The mystery woman at the heart of Beethoven’s secret love affair

The discovery of a love letter revealed the depths of Beethoven’s yearning for his "immortal beloved." Scholars have been piecing together clues to her identity ever since.

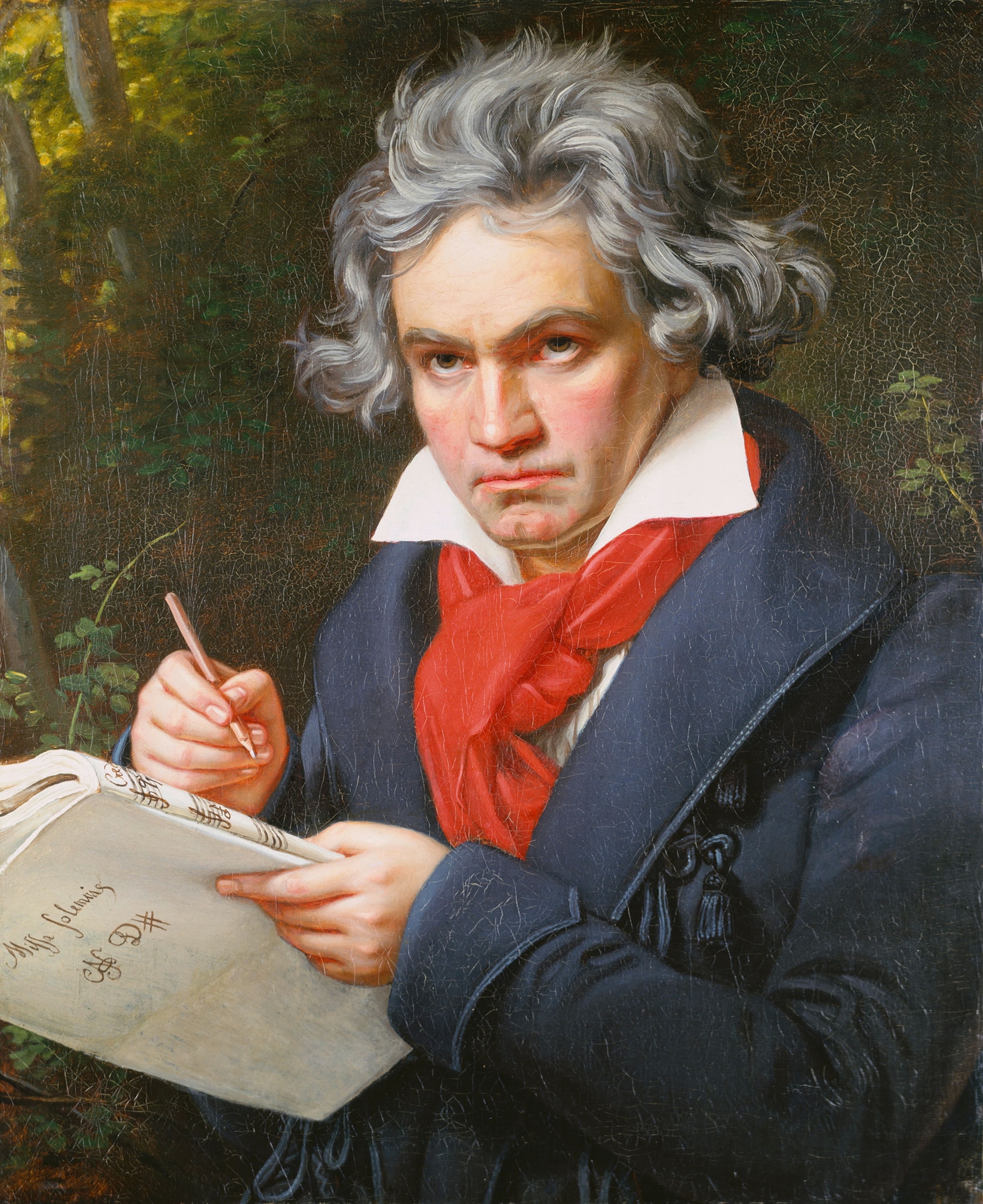

Ludwig van Beethoven appeared to be as unsuccessful in love as he was successful in music.

When the celebrated composer died on March 26, 1827, he left no widow to mourn him—just an adoring public who lined the streets to catch a glimpse of his funeral procession.

But when Beethoven’s secretary Anton Schindler went through his late employer’s desk, he made a discovery that kickstarted one of music history’s most romantic mysteries.

Inside the desk was a yearning, passionate, and lyrical love letter that Beethoven seemed to have never sent. Beethoven did not name his intended recipient. Instead, he referred to her as his “Immortal Beloved.” “I can live only wholly with you or not at all,” he wrote, “yes, I am resolved to wander so long away from you until I can fly to your arms and say that I am really at home, send my soul enwrapped in you into the land of spirits.”

(What happens to your body when you’re in love—and when you’re heartbroken.)

It clearly wasn’t a love letter penned to someone he admired from afar. “The entire text of Beethoven’s letter suggests that his love was reciprocated,” says Julia Ronge, curator of the collections at Beethoven-Haus Bonn. Despite this, their romance ultimately ended since Beethoven never married.

Who was Beethoven’s “Immortal Beloved”? That phrase has since captured the imagination of scholars, filmmakers, writers, and fans alike, who have pieced together clues from the letter and Beethoven’s life to put forward potential candidates.

Sifting through the clues

There isn’t a single obvious candidate for the object of Beethoven’s desire. He’s known to have fallen in and out of love with women who would not marry him, explains musicologist John David Wilson, senior research fellow at the University of Vienna. He “was earning a lot better than a lot of musicians, but it was quite an unstable life, which made him de facto ineligible for marriage for a lot of the kind of women that he was in love with.”

One of those women was likely the intended recipient of the letter.

“I have counted 13 candidates who were brought into play at some point by someone in the past 200 years,” Ronge says.

What makes a potential candidate?

First, the timing. Though Beethoven does not provide a specific year, he wrote the letter in multiple parts and timestamped them on Monday, July 6 and Tuesday, July 7. An analysis of a watermark on the letter’s paper confirmed that it had likely been written in 1812, one of the few years when July 6 and 7 fell on a Monday and Tuesday during his career. The immortal beloved had to have been in Beethoven’s life at that time.

The dating of the letter to July 1812 precludes some early candidates, such as Giulietta Guicciardi, Beethoven’s one-time pupil and a noblewoman he had courted in the early 1800s and to whom he had dedicated “Moonlight Sonata.”

(How Beethoven "undedicated" his Third Symphony to Napoleon.)

Second, the location. Based on the timing, scholars know Beethoven had traveled from Prague to Teplitz, a spa town in what is today the Czech Republic, just before writing the letter.

According to Jan Caeyers, conductor, musicologist, and author of Beethoven, A Life, Beethoven and the intended recipient seem to have had an “intense night together in Prague” based on the tone of the letter. They then parted ways, Beethoven to Teplitz and the woman to Karlsbad, known today as Karlovy Vary in the Czech Republic. So, the woman must have been in both Prague and Karlsbad in July 1812.

Third, there had to be some kind of barrier to their relationship. Beethoven lamented that it wasn’t possible for the pair to live together, wondering, “Can you change it that you are not wholly mine, I not wholly thine?” Most scholars believe this means the immortal beloved was a married woman.

With these criteria in mind, scholars have identified two candidates who stand out above the rest.

Candidate 1: Antonie Brentano, one of Beethoven’s patrons

Born in 1780 and married to wealthy merchant Franz Brentano, Antonie first met Beethoven in 1810. She and her husband became his friends and patrons, giving him money and support.

Brentano’s feelings for Beethoven ran deep. In a 1811 letter to a relation, she claimed to “venerate deeply” the composer and believed he “walks god-like among the mortals.”

But was she the immortal beloved? Sylvia Bowden, lecturer at the University of Southampton, notes Beethoven “clearly had a close bond with Antonie and her family, which included her husband and children.”

“All the available evidence points to Antonie as the intended recipient of the letter,” she argues. Brentano was in Prague before heading to Karlsbad in July 1812. Furthermore, Brentano’s status as a married woman, and the wife of Beethoven’s friend no less, provided an obvious barrier to a romance.

(Do you have a morning routine? Here was Beethoven's.)

The late scholar Maynard Solomon was a leading proponent of the Brentano theory and claimed Beethoven’s “love for Antonie [was] in conflict not only with his deeply rooted inability to marry but also with the prospect of the betrayal of a friend.”

Others are less convinced. Wilson points out there isn’t “any evidence that she and Beethoven were ever more than friends.” And, they argue, there’s another convincing candidate.

Candidate 2: Josephine Brunsvik, Beethoven’s piano student

“The evidence strongly points to one person: Josephine Brunsvik,” says Ronge.

Beethoven first met 20-year-old Brunsvik in 1799 when he was hired to give her piano lessons, but their relationship blossomed years later when she became a young widow. The pair exchanged 14 love letters between 1805 and 1807. Beethoven used the same terms of endearment as in the immortal beloved letter, including “angel” and “beloved.”

The relationship also shaped his music. “There were a few pieces he specifically wrote for Josephine,” Caeyers says, including some “pieces where you can hear hidden messages from Beethoven to her.” One of the pieces written with Josephine in mind is Andante favori, whose opening theme seems to reflect the syllables of her name.

Ronge explains that the late musicologist Rita Steblin unearthed documents, including letters and diaries, that “suggest she was Beethoven’s immortal beloved.”

“[Brunsvik] fulfills many of the conditions mentioned in the letter: she is married (i.e. not free), she is noble (i.e. of a different class than Beethoven), and she was in Prague on the night in question to which Beethoven refers,” Ronge says.

Caeyers agrees that Steblin’s “arguments are persuading.”

But there’s no concrete evidence that Beethoven and Brunsvik stayed in touch after their correspondence ended in 1807. Moreover, Bowden points out “there is no evidence to show that she was in Karlsbad in the summer of 1812."

But the timing makes Brunsvik’s candidacy theoretically plausible. Her second marriage, which began in 1810, was on the rocks by the time Beethoven wrote the letter. Had she rekindled a relationship with her former suitor at this time—and was this letter the only evidence that survived?

Wilson concedes it’s possible that the pair had reconnected but that their relationship was “suppressed.” Caeyers suggests that Brunsvik’s aristocratic family may have gone out of its way to hide the relationship as any hint of a scandal would have been “bad for the reputation of the family.”

And some scholars argue there may have been reason for her family to worry.

The key to solving the mystery?

There’s one more tantalizing clue in Brunsvik’s candidacy: Though she was estranged from her husband in July 1812, she gave birth to a child nine months later.

Minona von Stackelberg was born on April 9, 1813, and was officially the child of Josephine’s second husband Christoph von Stackelberg.

Yet some wonder if she was Beethoven’s daughter. Steblin theorized that Minona’s “name is symbolic,” since it’s the name of “the daughter of a musician in the highly-influential tales of the (fictional) Scottish bard Ossian,” one of Beethoven’s favorite poets.

Minona died in 1897 and was buried in a known grave at Vienna Central Cemetery.

Caeyers suggests genetically testing von Stackelberg’s remains against Beethoven’s DNA—which was analyzed in 2023 from surviving locks of his hair—could be one way to find answers. “If Minona is Beethoven’s daughter, then it’s clear Josephine was the immortal beloved.”

The same logic applies for Karl Josef Brentano, the child that Antonie bore on March 8, 1813, eight months after the letter was written. His burial site is also known: the Brentano family crypt in Frankfurt.

However, Caeyers concedes accessing any remains for testing is easier said than done. Due to strict rules governing exhumation, we may never definitively prove the immortal beloved’s identity. Still, one truth remains: after two centuries, the letter still grips our imagination.

“This is all part of a picture of a great artist who suffered a tremendous romantic setback,” says Wilson. “We know by the time the letter was written, he had largely given up the hope of having a family or at least marrying, and this made him double down and really devote even more energy into his work.”

The letter also “changes the image of Beethoven,” says Caeyers. “The whole story makes him more human and vulnerable.” He wasn’t just a lonely musical genius who “transcends the banalities of life.” Beethoven experienced great love—and great heartbreak—just like the rest of us.