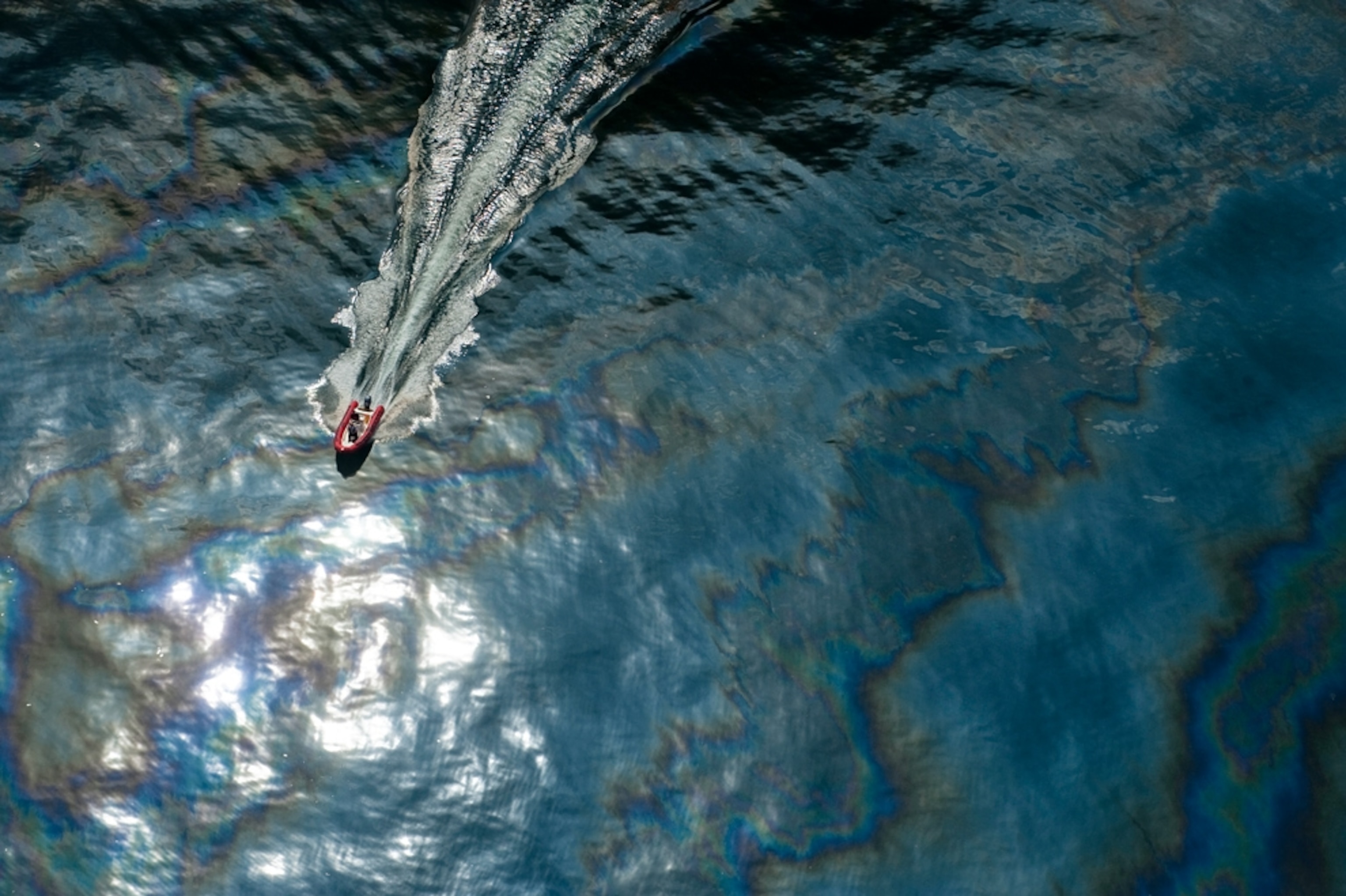

Gulf Spill Dispersants Surprisingly Long-lasting

Dispersant impacts on environment a major concern, expert says.

Massive amounts of chemical dispersants pumped into the Gulf of Mexico to break up the BP oil spill remained deep underwater for months, new research shows.

In an unprecedented tactic, U.S. authorities pumped some 800,000 gallons (3,028,000 liters) of dispersants directly into the flow of oil at the Deepwater Horizon wellhead, at about 4,000 and 5,000 feet (1,200 and 1,500 meters) deep. Most of the dispersant was applied in May and June, and the wellhead was capped in July.

No one knew how effectively the dispersants would work. But a new analysis shows the dispersants lingered for months pretty much right where they were put—trapped in subsurface plumes of oil and gas.

(See "Why the Gulf Oil Spill Isn't Going Away.")

"The dispersants got stuck in deep water layers around 3,000 feet [915 meters] and below," said study leader David Valentine, a microbial geochemist at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

"We were seeing it three months after the well had been capped. We found that all of that dispersant added at depth stayed in the deepwater plumes. Not only did it stay, but it didn't get rapidly biodegraded as many people had predicted.

"We don't know where exactly everything has gone since the last study, but dilution is continually decreasing the concentration," he added.

Dispersant Ingredients a Trade Secret

For the study, scientists tracked a key component of dispersant called dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate (DOSS) as the spill's deepwater plume of oil, natural gas, and dispersant moved southwesterly through the Gulf.

(See "Gulf Oil Spill Fight Turns to Chemicals.")

Some 640,000 pounds (290,000 kilograms) of DOSS was injected between April and July, a huge number made all the more daunting because the chemical comprises only ten percent of the total dispersant volume, according to the study, published online January 26 in the journal Environmental Science & Technology.

Likewise, these figures don't include an additional 1.4 million gallons (5.3 million liters) of dispersant that was dumped onto the ocean surface. Early experiments show, however, that deepwater dispersants never mixed with surface dispersants. In September DOSS was still present in significant concentrations even 200 miles (322 kilometers) from the wellhead.

Not surprisingly, subsurface concentrations of dispersant were highest at the wellhead and gradually declined with time and distance as Gulf waters mixed naturally.

According to Texas Tech University environmental toxicologist Ronald Kendall, the ingredients of the dispersants are trade secrets, so scientists didn't even know what was in the dispersants until after heavy use had begun.

"I think this continues to reveal how little we knew about the dispersants and how limited we were in predicting their fate in the environment," Kendall said.

"And we still have a huge lack of knowledge related to what their ecotoxicological consequences are going to be. This represents a still unfolding ecotoxicological experiment on a huge scale."

Jury Still Out on Dispersant Decision

The new data will also help scientists understand to what extent marine organisms such as coral and tuna were exposed to dispersants. Already, one preliminary study has shown deep-water coral has been severely affected.

(See "Giant Coral Die-Off Found—Gulf Spill 'Smoking Gun?'")

Kendall is concerned about deep-ocean animals. They can often be more sensitive to environmental disturbances, he said, because they've evolved more specialized survival skills.

"These organisms have developed capabilities to live under high pressures, with low oxygen levels, and with no sunlight. It's a more rigorous and perhaps less changing environment, and all of a sudden a wave of chemical dispersants comes by. What does that mean for the environment? I don't know. I really don't. But it concerns me significantly."

Of course oil carries its own environmental consequences, and these are perhaps worse when it's not dispersed.

That's why study leader Valentine called the tough decision to use enormous quantities of chemical dispersants at the wellhead an uncertain choice between "bad" and "worse."

"I think the jury is still out on whether or not it was the best decision," he said.