Watch: How to Become a Space Archaeologist

New online tool enables anyone with Internet access to search satellite images for ancient ruins.

She’s been described as a hybrid of Indiana Jones and Google Earth. Now archaeologist Sarah Parcak—who pioneered the use of satellite imagery to discover lost cities and buried ruins—has an ambitious plan to use technology and crowdsourcing to protect remnants of the ancient world.

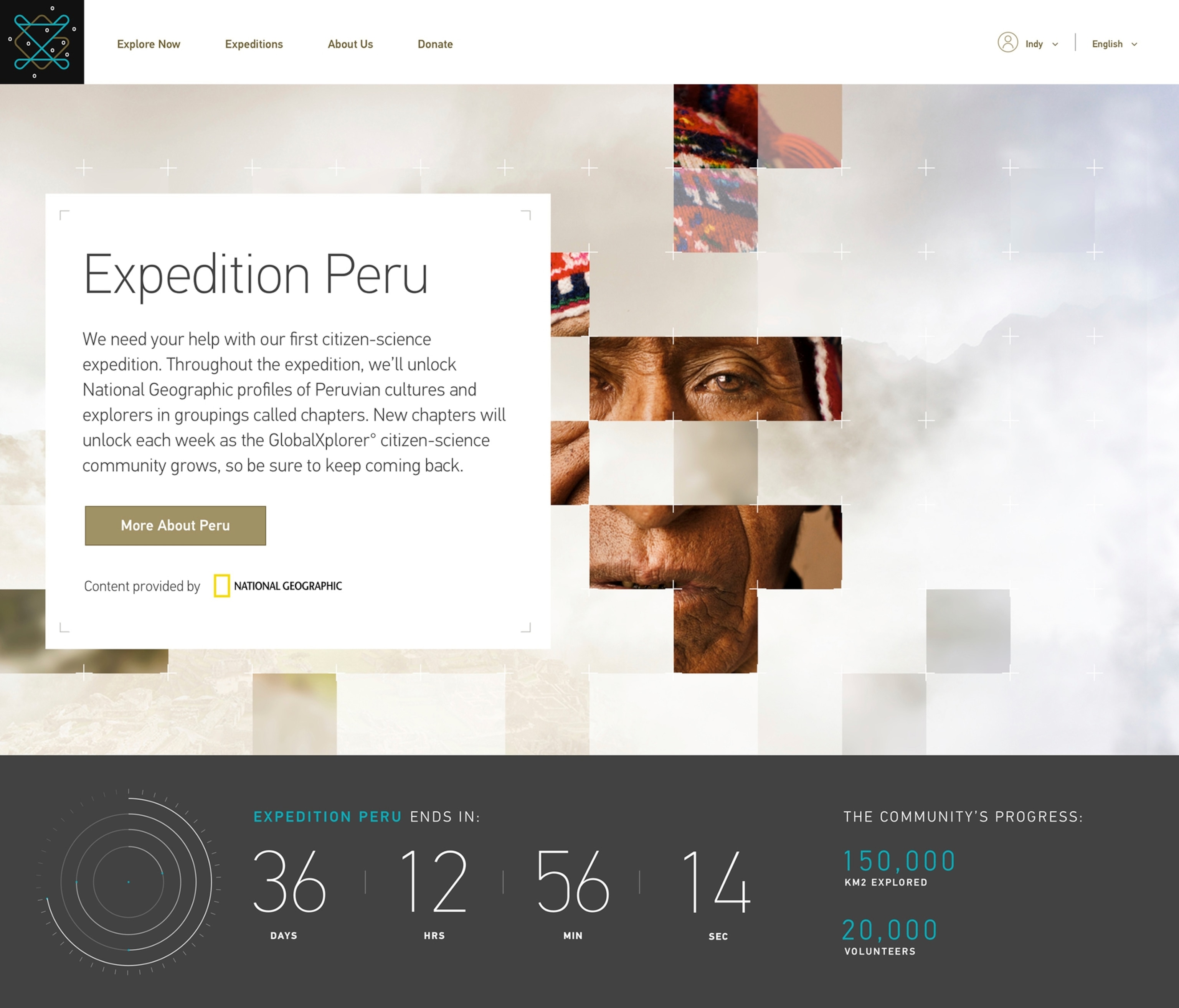

Today Parcak launches GlobalXplorer°, an online tool that’s part of a coordinated global effort to use technology to spur discovery and outpace destruction.

“Archaeologists can’t do this on their own,” says Parcak, who estimates that only one percent of the world’s archaeological sites have been identified, let alone explored and studied. “If we don't go and find these sites, looters will.”

Archaeologists can't do this on their own. If we don't go and find these sites, looters will.Sarah Parcak, Archaeologist

Parcak, a National Geographic Fellow and founding director of the Laboratory for Global Observation at the University of Alabama, is enlisting an army of amateur archaeologists to study satellite images for signs of looting and destruction and spur the discovery of archaeological sites. Parcak won the 2016 TED Prize, awarded each year to an innovator with an audacious and creative vision for global change. Winners use the $1 million prize money to invest in a project of their choice.

“Most people don’t get to make scientific contributions or discoveries in their everyday lives,” Parcak says. “But we’re all born explorers, curious and intrinsically interested in other humans. We want to find out more about other people, and about ourselves and our past.”

See Peru—from Space

The inaugural online expedition of GlobalXplorer° will take participants to Peru via high-resolution satellite images shot from 435 miles above the Earth. After a short tutorial (in English or Spanish), budding archaeologists can search through “tiles,” or snapshots of the Earth’s surface, looking for hints of looting, construction, or other encroachment, as well as signs of ruins that modern archaeologists have yet to find. Advanced users will have access to images that reveal differences in vegetation health—a clue to what lies hidden in the soil, such as buried ruins.

Preventing looters from finding new sites was central to building the GlobalXplorer° platform. The high-resolution satellite images are broken into tens of millions of small tiles and displayed to users in a random order without the ability to navigate or pan out. The tiles do not contain any location reference or coordinate information.

Most of the images will reveal nothing out of the ordinary, says Parcak, but even that’s useful, since it allows archaeologists to rule out those areas and focus on the ones that need attention.

If you’re used to playing fast-action video games, the pace of GlobalXplorer° won’t rev up your heart rate. But it offers another type of thrill.

“This is real science that will make a real difference,” says Parcak. “It will appeal to people who want to be part of the work that goes into making actual discoveries and solving ancient riddles—and stopping the destruction of our human heritage.”

Participants who make their way up the skills ladder will unlock “Expedition Rewards” from National Geographic, including subscriptions, team hangouts, video features, and articles from the magazine’s archives that offer insights into Peruvian history, culture, and explorers.

Parcak has partnered with acclaimed Peruvian archaeologist and National Geographic Explorer Luís Jaime Castillo of the Sustainable Preservation Initiative (SPI) to coordinate on-the-ground activities in Peru. As crowd-sourced data comes in, teams will be dispatched to investigate select sites and take action as needed, after consulting with Peru’s Ministry of Culture.

SPI will also help local residents who live near significant archaeological sites develop business and artisan skills so they can benefit from tourism.

“The trade in stolen antiquities is often driven by economic desperation, so we need to provide an incentive to local people to protect nearby riches,” says SPI executive director Lawrence Coben. “Archaeology can make a tremendous contribution to poorer communities if we can help them build livelihoods as well as save sites.”

"Grand Experiment"

Parcak cautions that the project is still a “grand experiment,” but remote imaging has already led to big discoveries. In Egypt, Parcak and her colleagues used satellite imagery to find a long-buried city that was touted in ancient hieroglyphs. This past June a consortium of archaeologists in Cambodia used airborne lasers to discover the jungle-covered remains of what was possibly the biggest pre-industrial city on Earth. A recent series of photos taken by DigitalGlobe—which is providing satellite images of Peru for the GlobalXplorer° project—showed a massive fortress thousands of years old on the Kazakhstan steppe.

But Parcak’s vision is bigger than any single discovery that her community of armchair archaeologists might make. Just as Hiram Bingham’s photos of Machu Picchu sparked a movement to discover and preserve archaeological sites at the turn of the 20th century, Parcak hopes GlobalXplorer will help catalyze a modern age of discovery and preservation—one that could give hope and perspective in these challenging times.

“Right now we could all use a healthy dose of understanding that we’re all the same species,” Parcak says. “Humanity has been down many difficult paths, and we’ve handled them with great resilience and creativity. When we look back through the millennia, we can see that our hopes and dreams and challenges really haven’t changed much.”

Click here to learn more about becoming a GlobalXplorer°.