In Rwanda, Reconciliation Is Hard Won

On the eve of the 20th anniversary of the genocide, villagers in the countryside struggle to forgive the unforgivable.

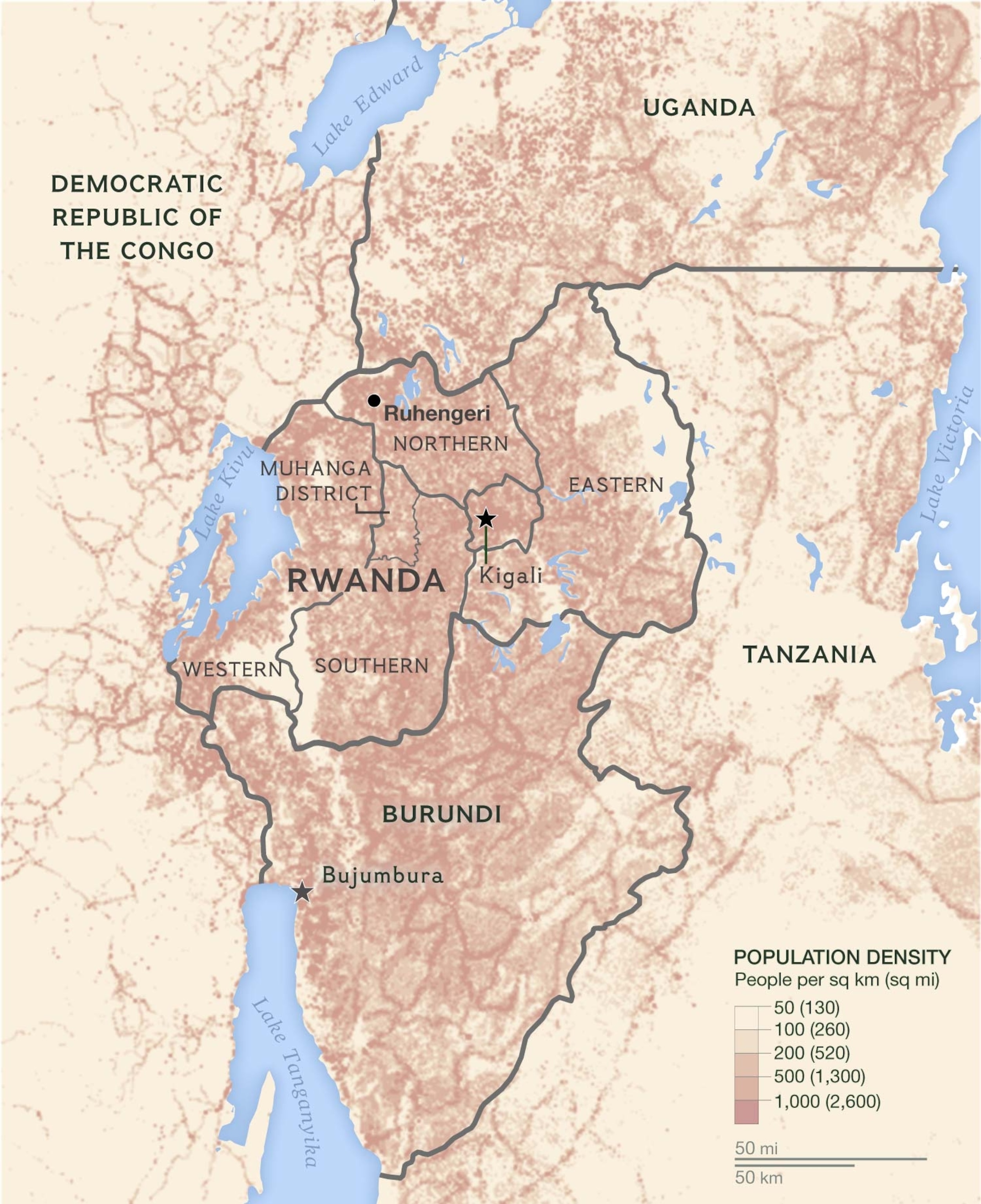

The Tutsi residents of the village of Jabiro, which occupies the spine of a hill in the Muhanga District in Rwanda’s southwest, had heard rumors about bands of men coming from the capital, Kigali. They’d known of the Hutu-only rallies held in the district. But they didn’t grasp the reality of what was happening until the third week of April 1994, when they began hearing screams coming from the villages on neighboring hills. Black smoke rose into the sky above nearby farms. Then the screams grew louder, the smoke thicker.

On April 23, the killers arrived—buses full of men. At first they claimed they were looking for fighters with the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), the Tutsi-led rebel group that wanted to overthrow the Hutu-led government. Soon enough it was clear they were just looking for Tutsi. They were Interahamwe, the citizen militias that had been whipped into a frenzy by propagandists and officials and Hutu Power anthems on the radio, and then armed by the government. They recruited Hutu from around Jabiro. Late in the day the Interahamwe and their local accomplices set up roadblocks at the foot of the hill.

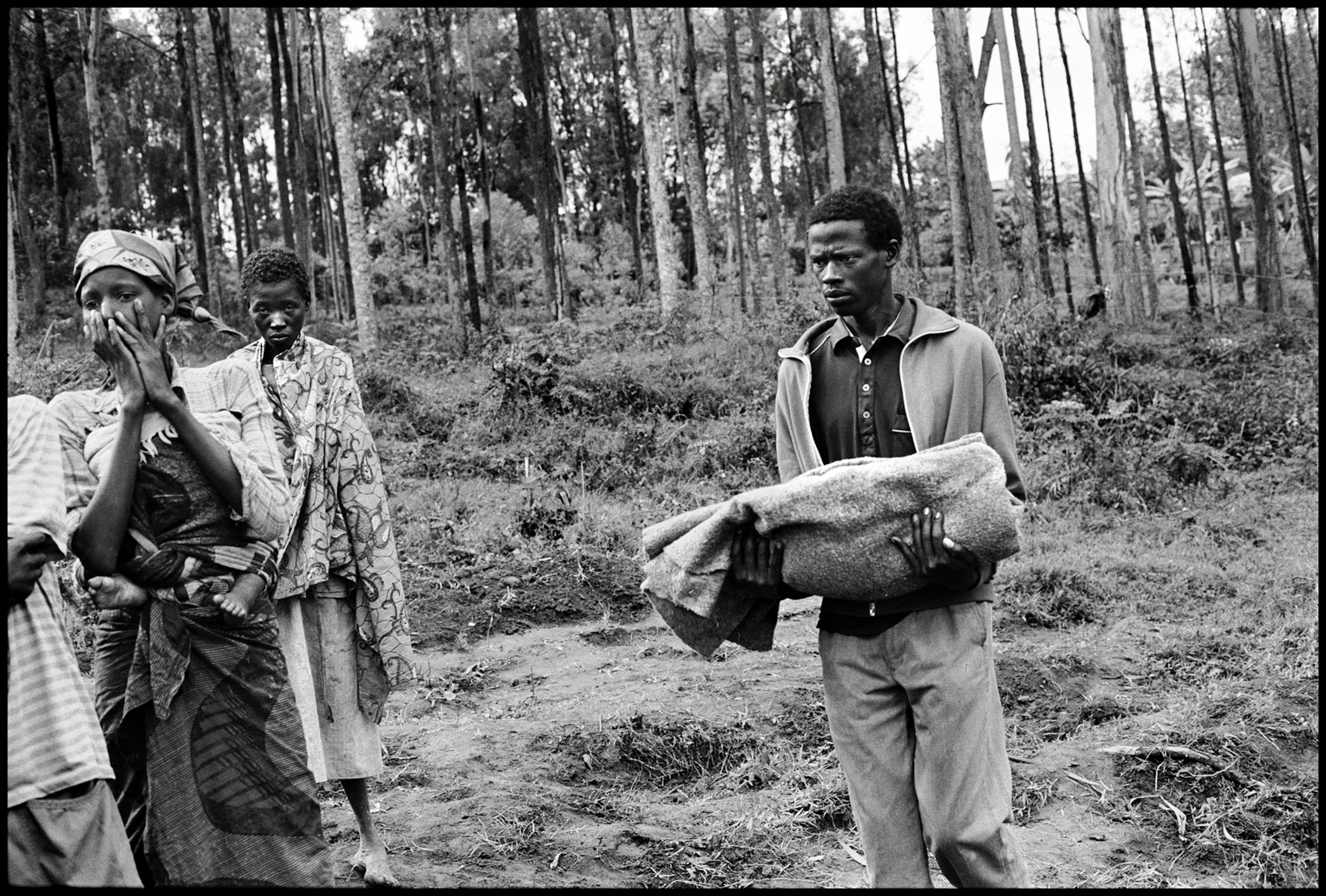

As villagers returned from the vegetable fields, and children walked back from school, they were stopped. Their identity papers were demanded. If they were found to be Tutsi, or of mixed Tutsi and Hutu heritage, they were almost certainly mutilated and then murdered. First out of view among the trees but, before long, in the road. The killers slashed their heads and bodies with machetes. They cut off arms and legs, hacked away with hand scythes and knives. They smashed skulls with clubs, gouged and impaled torsos and appendages with metal construction picks and sharpened sticks. This went on for hours, days, as the corpses piled up on the roadside.

By May, there were no more living Tutsi in Jabiro. The lucky ones had escaped. Most had been murdered. By July, three out of four Rwandan Tutsi no longer existed.

Nineteen years, ten months, and three weeks later, residents of Jabiro were thinking about that week in April. Now, they were sitting patiently in a village community center. Outside was a typically magnificent Rwandan landscape of terraced hillsides and electric-green banana plantations. Survivors from the minority Tutsi ethnicity were there, along with their children and grandchildren, and so too were some of the local men, from the majority Hutu, who had attempted to kill them. They had all gathered to discuss with me the legacy of the genocide and to consider, once again, the ways in which their lives—and the life of their country—had changed in its aftermath.

Their expressions were calm, their voices steady. This was familiar psychological territory. The people of Jabiro, particularly the older ones, had thought about the genocide countless times on their own, of course. But when not doing that, they’d thought about it by official decree. The journalist Philip Gourevitch observed of the Rwandan genocide that “the horror of it—the idiocy, the waste, the sheer wrongness—remains uncircumscribable,” and it always will remain so. But circumscribe the horror is precisely what Rwandans have been asked to do for two decades now. Most of the adults in the community center had sat through gacacas, the local trials wherein more than 100,000 genocidaires confessed to their crimes and submitted themselves to the judgment of their neighbors. They had taken part in countless meetings. Down the road from the community center was the district’s official genocide memorial, the most impressive and best maintained building for miles around. In coffins and simple display cases are the bones and skulls of their relatives.

I asked them to tell me how, exactly, Jabiro came back together after the genocide. It was easy to talk about forgiveness. But how did they actually do it?

An old man in a corduroy blazer several sizes too large for him and pants smeared with dirt from the morning’s fieldwork stood up. “We’re living together,” he said. “There are no problems between us.” That was all.

Another man rose and elaborated. He explained that before 1994 Jabiro had been known for its harmony. Tutsi and Hutu intermarried, worked together, got on well. And it was true that, after the genocide and the years of civil war that coincided with and followed it, everyone was afraid of each other. “But we already knew how to live together. So, coming back together, we remembered how we used to live.”

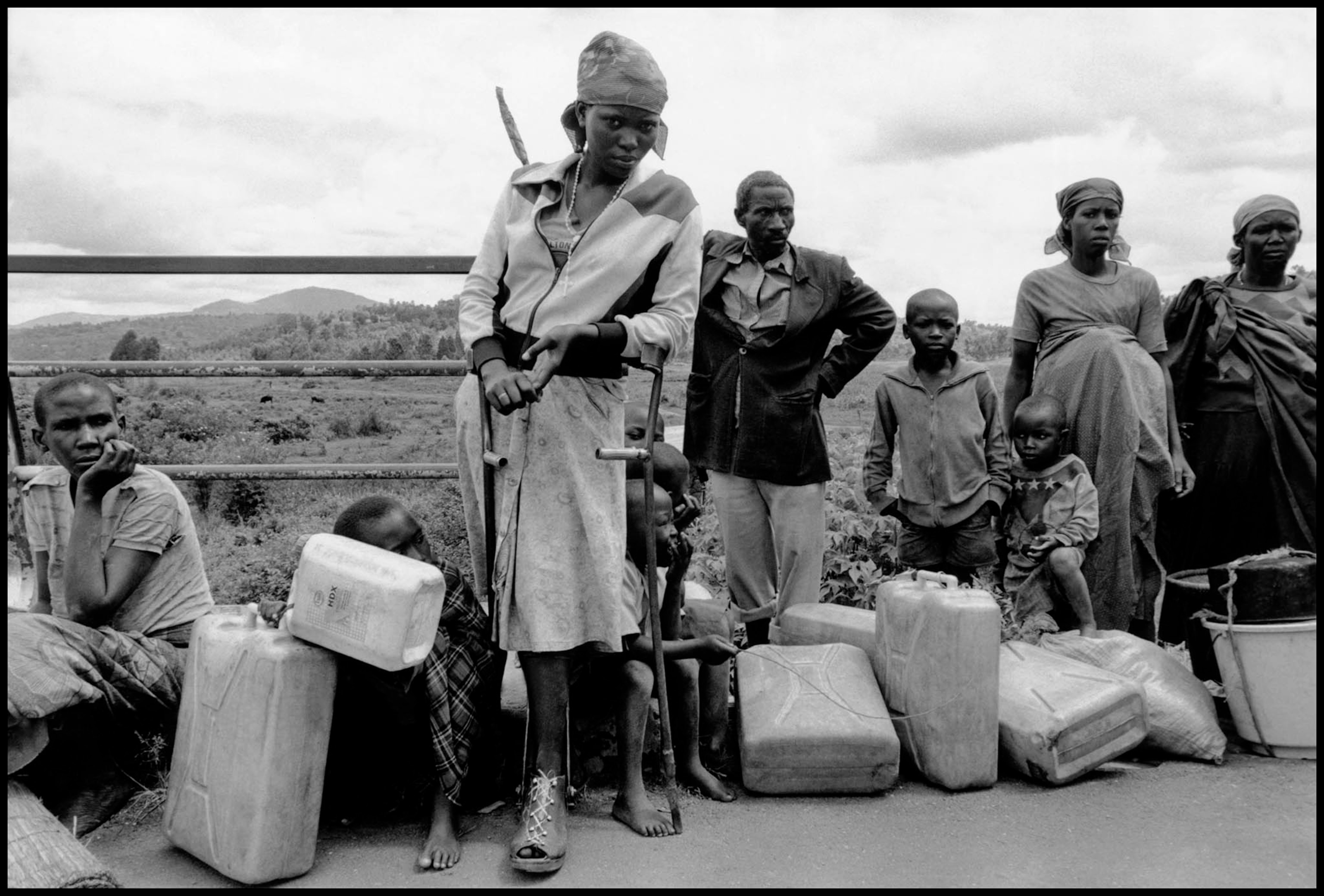

The stories became more personal. A man recounted returning to Jabiro late in 1994. When he arrived in the village, after days of walking, there was nothing left. Livestock had been stolen, possessions looted. The genocidaires had burned down Tutsi homes, and the RPF had burned down Hutu homes. He found his Hutu neighbors living in squalor. They were all too desperate to dwell on their differences. They had no choice but to work together, he said.

“When we returned, we found our banana plantation was destroyed,” an old woman said. I had spoken with this woman before the meeting and knew that both of her sons, her son-in-law, and her sister-in-law had died in the genocide and the fighting that followed. As I’d sat beside her, she'd counted 15 murdered members of her family. She wasn’t sure she’d remembered everyone. “Hutu neighbors fed us,” she told the group. “They brought us bananas and juice.” People who had stolen their furniture returned it and asked for forgiveness. “When they asked to be forgiven, we could, because we could see it was coming from their hearts. It wasn’t hard to forgive them.”

Perhaps they said these things because they wanted to tell a journalist what they thought he wanted to hear. Perhaps they said them because they felt they should. Or perhaps they said them because they still found the truth of what they were saying so astounding. It was impossible for me to know, not least because what they were saying was, I believe, true, and was, unquestionably, astounding. Uncircumscribably astounding.

“We Think About the Future”

The plain cement slab outside the memorial near Jabiro reads “Never Again.” The official motto of remembrance in Rwanda, its implication is that Rwandans will never again allow for the historical circumstances that led to the genocide. A natural presumption is that this disallowance requires remembering what those circumstances were. Yet Rwanda also insists, to itself and to the outside world, that it no longer brooks the backward notions that led to the genocide—in particular, the notion of ethnicity, which every Rwandan schoolchild now knows is a “construct.” (A word they learn in English. Thanks in part to Rwandan animosity toward France, which armed and protected Hutu genocidaires, its language is being phased out of the once Francophone nation.)

The government goes to great lengths to portray Rwanda not just as a recovered post-conflict society but as a purified one, a post-ethnic one. Its message seems to be that while the genocide ought never to be forgotten, most other elements of the country’s past can and must be. “We don’t think about ethnicity,” a woman told me at the community center. “We don’t think about history anymore. We think about the future.”

This proposition, in its nobility and its naïveté, defines Rwanda today in subtle ways—people are frightened of not espousing the official line, and if they say the words “Hutu” or “Tutsi,” it’s often sotto voce, with a glance around the room—and in overt ones. President Paul Kagame, a Tutsi and the former commander of the RPF, has recast his country’s image from one of cataclysmic wasteland to a nation on the indomitable rise. And in certain aspects the image reflects reality. Rwanda is easily the safest, least corrupt, best groomed nation in the region. Kagame has attempted, with a great deal of success, to collectivize the countryside, and he’s endeavoring to make Kigali a regional business hub, redistricting it to accommodate office blocs and expensive homes, privatizing utilities, inviting in multinational corporations. There are streets in the capital where it’s easier to find a Chinese businessman than a Rwandan one.

In other ways the image is a fantasy, and a pernicious one. Kagame’s government emits prodigious amounts of propaganda, intimidates or controls the press, discourages freedom of assembly, and jails people for espousing “sectarianism” or “genocide ideology.” For every new shopping mall that goes up in Kigali, another informal settlement of Rwandans forced to the margins by bulldozers and high rents materializes on a hillside just out of view of the high-rises. For every foreign executive who moves in, another opposition figure is arrested or forced out, or assassinated. Even Kagame’s supporters openly admit that the country’s press is mo kwasha na reta—in the armpit of the state.

For every Tutsi who marvels at the country’s turnaround, there are several Hutu who attest to being excluded from it. In Ruhengeri, the scene of attacks by the Rwandan Patriotic Front before the genocide and of massacres of Hutu civilians after it, I met a woman whose husband and children were all killed during the intambara, or war, as most Rwandans refer to the period of continuous violence between 1990 and 1998. (The Kinyarwandan word jenosidi is used less often.) They were shot in front of her when the RPF invaded their refugee camp in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, she said. She survived by playing dead beneath the body of her son-in-law.

She could not speak publicly about her experience, she said, or ask for the reparations that some Tutsi survivors received, because the government didn’t consider her suffering valid. Only Tutsi suffering mattered. It was pointed out to me that the official English name for the Rwandan genocide, in which many Hutu and people of mixed descent also died, is the “genocide against the Tutsi.”

A friend of hers told me that the Kagame government had taken to urging Hutu around Ruhengeri—including, he said, Hutu who had opposed the killing of Tutsi and who had nothing to do with the genocide—to publicly atone. When I asked, “Atone for what?” he explained, “For being Hutu.” He went on to say that if things don’t change, another revolution will come. “And this time it will be worse.” One hears this often in places like Ruhengeri.

A Citizen’s Duty

In the community center, I spoke with young people for whom the genocide is, as one boy put it, “just a story.” Another boy told me, “They killed each other. Then they came together.” And another: “What the killers did was not their own idea, but the government’s. After the bad government, we were lucky to get a better one that taught people not to hate each other.”

My translator, who is in her mid-20s, told me that she tries never to think or talk about the genocide, in which her father was killed. Her fiancé is an orphan of the violence, and they’ve agreed not to discuss their pasts. “I don’t ask him about it,” she said, “and he doesn’t ask me.” She said that most of her friends act the same way.

Young people have adopted the official version of events, or ignore the genocide entirely, out of expediency, one suspects, if nothing else. They have more pressing concerns on their minds. In villages like Jabiro, the problems that have plagued rural Rwanda since it became an independent nation, in 1962, persist. While the local genocide memorial is manned by a full-time staff, a nearby secondary school sits half built and unattended. Not that it would matter—most of these kids, who live in sustained, when not grinding, poverty, have to work on the land much of the day. Even if they could study, there are few jobs to be had other than in agriculture. And in that too their prospects are few. Rwanda is the most densely populated country in Africa, and its land is almost entirely spoken for. Except for coffee and tea, most of the crops it yields go to supporting—barely—the people who work it.

At the end of the meeting, a man at the back of the room stood up. He was a Hutu, a onetime genocidaire. He explained that in early 1994, people with the Hutu Power movement began holding youth rallies near Jabiro. He was 14 at the time, and his brothers brought him to the rallies. They were as much social events as political ones, with music and dancing. “It was fun,” he said. At one rally he attended, a speaker exhorted the boys “to find the Tutsi. They are the enemies of this country. You must find them and eliminate them.”

On April 23, his brothers and friends went to man a roadblock, and he went with them. “I thought it was a citizen’s duty.” He watched as his brothers killed Tutsi. At this point, the man stopped speaking. Everyone in the room but me knew what had happened next.

“And did you kill?” I asked him.

He smirked bashfully. “At these roadblocks, if my friends killed someone, I could help.”

“So you cut them with your small machete?” a woman said. The room laughed. The man looked down.

Before he could go on, another man stood up. He explained that he was a survivor. More than that, he was the survivor who had been appointed by his neighbors to gather evidence and take testimonies for the gacaca trials that were held in this part of Muhanga in the mid-2000s. That’s when he’d met the Hutu man who’d been speaking. He had already spent a decade in prison for his crimes. The Hutu man agreed to appear at the gacaca, where his surviving neighbors sat in judgment of him. When the trial was finished, they decided he’d been punished enough. Released from prison, he moved back to Jabiro.

“People from outside the village organized the killing. Local boys like him weren’t responsible,” the survivor said. He and the Hutu man were good friends now, he added. “We have no problems with each other.”

The Hutu man agreed. “I think they’ve really forgiven me. The people I hurt, I share with them. We drink beer together. We live together. They’ve forgiven me.”

Afterward, I asked my translator if she believed that the survivors of Jabiro had really forgiven him. Her answer distilled a complex ambivalence about the legacy of the genocide.

“For me, they don’t really mean what they say. But they have to say it. There is no other option.” She thought about this. “It’s not that they have to say it. It’s the right thing to do. There is no other option than forgiveness. What else could they have done?”

“You cannot forgive such things,” she then said. “You just try to forget and lead another life.”

James Verini is a writer based in Africa and a fellow at the Schuster Institute for Investigative Journalism. He wrote about UN peacekeepers’ military intervention in Congo for nationalgeographic.com and about the Nigerian Islamist group Boko Haram in the November issue of National Geographic.