Doctors are starting to take women’s pain more seriously

How scientists are trying to make in-office gynecological procedures a little more comfortable.

“You’re going to feel some pressure, followed by a pinch.” That’s what Delia Mendoza was told to expect when she had an endometrial biopsy in 2021 to evaluate her irregular bleeding and heavy periods.

“No pain meds were offered to me before, during, or after the procedure—and nothing prepared me for the pain I felt,” says Mendoza, then 38, a PR consultant in Los Angeles. “I was sobbing and shaking with pain. It literally felt like my insides were being ripped out,” she says. “I felt misled—it was way more than a pinch. It felt like the pain was totally discounted.”

In May, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists made headlines when it released new guidelines with a simple exhortation to health-care professionals to “not underestimate the pain” patients like Mendoza commonly experience during in-office gynecologic procedures and to provide them with “more autonomy over pain-control options.” The guidelines also lay out which pain medications have been shown to help.

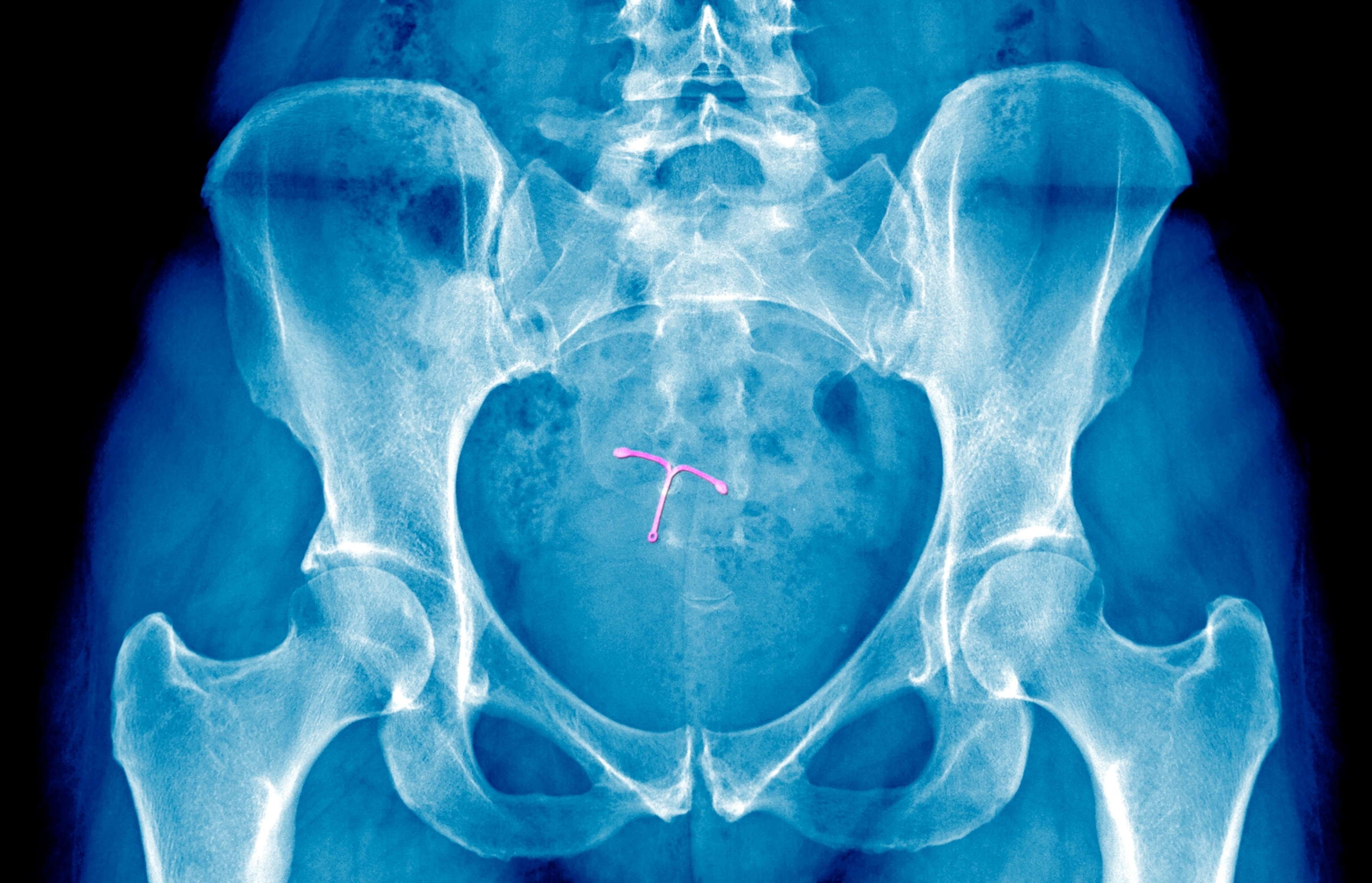

To many women, this felt long overdue but it’s part of a new effort to make women’s gynecologic procedures less painful. To that end, in recent years, there have been announcements about the development of smaller IUDs and smoother speculums for cervical exams, among other innovations promising a gentler experience at the doctor’s office.

Intense discomfort and pain with below-the-waist procedures are one reason women often put off seeing the doctor: A 2024 Harris Poll of more than 1,100 adult women in the U.S. found that 72 percent reported delaying a gynecology visit, with 54 percent saying it was because of fear or discomfort. And a study in a 2023 issue of the journal Obstetrics and Gynecology found that 97 percent of the top 100 TikTok videos tagged #IUD were related to the pain or side effects of IUD insertion.

“TikTok and social media videos told us loud and clear that the pain of these procedures is not acceptable,” says Eve Espey, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque.

There’s also “a growing body of evidence” to support talking about these issues “in a constructive way,” says Kristin Riley, one of the authors of the ACOG guidelines and a minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon at Penn State Health.

But is the future of women’s health really less painful? Here’s a look at some of the innovations that are on the horizon—and how much of a difference they are likely to make.

Better pain management

Just as not every woman is the same, not every pain medication is the same—and some may work better for certain people or certain procedures.

“The patient experience of pain is widely variable—for example, some patients will have a little cramping with an IUD insertion, whereas others will consider it the worst pain [they’ve] experienced,” says Tessa Madden, a professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive science at the Yale School of Medicine.

The idea behind the updated ACOG guidelines is to outline all the options available and encourage women and their doctors to think through their choices.

In the past, pain medications weren’t offered at all for some of the most common in-office gynecologic procedures.

However, as the new guidelines make clear, patients getting IUD insertions have options that include local anesthetics in the form of a lidocaine spray, lidocaine-prilocaine cream, or a paracervical lidocaine block (administered by injection).

For a cervical biopsy through colposcopy (a procedure in which the cervix is examined under magnification), practitioners can inject a local anesthetic and vasoconstrictor to reduce pain, or administer a lidocaine spray or injection. Patients also can take NSAIDs ahead of time.

For an endometrial biopsy like Mendoza experienced, the guidelines suggest that topical or injected anesthetics and/or NSAIDs like naproxen may help reduce pain. Intrauterine lidocaine may be especially helpful, according to a study published in January 2025. It compared the effectiveness of four pain medications—intrauterine lidocaine, an oral NSAID, a cervical lidocaine spray, and a paracervical block with prilocaine—among women having an endometrial biopsy and found that those who received the intrauterine lidocaine had significantly lower pain scores than those in the other groups.

The ACOG guidelines were released just this year so your doctor may not be offering these options yet. But women should know they are available and ask for them.

Will it help? That’s the million-dollar question—and the truth is, these options alone might not be enough to ease pain for everyone. “It’s hard to predict who’s going to experience pain,” Riley says—and women may be surprised by the level of pain they experience with a given procedure. “Sometimes people wonder if there’s something wrong with them that made it so painful,” Riley adds. Others might wonder if the doctor is bad at the procedure or if something went wrong.

That’s why the guidelines also recommend doctors provide an accurate description of what’s involved with a given procedure. “Women have a range of experiences—we can’t assume it’s not going to be painful,” says Louise King, a gynecologist and director of reproductive bioethics at the Harvard Medical School Center for Bioethics.

New speculum designs

Meanwhile, a slew of new instrument designs may contribute to reducing pain with certain gynecologic procedures. Among those getting a modern makeover are speculums—perhaps the most dreaded instruments in gynecology.

This device, which looks like a duck’s bill, stretches the vaginal walls open during a procedure. In the past it has typically been made of metal, which providers have warmed up as a modern standard of care.

“I tell medical students who work with me that the basic instruments I use every day in the operating room and in the office were created in the 1800s,” says Rachel Pope, an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine. “There’s been very little innovation despite huge advances in technology and other areas of medicine.”

In recent years, however, smaller, plastic vaginal speculums have become available, which experts say should cause less discomfort with Pap smears. “The smooth, plastic ones feel better for many people even though they’re cold,” says Pope. “We probably have been using speculums that are too large for people.”

Researchers are also trying to improve on the plastic speculum. A disposable five-petal design called the Bouquet Speculum has been cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Because it opens horizontally as well as vertically, it could provide clinicians with a more efficient and accurate way to perform Pap smears, with less discomfort for the patient.

Will it help? Because the new five-petal speculum hasn’t been widely studied, “it’s not ready for prime time,” Espey says. “Regarding the data that it’s more comfortable—the jury’s out on that. Speculums by their very nature are uncomfortable. I think it just looks more friendly.”

A softer brush for biopsies

Gynecologists are also looking forward to gaining new options for cervical biopsies, or collecting tissue from the cervical canal to test for cell abnormalities.

They’re intrigued by a fabric-based device (called fabric-based endocervical curettage) that claims to gently do the sampling. In addition to theoretically feeling softer against the cervix than the existing metal instruments, one study found that the fabric-based device seems to produce fewer inadequate specimens than the conventional approach.

Will it help? Though these newer designs have been available for several years, they aren’t widely used. “The dissemination of a new technique typically takes 16 or 17 years,” Espey says.

However, some clinicians are skeptical that the fabric-based device would make much of a difference.

“For biopsies, we should be offering pain blocks and sedation,” says Pope, who is also chief of female sexual medicine at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center. “Even if we get a better instrument, it’s still important to offer pain-management options.”

Smaller, more flexible IUDs

Smaller IUDs have already become available, which experts say make this form of birth control easier and less painful to insert through the opening of the cervix.

One such design is Kyleena, a hormonal IUD that can stay in place for five years—“it’s good for someone who’s never been pregnant,” says Pope. And there’s Skyla, another hormonal IUD that lasts for three years. “It has a significantly smaller stem [which] makes insertion less uncomfortable, but there are more irregular bleeding issues with it,” Espey says.

A new copper (hormone-free) IUD called Miudella that lasts three years was approved by the FDA in February 2025 but isn’t expected to become available in the U.S. until sometime in 2026. “We’re all anxiously awaiting it,” Espey says. “It has a shorter stem and a flexible frame so there’s likely to be less pain with insertion and less risk of expulsion. It’s specifically targeting women who haven’t had a baby.”

Will it help? The newest addition is bound to be a welcome option, given that IUD insertion can be especially painful for women who haven’t given birth.

Rebecca Bonanno, 50, discovered this in April 2025 when she had a traditional hormonal IUD inserted to treat the severe menstrual cramps she was experiencing from uterine fibroids. The nurse practitioner performing the IUD insertion didn’t prepare her for how painful it would be and had trouble getting Bonanno’s cervix to open sufficiently.

“It was some of the worst pain I’ve ever had. I felt at one point that I was going to pass out,” says Bonanno, a clinical social worker in Huntington, New York, who is married without kids. “I had taken ibuprofen ahead of time but it didn’t touch the pain I was in.” And the pain didn’t let up for four hours, even after the insertion had been completed.

What took so long—and what else can you do to ease pain?

There is a long, documented history of doctors minimizing or dismissing women’s pain, often due to gender bias in medicine, experts say.

“Historically, medicine has been very male-driven,” says Kim Hoover, an ob-gyn at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and a member of the ACOG clinical consensus committee. “Now, more female physicians are out there, giving voice to their patients.”

But there’s another reason it has taken so long to address women’s pain: money. Insurance reimbursement rates for office-based gynecologic procedures are lower than for office-based urology and dermatology procedures, according to a review in the February issue of the AMA Journal of Ethics. Gynecologists “don’t have the same resources to pay for ancillary staff to administer in-office anesthesia,” says King.

Cost will also likely be an obstacle with newer innovations, which are “expensive and not widely adopted by large health-care systems or clinics,” says Pope. “If there’s something new and there isn’t a huge demand for it, it doesn’t get brought in.”

Complicating matters, some of the research on pain management strategies has yielded conflicting results. With real-world experiences, there aren’t any guarantees, either. “When I had an IUD placed with a cervical block, it didn’t help at all,” says King. “It was exceedingly painful.”

Which is another reason experts say it’s smart to learn how to advocate for yourself.

If you need an in-office gynecologic procedure, discuss the details with your doctor ahead of time. “Ask your provider what’s going to happen and what you can expect, and what you can do for pain before the procedure,” advises Hoover. “Be your own advocate. If you’re scared or concerned about it, say 'I saw X on social media' or show the provider what you saw—and say 'I’m worried about this.'”

You can also ask directly: What options can you offer me for pain management?

If you know that you are highly sensitive to pain, mention that. And if you’ve had a tough time with other gynecologic procedures, if you have chronic pelvic pain, or you have experienced sexual trauma or abuse, tell your provider, Espey says. That way, extra consideration can be given to pain and anxiety you might experience.

Some doctors, including King, tell their patients they can take a benzodiazepine (such as Ativan) before the procedure but they will need to have someone to drive them home.

If your doctor can’t provide you with the level of pain relief you want or need, they may be able to book you into an outpatient surgery center or hospital operating room where you can have moderate sedation, Espey says. But in order for that to happen, you need to speak up.

After the off-the-charts pain she experienced during her endometrial biopsy, Mendoza has become more assertive with her doctors.

“In the future, I’m going to be 100 percent honest about my pain tolerance and demand to be prepared truthfully for how much pain I will experience with any procedure so I can be adequately prepared,” she says. “I feel like women’s pain is far too often ignored by medical professionals.” From now on, she’s going to make sure that her own pain is taken seriously.