My night with the guerrilla balloonists of South Korea

Inside a covert operation to bombard North Korea with pantyhose and nature films.

Do you know how to run fast?” asked a man I’ll call Park.

He was driving us carefully through dusk, well below the speed limit, from Seoul toward the infamous Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), the heavily mined frontier between South and North Korea. It was a warm summer evening. Park, a North Korean defector who allowed me to tag along provided he could use an assumed name, was keeping a wary eye on his rearview mirror for a police tail. The only vehicle shadowing us, thankfully, was a nondescript pickup truck steered by one of Park’s helpers. It was lugging, under a blue tarp, enough steel canisters of hydrogen to blow up a large house.

Park’s two-vehicle convoy wasn’t bound for some mission of terror. Instead, trundling past 7-Eleven convenience stores, rural churches topped with red neon crosses, and pig farms, he and his band of four activists were on a bizarre mission of political resistance, one that few if any outside journalists had witnessed before: the clandestine lofting of huge handmade balloons into the night skies above North Korea.

Over the past 12 years, I’ve hiked thousands of miles across the world for a National Geographic storytelling project called the Out of Eden Walk. Typically, I spend my days peering down at my plodding feet. Tonight, my attention would be focused up, on a group of improvised airships floating north on favorable summer winds, carrying a payload of items that are either subversive or in short supply in the most shuttered society on Earth.

The South Korean police might pull us over, Park warned. If that happened, he advised with a wink, I should bolt into the scrub. “I’ve been fined before, but I don’t care,” he said. “People in the North don’t even know what human rights are. Our balloons help wake them up.”

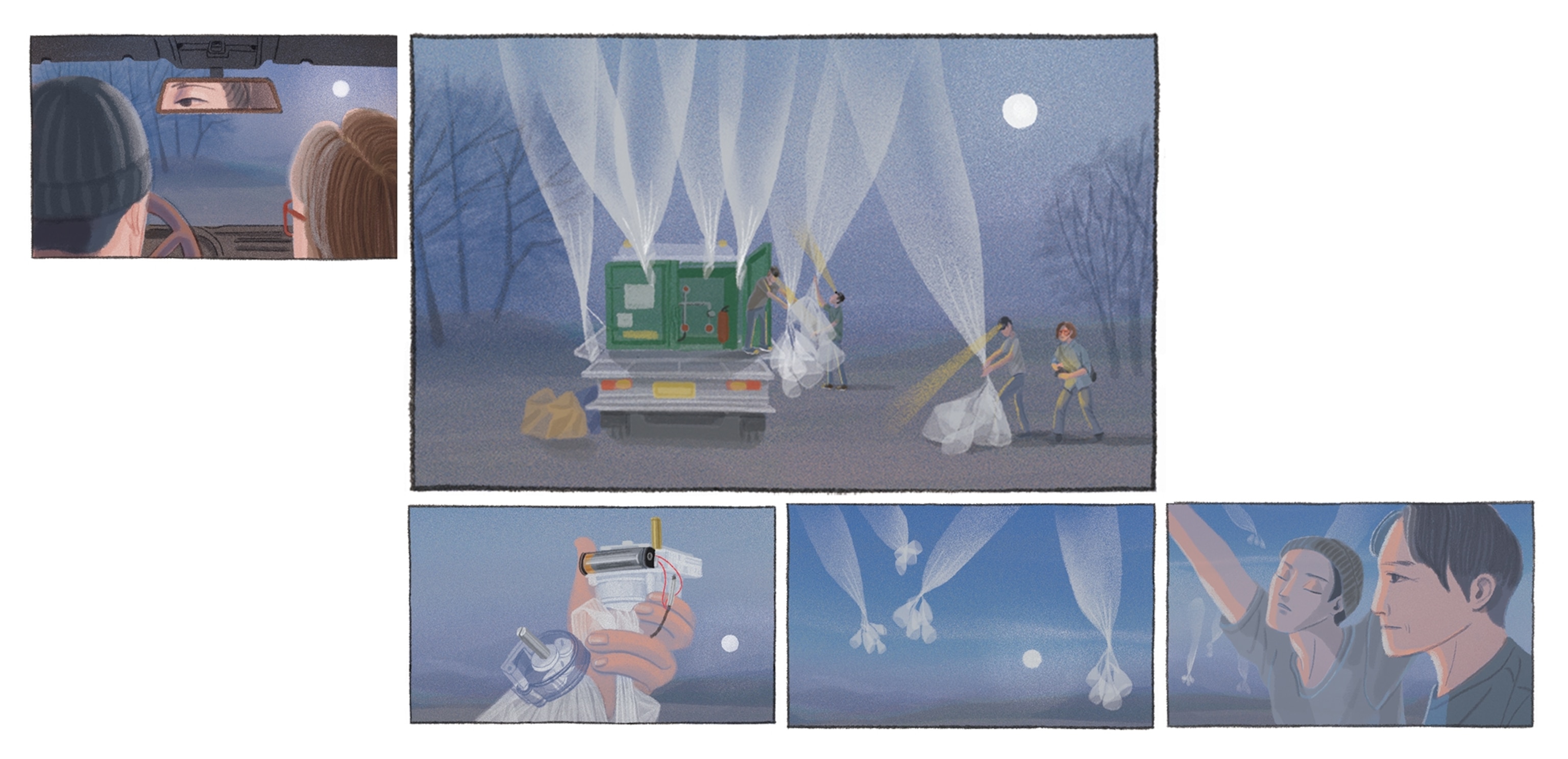

Hours later, parked in a weedy field near the DMZ, I watched as the guerrilla aeronauts bustled about the dark in headlamps, cranking open the hydrogen cylinders to inflate their balloons. Gas jetted from the tank valves with a startlingly loud hiss. The airships—loaded with items like biblical tracts, U.S. dollar bills, pro-democracy leaflets, rice, and women’s hygiene products—did not resemble the colorful vessels at hot-air balloon festivals. Rather, they were elongated, clear plastic mammoths, enlarging to heights of four or five stories tall.

(This is what daily life in North Korea looks like.)

Soon, 25 balloons jutted into the moonlit sky like monumental exclamation points that were surely visible for a mile.

Perhaps you’ll remember the media reports from South Korea last summer: Thousands of large balloons hauling plastic sacks bulging with cigarette butts, rotting clothes, worms, and even feces floated from North Korea into the airspace of democratic South Korea. This barrage of garbage triggered health alerts, fires, and aborted flights at airports. One bag of gunk landed near the South Korean president’s office in Seoul.

The press often covered this armada of inflatables with a smirk, as a sideshow to an ongoing rivalry between sister nations that remain bitter enemies 72 years after Korea’s civil war was paused by a ceasefire. Yet the public rarely heard the other half of the story: The North Korean rubbish attacks were payback for South Korean propaganda balloons like Park’s.

(Finding the ordinary amid North Korea’s extravagant propaganda displays.)

The geopolitics of this tit-for-tat aerial dispute, however, wasn’t nearly as illuminating to me as the earnest motivations of the South Korean activists, many of whom are in fact North Korean defectors. The teams of balloonists appear driven by a marooned sort of longing for all they’ve left irrevocably behind: abandoned loved ones, landscapes of memory, youth. (When it comes to the finality of exile, North Koreans rank in a bleak class of their own; among some 34,000 defectors in South Korea, barely a few dozen are known to have voluntarily returned to the brutal clutches of their police state.)

In this way, the strange balloon war resembles texts exchanged between a couple in a toxic relationship, with one partner appealing for connection while the other replies with trash talk. The exchanges carry added poignancy since reunification of the two countries seems more implausible than ever. Today fewer and fewer young South Koreans support it, while North Korea has pivoted decisively away.

“My family is very lucky, very grateful to be free,” said Park, 28, who grew up in North Korea listening to Western radio broadcasts muffled under a blanket in his bed, a thought crime punishable by prison. “We’re not just living life for ourselves now, but for the people back in North Korea.”

Energetic and wiry, Park recounted in confidence his perilous escape from North Korea with four relatives more than a decade ago. Now a youth organizer for an Evangelical church outside of Seoul, he explained how fellow Christians in North Korea risked execution for practicing their faith under the cultlike rule of supreme leader Kim Jong Un. He also bemoaned the sinister reach of North Korea’s intelligence agencies, which had poisoned the dictator’s own brother in exile in Malaysia. Arriving as a teenager in go-go South Korea from repressive North Korea, Park recalled, had felt like being a person from the 1970s transported to modern-day New York.

“North Koreans find it very hard here,” sighed Kim Seung-Chul, reflecting on the balloonists’ experience. “Some [South Koreans] see North Koreans as less intelligent, primitive.” An older-generation defector, Kim arrived in South Korea in 1993 after walking away from a work camp in Siberia. He now operates a pro-democracy radio station in Seoul. Even after three decades in the country, Kim noted dryly, he sometimes feels like an outsider. His South Korean wife has been reproached by her friends: Why are you still living with the North Korean?

Though sailing private balloons into the North was criminalized in 2020, the prohibition was struck down by South Korea’s Constitutional Court two years ago on free speech grounds. Still, the night launches remain a fraught calling. Seoul doesn’t appreciate the diplomatic aggravation. The police issue hefty safety fines. Lee Min-Bok, a craggy defector in his sixties, had his balloon truck torched. “Could be a North Korean spy,” said Lee, a former agricultural engineer in the North. “Or a pro-North Korean citizen here.” He added, “There are people who disapprove.” He means Communist sympathizers.

Lee launches his airships at night from a remote valley near the DMZ. He packs the balloons with thousands of pages of photocopied essays on free will, and, less frequently, with aspirin, thumb drives loaded with nature documentaries, women’s nylons—anything scarce in the threadbare North. He lives in a rusting shipping container at the site. His South Korean wife and son deserted him for California. Desperate to connect with someone on the other side of the fortified border, he takes the risk of including his real name and phone number on his political leaflets. After years of balloon releases, he admitted wearily, nobody has called.

My entrée to the ballooning world, the younger Park, still possesses a novice’s enthusiasm. His balloons are constructed from tough but lightweight plastic normally used for agricultural purposes. An electronic altimeter triggers clamps to release sacks of religious literature, cash, and other cargo from about 5,000 feet. The bags float down on tiny parachutes, which Park tracks via GPS devices.

On the night that he allowed me to join him, his crew released all of their balloons at once. Park, arms stretched skyward, muttered a prayer. The team stood gazing up for long seconds as the 25 balloons fluttered and climbed in the night breeze. Park said the balloons would be picked up by South Korean radar in 29 minutes, after which military police would come to investigate. The balloonists began loading up in haste to depart. I watched their handiwork ghost up into the darkness like a sad miracle.

(Take a train through North Korea's rarely seen countryside.)

Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Paul Salopek has been a National Geographic Explorer since 2012. For the past 12 years, he has covered some 16,000 miles in his ongoing walk retracing human migration out of Africa. The nonprofit National Geographic Society has funded Salopek's Out of Eden Walk. Follow him at OutofEdenWalk.org.

An artist living in Seoul, South Korea, Jiyeun Kang is a winner of multiple American Illustration awards and has done work for publications including Allure, Backpacker, the Boston Globe, and Politico. These are her first illustrations for National Geographic.