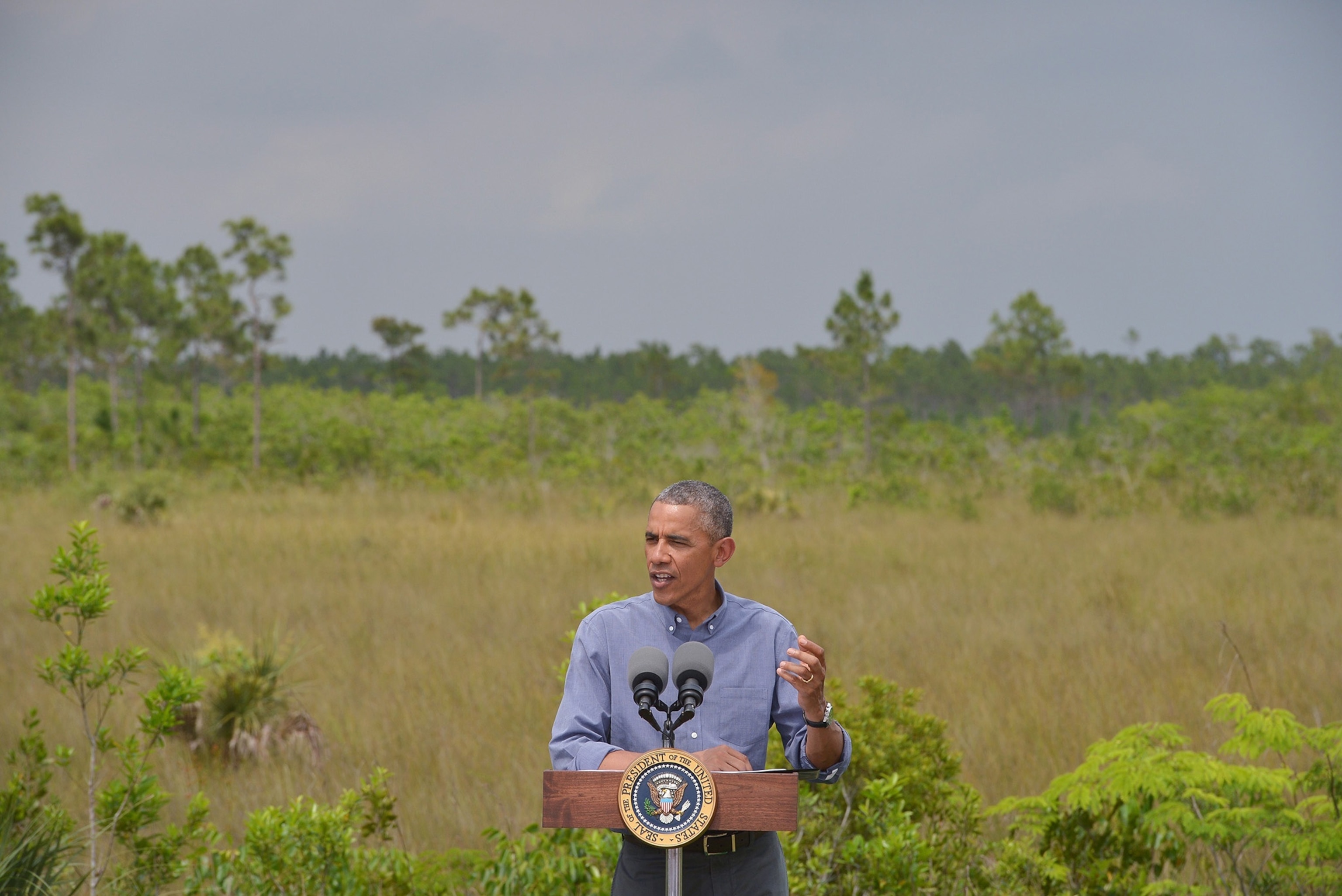

Why Obama Went to the Everglades for Earth Day

The president chooses the nation’s most vulnerable state to talk about impacts of climate change and rising sea levels.

As a prop for President Obama’s Earth Day speech on climate change, the Everglades lacked the dramatic imagery of shrinking glaciers in Alaska or the drought-stricken peaks of California. But Florida’s great swamp provided an urgency that other settings couldn’t:

South Florida already is in trouble from rising seas.

The third most populous state is one of the most vulnerable places on Earth to climate change. The combination of low, flat landscape and population density—three-fourths of its 19.9 million residents live in coastal counties—creates uniquely compelling climate challenges for the coming decades.

Already, more than half of Florida’s 825 miles of sandy beaches is eroding. Tourist destinations such as Miami Beach and Fort Lauderdale have endured sunny-day flooding during exceptionally high tides for years.

The Everglades protects the aquifers of South Florida, so as sea level rises, so does the prospect that the drinking water of seven million people will become too salty.

“We do not have time to deny the effects of climate change, folks,” Obama said Wednesday in a speech at Everglades National Park. “Nowhere is it going to have a bigger impact than here in South Florida.” (Read more about Obama's Earth Day announcements.)

Drinking Water at Risk

The president’s visit to the park was his first. He strolled with celebrity scientist Bill Nye along the Anhinga Trail, named for the long-necked water bird that swims underwater to hunt for fish. The boardwalk circles through a sawgrass marsh past the scene of a legendary 2003 battle between an adult alligator and a Burmese python that played out for 24 hours in front of horrified tourists, propelling the Everglades’ invasive python problem into the headlines.

“South Florida, you’re getting your drinking water from this area and it depends on this,” Obama said.

The only subtropical wilderness in North America, Everglades National Park is home to such endangered or threatened species as Florida panthers, American crocodiles, manatees, and a long list of birds. At 1.5 million acres, it is the largest wilderness east of the Rockies. Two-thirds of the park lies near sea level, at an elevation below three feet.

But the Everglades isn’t only a sanctuary for animals. The freshwater marshes of the River of Grass, as it also is known, refills and protects the Biscayne Aquifer, the vast underground basin beneath South Florida that supplies drinking water to one-third of the state’s population.

This occurs in two ways. Surface water in the marshes seeps through porous limestone bedrock into the aquifer. And, if there is enough fresh water flowing through the marshes, it pushes back salt water.

“The Everglades and the drinking water supply are very much connected,” says Jayantha Obeysekera, chief modeler for the South Florida Water Management District. “The more water you bring into the aquifer, the more it helps [stop] salt-water intrusion near the ocean. You have to have more fresh water to push the salt water out.”

The Everglades of today is about half its original size and is undergoing a restoration billed as the biggest environmental rehabilitation in U.S. history.

In mid-century, Florida’s original developers built hundreds of miles of canals to drain the swampland and create farmland and salable real estate.

President Obama’s Mixed Environmental Legacy in 8 Pictures

The canals, operating on gravity, move water out to the ocean. As seas rise along the Florida coast—now at a rate that is six times faster than at any time in the past 3,000 years—the canals can’t drain. Instead, they flood into the interior of South Florida. Pumps and gates installed on some canals prevent flooding now. A two-foot rise in sea level would render more than 80 percent of the gates inoperable.

Already, salt-water intrusion has forced some wells along the coast that supply suburban water systems to be relocated inland. The Army Corps of Engineers and the South Florida Water Management District are developing a new 50-year plan to “replumb” the canals.

Obama’s Message to Skeptics

The president’s choice of Florida for his Earth Day excursion also provided him with a political gift too irresistible to pass up—the chance to jab Republican leaders for failing to embrace the science of climate change. (Read "Earth's Dashboard Is Flashing Red—Are Enough People Listening?")

In what scientists call the most at-risk state, Governor Rick Scott and two presidential contenders, former Governor Jeb Bush and Senator Marco Rubio, remain skeptical that climate change will have dramatic effects. Bush hasn’t said much other than he is “concerned,” while Rubio questions whether climate change is caused by human activity. Scott cemented his image as a skeptic in his first term with his declaration “I’m not a scientist.”

Two months into Scott’s second term, the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting exposed a directive prohibiting some state officials from using the terms “climate change” and “global warming.” When Scott disputed the claim, several state officials stepped forward to say they had been pressured to remove those terms from their written work.

“So climate change can no longer be denied. It can’t be edited out. It can’t be omitted from the conversation,” Obama said.

The president also named a list of Republican presidents—including Theodore Roosevelt, who established the national park system, and Richard Nixon, who created the Environmental Protection Agency—who have promoted environmental protections.

“This is not something that historically should be a partisan issue,” he said.

Not Just Theory to City Planners

In the meantime, many local officials in Florida say they’ve no time to debate whether climate change is real.

This is not something that historically should be a partisan issue.President Obama

In Miami Beach, with millions of dollars’ worth of real estate at risk, leaders call their barrier island “ground zero of ground zero.” They, along with leaders in the four southeastern counties—Miami-Dade, Broward, Palm Beach, and Monroe—are drafting plans to reengineer their network of suburbs through 2060, when sea level is expected to rise two feet. That includes raising seawalls, roads, and highways; rezoning land that can’t be protected; and abandoning lowland that floods today.

Miami Beach is spending more than $400 million, most of it on new pumps, to overhaul a storm drainage system and stop street flooding that occurs regularly. The pumps are designed to buy time.

This spring, Miami Beach has launched a second front against advancing seas: elevating sidewalks and roads.

While Obama toured the sawgrass, construction crews in Miami Beach spread out along a three-block stretch of 17th Street, where they are raising the sidewalks by 18 inches. It is another measure to buy time.

“We have no alternative,” says Bruce Mowry, the city’s engineer. “We have to adapt. We can’t ignore it.”

Follow Laura Parker on Twitter.