How Northern Nigeria's Violent History Explains Boko Haram

Long before this extremist group arose, other radicals terrorized the region, British former administrator says.

In the northern Nigerian town of Gombe, I became a registered alcoholic at the age of 22.

The year was 1957, and I was starting out as a district officer (the last to be recruited by the British government for service in northern Nigeria) just three years before the country won its independence.

The only way I could enjoy a "drink" in Gombe—a sleepy mud-brick township, laid out by the British in the 1920s, where Islamic laws were in force—was to issue myself an "addict's license." That document allowed me to obtain liquor from the "pagan" city of Jos, 175 miles (280 kilometers) away.

In my administrative capacity, I also had the authority to issue addict's licenses to the 12 other expatriate Europeans who lived in Gombe. I doubt many other towns in the world can claim the distinction of having their entire expatriate community registered as alcoholics.

I lived in a circular, thatched mud house and rode to work on my horse, which I hitched to a rail outside my office.

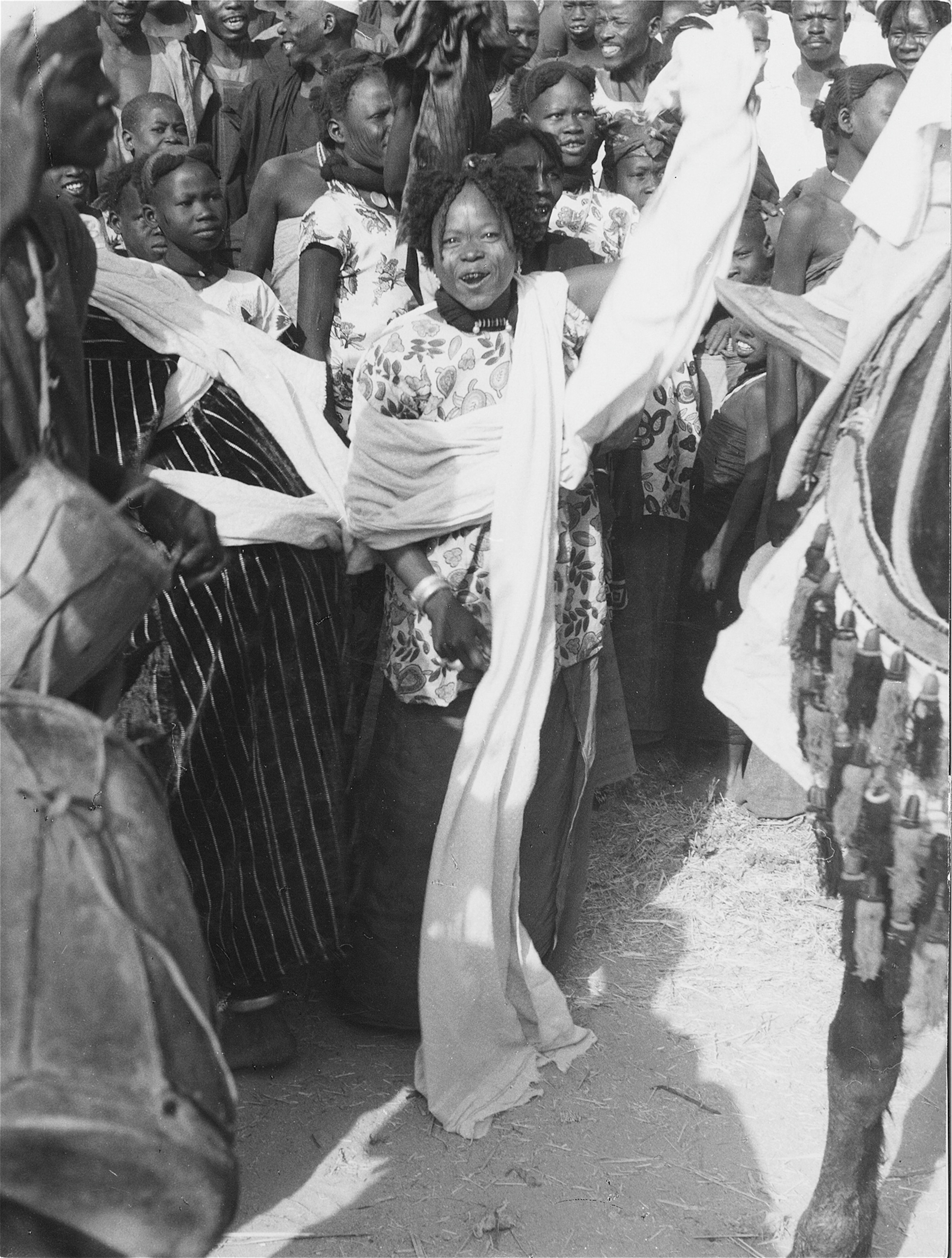

Gombe was essentially a happy place, presided over by a benign and astute Muslim emir of the Fulani tribe and a team of enlightened councillors. Apart from the odd dispute over a woman or land, there was little violence. Gambling was frowned on, but a blind eye was turned toward the drumming and dancing that in a pre-television age carried on throughout the year, except during the month of Ramadan.

But today Gombe is on the front lines of the obscene and bloody battle waged by Boko Haram to impose an extreme interpretation of Islam on the whole of northern Nigeria.

How has it come to pass that 55 years after Nigeria's independence, peaceful towns are being terrorized, attracting suicide bombers and an invading army of fundamentalist Islamists?

Boko Haram seeks to impose an extreme interpretation of Islam on the whole of northern Nigeria.

The answers lie in Nigeria's northeasternmost state, Borno—a 27,000-square-mile (70,000-square-kilometer) territory south and west of Lake Chad whose prominent inhabitants are the Muslim Kanuri tribe and where radical dissent led by brutal, fanatical men goes back well over a century.

In one burst of violence last month, Boko Haram attacked Gombe and Dadin Kowa, another sleepy town in my former administrative orbit, on the banks of the Gongola River.

Boko Haram invaded Dadin Kowa, which translates as "tranquility for everybody," in 30-some Toyota HiLux vehicles from Borno State to the east, setting fire to houses and government offices.

In Gombe, 60 miles (95 kilometers) to the south, the Nigerian army repelled the attack and called in the air force, which strafed and bombed the militant Islamists. There were numerous casualties on both sides—possibly as many as 50—but the exact number of dead has not been reported.

In northern Nigeria, radical dissent led by brutal, fanatical men goes back well over a century.

The kidnapping of 276 schoolgirls in Borno State in 2014 caught the world’s attention, yet that horror was only one of more than 800 Boko Haram attacks in the preceding four years. According to Human Rights Watch, some 6,000 civilians have died at the hands of Boko Haram since 2009, more than 2,500 of them last year alone.

I still have a strong personal link to these troubled areas. One town in Borno I knew, Kukawa, was my jumping-off point in October 2001 for a trek that took me on a 1,500-mile (2,400-kilometer), three-and-a-half-month journey by camel across the Sahara to Tripoli, in Libya. It's saddening to realize that this trek would be impossible to undertake today.

The Kanuri Empire

After my time in Gombe, I was posted to Mubi 145 miles east (233 kilometers) on the border between Nigeria and Cameroon. One of my main tasks was to follow the old maps and confirm the international border between Nigeria and Cameroon just prior to independence. (See "Geography in the News: Nigeria's Boko Haram Terrorists.")

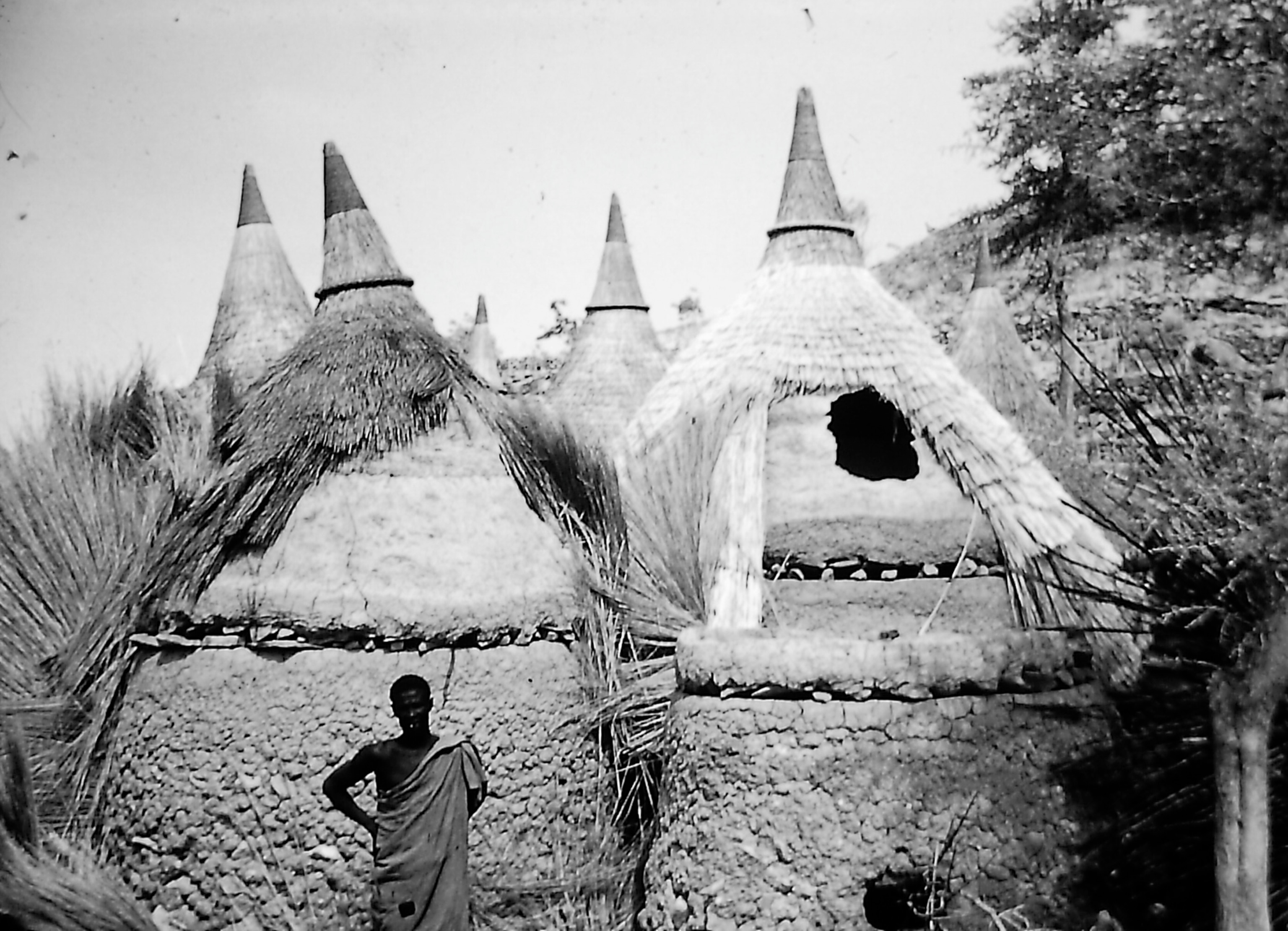

This involved walking 170 miles (275 kilometers) along the top of the Mandara Mountains—great bosses of granite sticking more than 3,000 feet (915 meters) into the air, strewn with rounded boulders the size of houses and stretching between Lake Chad in the far northeast of Nigeria to just beyond Yola in the south.

In precolonial times the mountains formed a central backbone in the vast Kanuri tribal empire, which extended eastward into today's Cameroon and Chad and north to the Fezzan, in southwestern Libya.

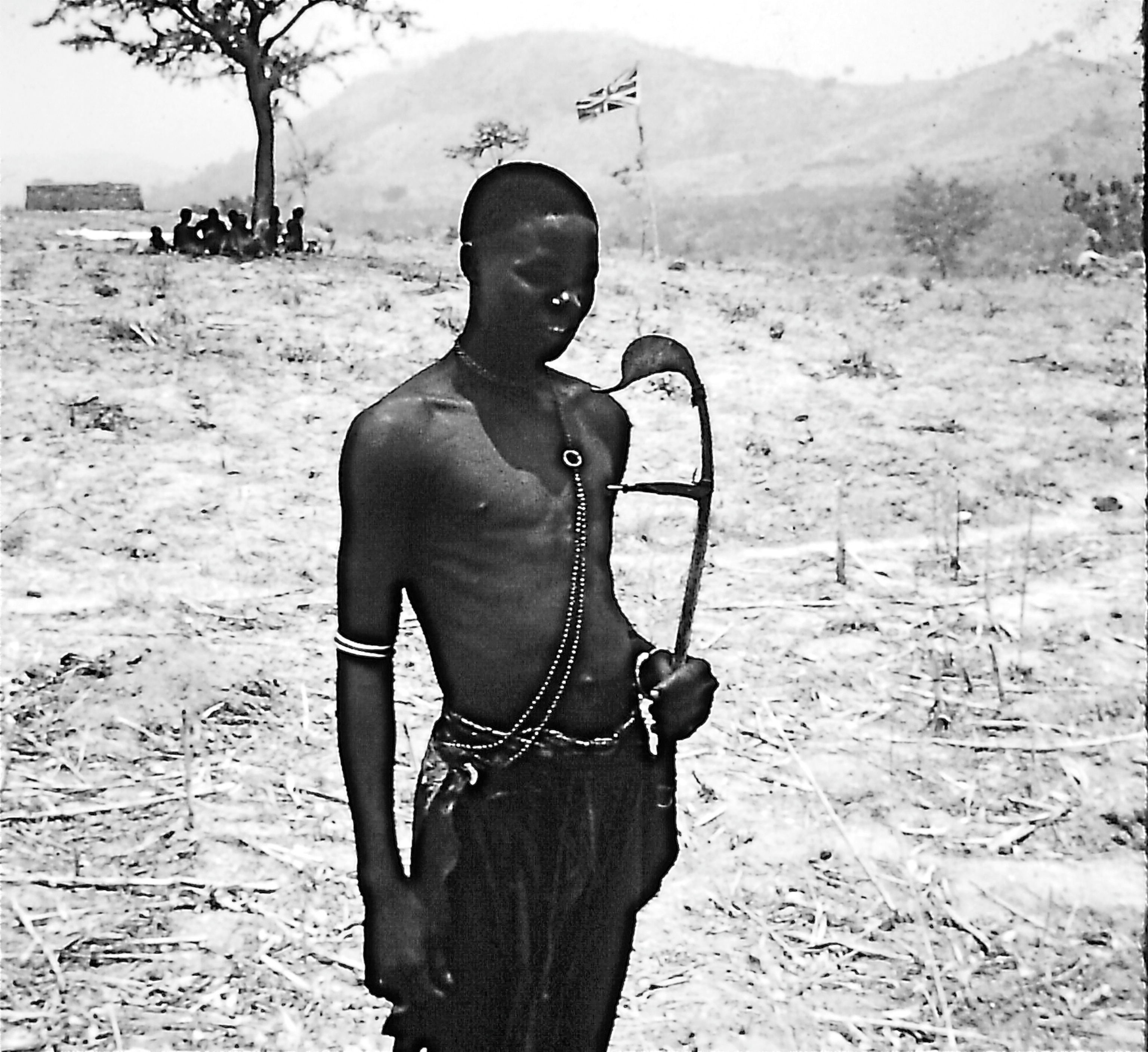

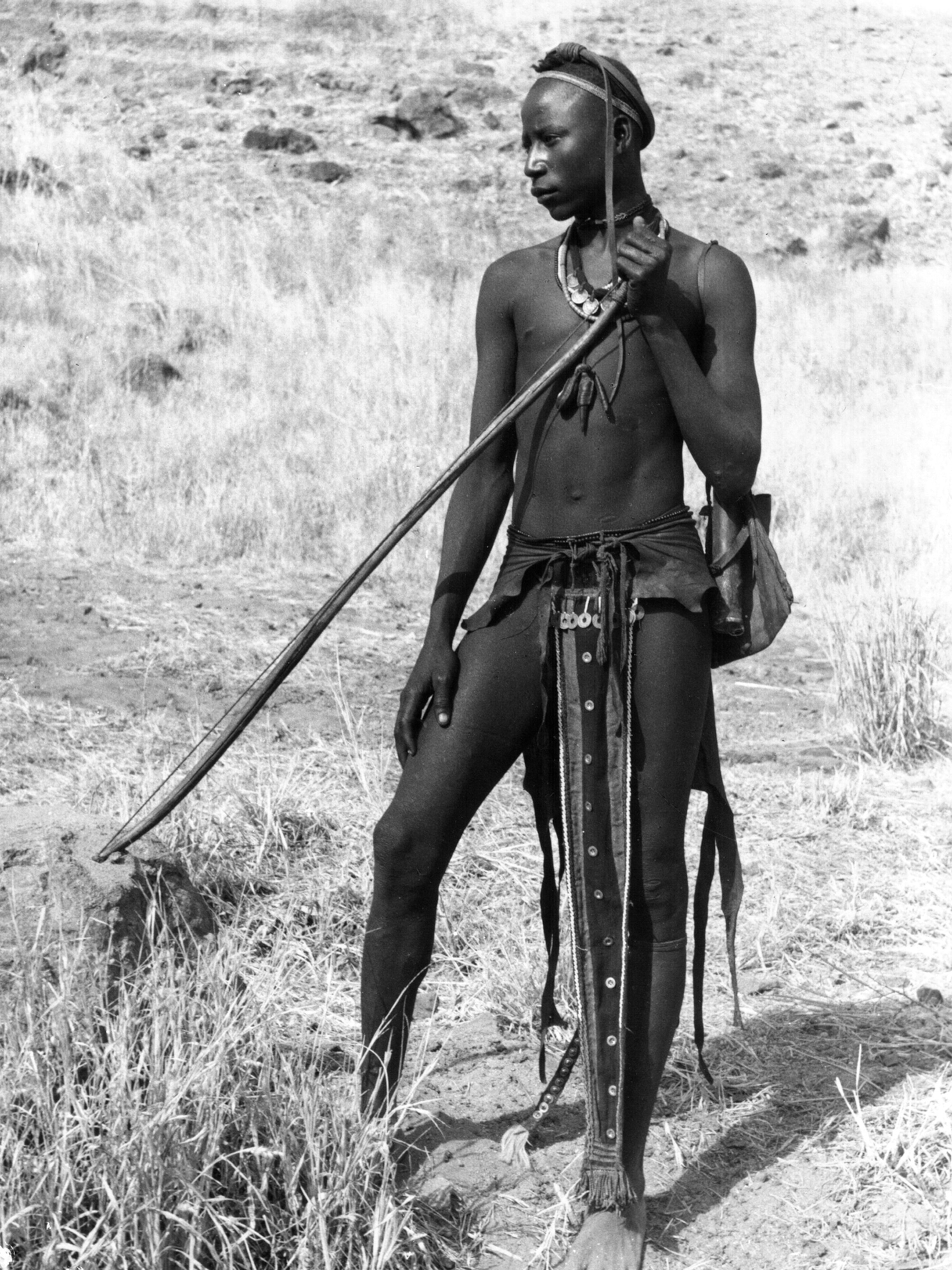

For centuries the Marghi, Hithe, Gwoza, Fali, and Matakam tribes—some of the wildest in Nigeria—had secured this mountainous fortress, fending off raids by mounted Muslim Kanuri slavers from Borno.

The tribesmen developed a deadly throwing knife, which spun through the air and sliced through the tendons of the raiders' horses.

Christians are the targets of forced conversion to Islam by the followers of Boko Haram.

In 1900, the British and the Fulani emirs agreed to establish the Protectorate of Northern Nigeria. The north was divided into provinces, one of which, Borno, was excised from the former Kanuri-inhabited Borno Empire. The agreement stated that Christian missionaries would be allowed to proselytize only among pagan tribes—not Muslims.

When I traversed the Mandara Mountains, about 30 percent of the people I encountered were Christians, 65 percent pagans, and 5 percent Muslims.

But since independence, missionizing has proceeded apace. Today nearly all the inhabitants are Christians, and they—especially the youth—are the targets of forced conversion to Islam by the followers of Boko Haram.

But even these conversions aren't entirely new. In 1964, the northern Nigerian government sent "Islamic missionaries" to forcibly circumcise and convert pagan tribesmen to the Muslim faith.

Today Boko Haram insurgents—headquartered in the town of Gwoza—are in complete control of the Mandara Mountains, where they've driven out and slaughtered tribespeople and forced others to adopt Islam.

These new killers didn't come on horseback but in armored cars, with ample supplies of sophisticated modern military equipment. The throwing knives were obsolete.

History Repeats

Boko Haram's form of violent dissent, which is particularly horrific, has an exact historical precedent 125 years ago in precisely the same part of what is now Nigeria and Cameroon.

In 1893, a renegade Islamic fanatic, Rabih Fadi Allah, invaded the region from Darfur, in western Sudan.

Rabih had fallen out with the Islamic reformer and self-proclaimed al-Mahdi, or holy man, Muhammad Ahmad, whose presence on Earth was thought to presage the end of the world and whose troops in 1885 killed the British general known as Gordon of Khartoum.

Rabih's horde of Islamic fighters swept in on horseback, beheading, looting, and enslaving in the name of Allah in a manner similar to Boko Haram today.

Nothing has been remembered more faithfully about Rabih than his violent temper, a passion that could be aroused for no apparent reason and not infrequently led to his inflicting savage beatings with his sword or killing people either by slitting their throats or cutting off their heads.

Rabih's favorite curse was Allah rektar rasak—may God cut off your head.

Abubakar Shekau, the self-proclaimed leader of Boko Haram, is said to be a fearless loner, a complex and paradoxical man, part-theologian, part-gangster.

Since he assumed the insurgency's leadership in 2009, after the death of Mohammed Yusuf, the movement's founder, Boko Haram has become more radical. Abubakar Shekau has carried out even more appalling atrocities than his predecessor.

He achieved savage notoriety in a video clip that showed him laughing as he admitted having abducted more than 200 Christian schoolgirls, mainly of the Kibaku tribe, in April 2014.

"I abducted your girls," he jeered. "I will sell them in the market, by Allah. I will sell them off and marry them off."

The two men appear to be similar kinds of fanatical, psychopathic leaders with a shared appetite for enslavement and murder.

One habit of Rabih's has not as yet been imitated by Abubakar Shekau: Known as "Rabih's mark," it was his way of defining ownership of all his slaves, followers, and subject communities. The marks varied—three small cuts on either cheek, three lines at the corner of the mouth, or a notched cross on the face forming an enormous raised scar.

In 1893, Rabih destroyed the Kanuri shehu (emir) of Borno's capital in Kukawa, killing more than 3,000 people and enslaving 3,800.

Rabih established his capital in Dikwa, 80 miles southeast of Kukawa, where his arbitrary rule was conducted in a sea of blood and horror. The remains of his house can still be seen today.

The parallel with Boko Haram is compelling. Kukawa is only 23 miles (37 kilometers) from Baga and a nearby town, where this year, on January 3, Abubakar Shekau's followers are alleged to have killed 300 people or more and destroyed 3,000 houses.

Abubakar Shekau established Boko Haram's Gwoza headquarters a hundred miles (160 kilometers) south of Dikwa, killing the incumbent emir of Gwoza in the process.

Rabih was finally killed on April 22, 1900, in a battle with the French, and the illustrious Borno Empire was divided among the French, Germans, and British.

Abubakar Shekau is still at large.

Hamman Yaji: A Ruthless Slaver

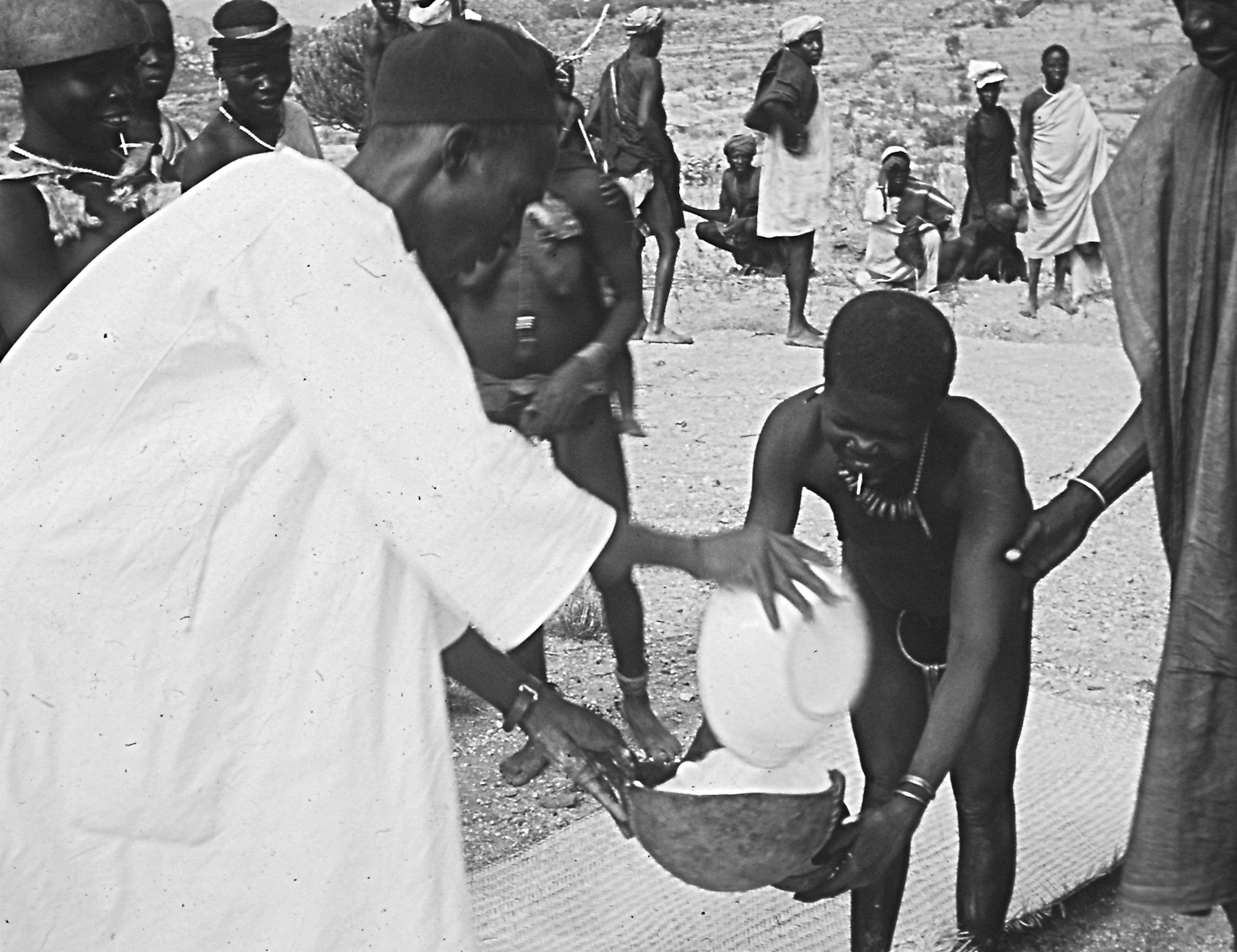

Malam Risku, of the Marghi tribe, was chief of the town of Madagali and a good friend when I was in northern Nigeria. A convert to Christianity, as a boy he'd been carried over the mountains to escape the depredations of an Islamic slave raider, the notorious Fulani tribesman Hamman Yaji.

Hamman Yaji recorded his activities in a diary in Arabic script:

1913, May 12: I sent my soldiers to Sukur, and they destroyed the house of the arnardo [the pagan chieftain] and took a horse and seven slave girls and burned the house.

1917, August 16: I sent Fad-el-Allah with his men to raid Sukur. They captured 80 slaves, of whom I gave away 40. We killed 27 men and women and 17 children.

An eyewitness account relates that "on one raid, Hamman Yaji's soldiers cut off the heads of the dead pagans in front of the chief of Sukur's house, threw them into a hole in the ground, set them alight, and cooked their food over the flames."

The wives of dead Sukur men were reported as being ordered to come forward and collect their husband's heads in a calabash. Children were said to have had wire hammered through their ears and jaws by the soldiers.

Children were said to have had wire hammered through their ears and jaws by the soldiers.

Another witness described how when Hamman Yaji learned of the deep significance of the burial rights in Sukur, he ordered his soldiers to cut up the bodies of the dead so they couldn't be given a proper burial.

Boko Haram has ravaged Sukur, a hilltop village I knew well. The village is deserted now, the people's ancient tribal culture destroyed.

Rabih's and Hamman Yaji's descendants (and there are hundreds of them) still live in the area. I wonder how many of them are active in Boko Haram today?

John Hare was a district officer for the British and Nigerian governments and worked for the United Nations Environment Programme. He then established the Wild Camel Protection Foundation to save the critically endangered wild double-humped camel in Central Asia from extinction. A Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, Hare has received numerous awards for his exploratory and conservation activities.