What we know now about how ancient archers made their bows

In Spain, the Cave of the Bats, Albuñol, held a major secret: bowstrings discovered in the 19th century predate those used by the ice mummy Ötzi by more than two millennia, shedding new light on Neolithic archery.

Fresh analysis of a collection of sinew bowstrings and arrow fragments is rewriting the history of Neolithic archery. The artifacts recovered in the shelter of the Cave of the Bats, Albuñol, in Spain, were originally discovered by miners in the 19th century. These finds were recently analyzed by a team of archaeologists using an unprecedented combination of microscopy and biomolecular methods.

Preserved for more than seven millennia, the bowstrings were revealed to pre-date the weaponry of Ötzi, the ice mummy discovered in the Ötztal Alps, by more than 2,000 years—pushing back the timeline for animal-derived bowstrings in present-day Europe. The groundbreaking study, published in Scientific Reports in 2024, offers startling new insights into the technical mastery of Neolithic archery in the Iberian Peninsula.

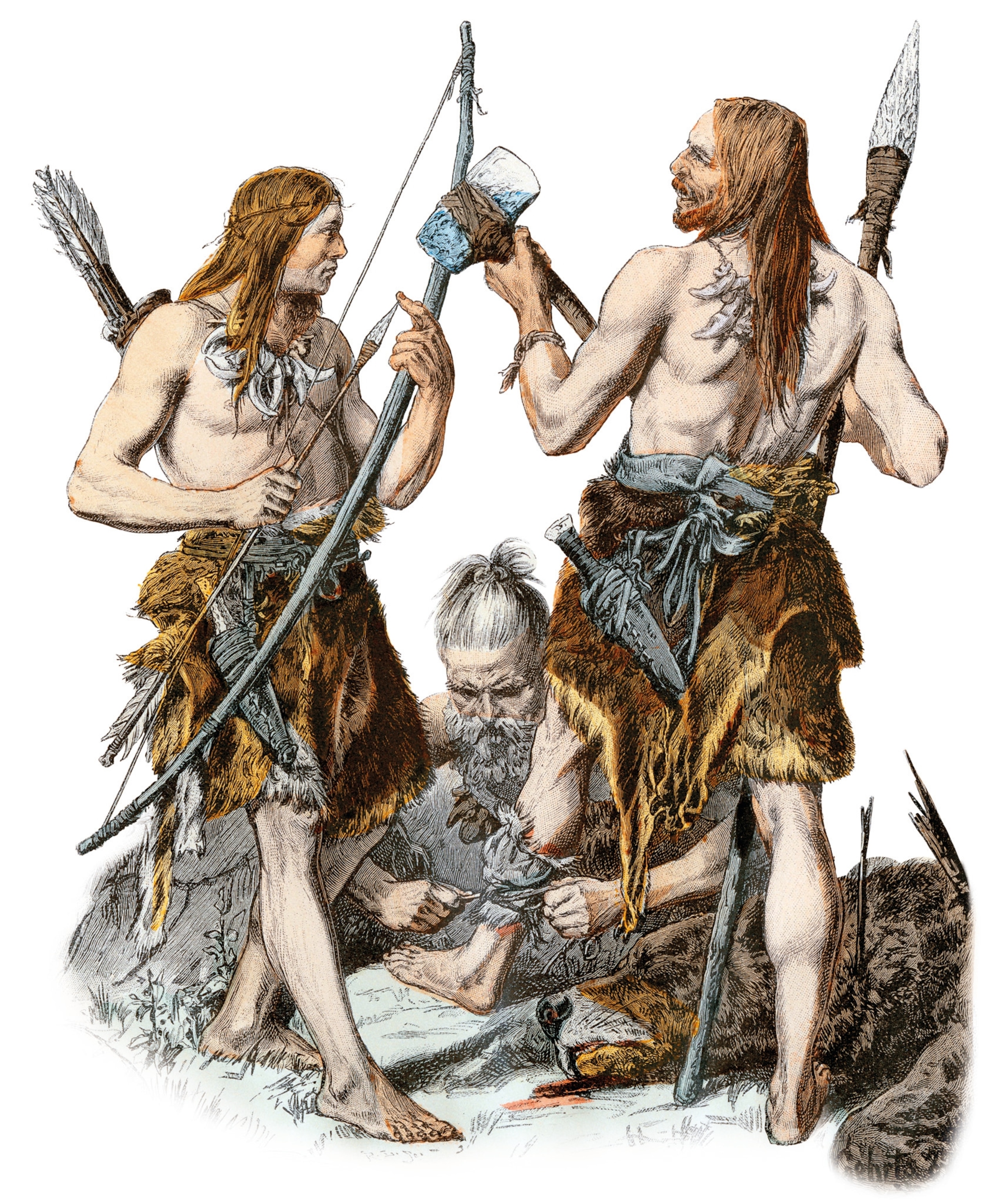

Mastering the bow

The Cave of the Bats, Albuñol, (Cueva de los Murciélagos de Albuñol) lies in the Sierra de la Contraviesa near the city of Granada. Perched at the edge of a steep ravine, the cave was used to shelter livestock in the early 19th century, before miners found it contained lead-rich rock in 1857. As they removed stone to extract the ore, they broke into a hidden tunnel, uncovering skeletal remains and artifacts related to archery. The finds were later recovered by an archaeologist in the 1860s and housed in Madrid’s and Granada’s archaeological museums. More recently, excavations in the cave, led by archaeologist Francisco Martínez-Sevilla of the University of Alcalá, revealed a bowstring, which led to a more in-depth study of the miners’ archery finds. The results were groundbreaking. Ingrid Bertin of the Autonomous University of Barcelona, first author for the study’s paper, told History: “What is incredible about the cave is how its exceptionally dry conditions preserve everything so well.”

Oldest bowstrings

Radiocarbon dating of the prior discoveries revealed that two bowstrings and arrow fragments dated as far back as the late sixth to early fifth millennium B.C., during the Neolithic period. Molecular analysis was used to identify what the items were made of, and for the first time, researchers were able to identify the animals used for the bowstrings: roe deer, as well as unidentified species from the pig and goat families. Tendons were twisted together to form strong, flexible cords that would, according to the paper, “meet the needs of experienced archers.”

(What was the Neolithic Revolution?)

Previously, the only early Neolithic bowstring found in Europe was a cord from a site called La Draga in Catalonia, Spain—made of nettle, not animal sinew. At the time, it offered new insights into early archery methods but left major gaps in how bowstrings were made and what materials were favored. The new analysis has also revealed that the arrow shafts were made of olive wood and reed, confirming the longtime speculation by archaeologists that reeds were used to make arrows in prehistoric Europe.

According to Bertin, the combination of olive wood and reeds would have “significantly improved the ballistic properties of the arrows, with a hard and dense front section complemented by a light back, and tips made of wood without stone or bone projectiles.”

Even older than Ötzi's bow

(Ötzi the Iceman: What we know 3 decades after his discovery)

Beyond the hunt

The artifacts and archery equipment are part of a set of grave goods found in the cave, which also include remains of clothing, mats, wooden and fiber-based containers, fragments of rope, and a torch. For the archaeological team, this points to the archery items having a special meaning for the cave’s early Neolithic dwellers. Hunting at the time was no longer a primary means of subsistence, as agriculture was taking hold. It evolved into a symbolic and social activity, closely tied to social and political status.

Future experiments will involve duplicating the arrows to clarify if they were used for hunting or close-range combat, or if they could, in fact, have been nonlethal arrows, helping to confirm the idea that archery was full of symbolism for early Neolithic dwellers.

(Scientists reconstruct the tattoos of a 2,000-year-old Siberian ice mummy)

Treasures of a bat cave