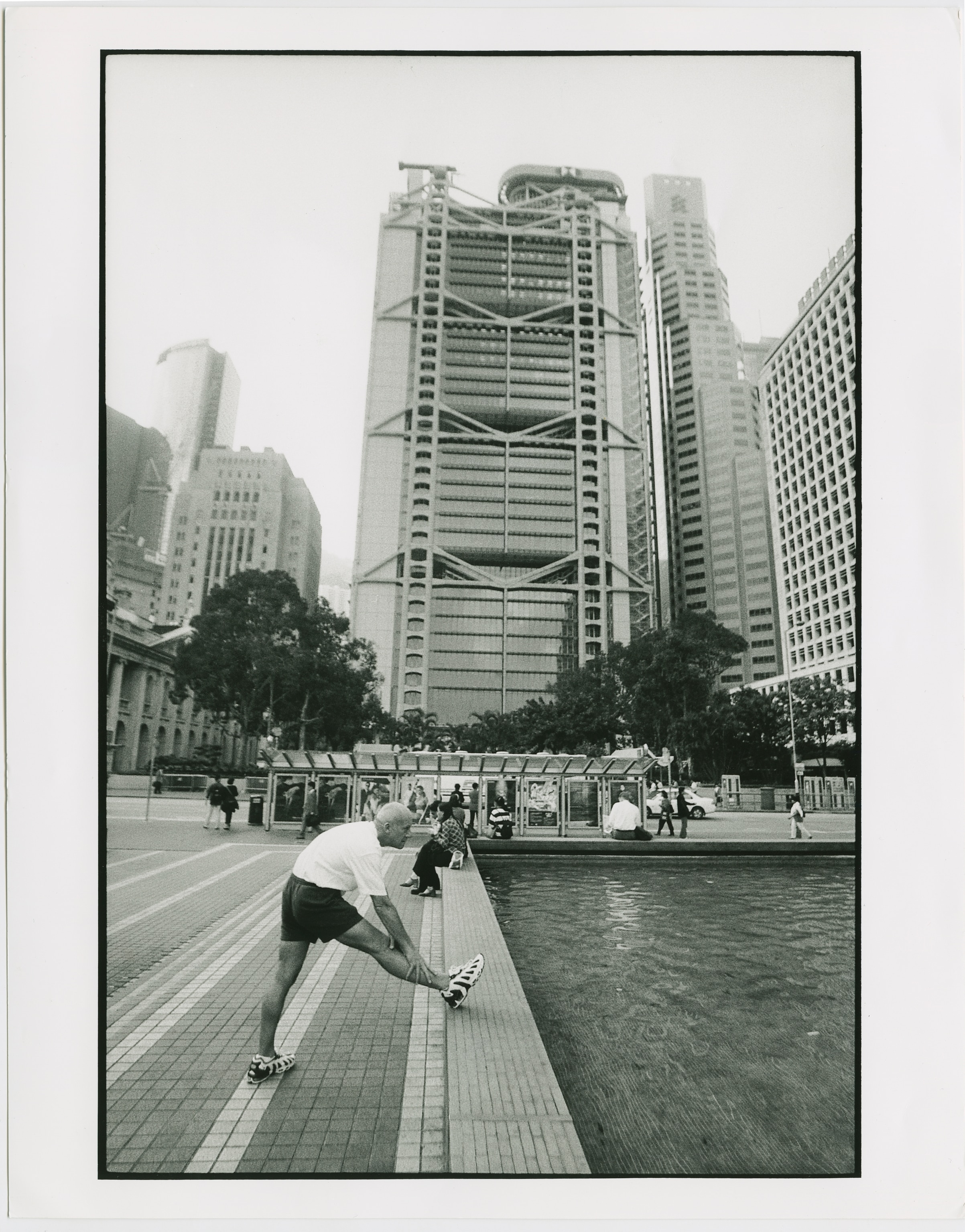

“Even though it rains the whole time in Manchester, the idea is very optimistic,” reflects Lord Norman Foster in an interview about his “outdoorsy” design for Maggie’s in Manchester. In 2013 the world-renowned architect, famous for such iconic buildings as London’s Wembley Stadium, Berlin’s Reichstag, and the Apple Park campus in California, took on a commission for Maggie’s, a “home away from home” for anyone dealing with cancer.

“I don’t think there is any question that if you are ill, beautiful buildings help,” he explains. “Research has shown that someone recovering with a nice view compared with someone facing the wall does far better.”

And this is something particularly close to Lord Foster: He was diagnosed with bowel cancer in 1999.

Cancer is one of the world’s most common serious illnesses and the second leading cause of death globally—one in six people die because of cancer. This generic term covers a large group of diseases that share the same feature—abnormal cells that rapidly reproduce and grow to invade other areas of the body and its organs. It’s a disease that can start and spread anywhere, with more than 200 different types of cancer. The most common include breast, lung, prostate, and colorectal cancers. This last, the bowel cancer that Lord Foster survived, is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide.

Thanks to ongoing research into early detection and treatment, survival rates for many types of cancer are improving. But there is still a stigma attached to talking about cancer, so much so that even speaking its name carries fearful connotations—the world has adopted euphemisms, including “the Big C” and “the C word”. It’s a powerful indicator of how reluctant we are to talk about cancer. We are fundamentally afraid of it, and we worry about not having the answers or the right words to face it. But the reality is that talking about our health, including and perhaps even especially cancer, helps. Global research on behalf of Bupa has shown that while half of us avoid addressing health concerns, most of us believe that talking about them can support our health.

It's a problem to which Lord Foster can relate. When his father was diagnosed with cancer “no-one discussed it.” And such silence can have a devastatingly negative impact. Not talking can bring deep uncertainty, fuelling feelings of helplessness and loneliness not only for a patient but for all those around them—family and friends who care and want to help.

“It’s the unknowns that create the agony, the upset, the anguish,” says Lord Foster. But he understands how hard it is to talk about cancer—he admits to being terrified and embarrassed and going into denial when first diagnosed. In fact, a quarter of people don’t talk about an illness because of embarrassment or stigma. However, Bupa research found that 41% of people who shared their health concerns felt less anxious, whereas 31% who didn’t, felt their health worsen.

That’s why it’s important to talk about our health. “People say, “How are you?” and you say, “I’m fine,” whether you’re feeling awful or 100 percent,” smiles Lord Foster. “It’s a social ritual.” But as social animals, in times of crisis talking can help us to release emotions, strengthen relationships, and improve our mental and physical health. Talking about a cancer diagnosis can help us to understand and take control of our feelings, leaving us feeling more connected, supported, reassured, and relieved. When, what, and with whom we share is a very personal decision. Often, we will confide in someone close to us, but it can be easier to talk to someone we don’t know or someone who has been through the same illness.

“When you become aware that they have a health issue and that connects in some way with one’s own past, then I think you’re more open to share, you want to reassure,” agrees Lord Foster, as part of Bupa's global Health Stories movement to encourage more people to talk about health. It brings genuine empathy and even inspiration, putting your illness in perspective and helping you to visualize a more positive future.

This is reflected in Lord Foster’s design for Maggie’s. “You can sit on the verandas in the rain surrounded by garden,” he explains. “The inside of the building is very cozy and intimate and feels like a home. It has natural light, a conservatory, and a kitchen table.” This all helps people relax and encourages them to talk. “Anything that can create a better environment is so important,” Lord Foster stresses.

This was powerfully brought home at Maggie’s opening, when Lord Foster met a lady whose husband had died of cancer. “She said they would come out of hospital after another terrible prognosis and drive around until they found an empty café to talk. Maggie’s gives you that space. It allows you to ask questions. You can engage with others.”

“I think back to the world of design and architecture,” says Lord Foster, “and one of the things we’re teaching is how to communicate.” Great buildings need to be more than aesthetic: they need to be functional—to facilitate their purpose. Maggie’s does this. “The best health and the best buildings, you take them for granted. It’s only when they start to malfunction that your attention is drawn to them.” And this underpins the importance of prevention. Around 30 to 50 percent of cancer cases could be prevented by tackling risk factors—diet, nutrition, and physical activity. But when the news is bad, positive talking, like positive architecture, can help. When asked how he’d respond to learning that someone had cancer, Lord Foster doesn’t hesitate. “I’d take them to one side and say, “You may be going through the same reactions that I went through. And it’s important that you know I’m still around.”

Find another story on the power of talking here.