The slow-burning crisis that sparked the Capitol violence was right before our eyes

For months, photographer Louie Palu has chronicled Washington as the capital weathered a deadly pandemic, protests against racial injustice, unfounded claims of election fraud and an insurrection.

At this moment, our constitutional system is imperiled. When and how this crisis ends is anything but clear.

As I write this, law enforcement officials and the U.S. military leaders are braced for a reprise of violent uprising in the nation’s capital. Extremists and armed militia—inflamed by President Donald Trump’s disproven claims of election fraud and his encouragement to “fight like hell”—are threatening to attack state capitol buildings and disrupt the inauguration of Joe Biden on January 20. Right-wing chat groups teem with vows to kill Democrats (labeled by Trump as “human scum”) and members of the media (described by the president as “enemies of the American people”). We are living in history, and not in a good way.

The storming of the U.S. Capitol on January 6 shocked the nation. Now, in anticipation of more violence surrounding the upcoming inauguration, the grounds near the Capitol have been fenced and militarized, while nearby businesses have been boarded up. The president has been impeached an unprecedented second time. Across the country, an FBI dragnet is hunting the perpetrators who invaded the Capitol. On Inauguration Day, the National Mall, usually jammed with thousands celebrating the quadrennial spectacle, will be closed to the public. America is now divided like no time since seven of its states seceded from the union, thereby ushering in a bloody four-year civil war.

That is where we are. But when did this political roller-coaster ride careen into its frightful descent?

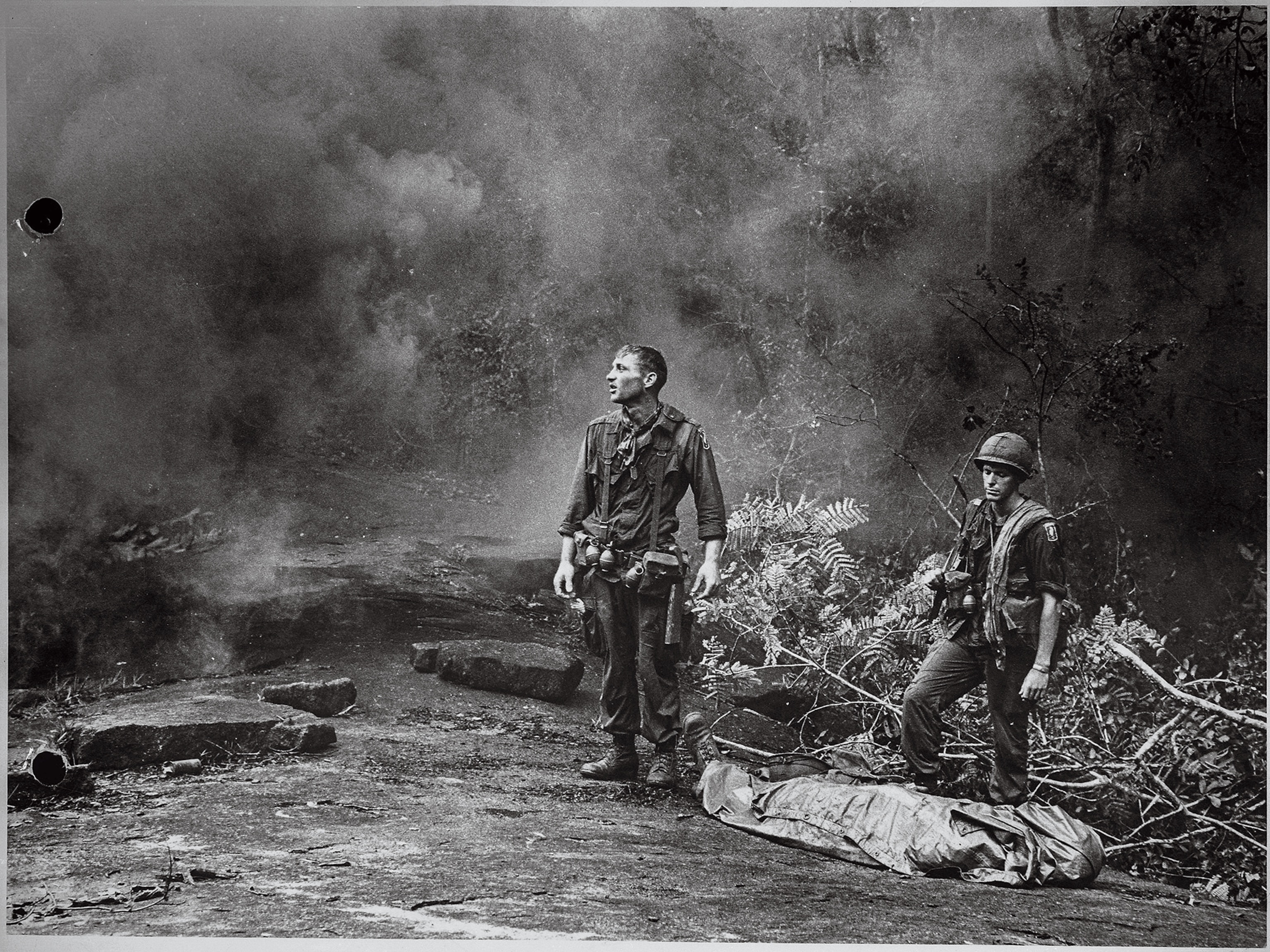

Photographer Louie Palu has attempted to address this question. The native Canadian and Guggenheim fellow has spent much of the past decade documenting the travails of violence-stricken countries like Afghanistan and the drug-trafficking corridors of Mexico. Unexpectedly, the same theme would lure him to America’s capital city. This past May, Palu began photographing every demonstration in Washington, not sure where all this would take him. (Since September, his work has been supported by a grant from the National Geographic Society.)

Palu was in Lafayette Square on June 1 when U.S. Park Police and National Guard troops deployed tear gas to disperse protesters so that Trump could stride out of the White House, cross Pennsylvania Avenue, and pose for a photo op standing in front of St. John’s Church, where he wordlessly held aloft a Bible.

As his images remind us, the protests last summer were about racial injustice in the wake of the death of a Black man named George Floyd who was crushed by a white policeman. Trump responded by depicting the at-times destructive behavior as the foul work of Antifa anarchists. He mocked the Democratic mayors of targeted cities for being too indulgent of the protesters, telling them they needed to “get much tougher” and to “dominate.” He then showed them what he meant in Lafayette Square. At the same time, in describing the Black Lives Matter movement as a “symbol of hate,” Trump normalized the open expression of the racial resentments that seethed through much of his base.

Arguably Trump may have won a second term but for his administration’s mismanagement of the pandemic. Palu’s photos capture administration officials trying to deal with the spiraling crisis at the same time the president was downplaying it. To many Americans, as the virus’s death toll by Election Day surged well past two hundred thousand, the president’s “it will all go away, like a miracle” bravado had taken on lethal proportions. An image of Trump’s announcing his nomination of Amy Coney Barrett for U.S. Supreme Court justice in the White House Rose Garden is a panorama of maskless attendees. Many later would test positive for COVID-19—as would the president himself.

Even before the election results began to trickle in on November 3, Trump was insistent that the Democrats would rig the outcome. The refrain was familiar. After losing his very first electoral contest, the Iowa caucuses, in 2016, Trump baselessly claimed that Ted Cruz had won because of fraud. Later that November, after beating Hillary Clinton but losing the popular vote, he offered the unfounded explanation that millions had voted illegally. Now here he was again, repeatedly insisting the election was stolen—a refrain quickly taken up by many other Republicans.

Palu captured Trump’s personal lawyer, Rudy Giuliani, leaving the Republican National Committee offices two weeks after the election. Without evidence, Giuliani alleged a conspiracy to commit fraud in big cities controlled by Democrats, declaring. “I know crimes. I can smell them.” The president’s lawyers pursued baseless lawsuits around the country, which even Trump-appointed judges rejected. On December 1, William Barr, then U.S. attorney general, announced that Trump’s Justice Department had found no widespread voting irregularities. Palu caught Barr in the Capitol, wearing a mask and sanitizing his hands, on the day he authorized that investigation. That Trump and his loyal allies turned up absolutely no proof to buttress his claims does not seem to matter to his supporters, some of whom subsequently breached the Capitol. After all, his fact-free assertions square with greater truths embraced by much of the U.S. electorate—namely, that the nation’s leaders are corrupt, incompetent, and indifferent to the growing malaise of “the forgotten Americans,” as Trump termed them.

Palu’s pursuit took a more ominous turn after the election. On December 12, the photographer attended a gathering of the far-right, neo-fascist group known as the Proud Boys in front of the Washington Monument. Ten weeks earlier during the first presidential debate with Biden, the president had refused to condemn the violent acts committed by white supremacists— instead telling the Proud Boys, “Stand back and stand by.” Now here they were in Washington, 400 strong. Many of them wore the group’s trademark black-and-yellow regalia. Palu noticed that they organized themselves into small platoons according to state. They carried pepper spray and baseball bats. Some of them confronted the photographer. “I got a drink poured over my head,” he recalled. “They called me names. Made death threats. The cops saw all this. None of them said anything.”

The president tweeted his approval of the gathering: “Didn’t know about this, but I’ll be seeing them!” Trump made good on his promise, flying over the throng in the Marine One helicopter on the way to the Army-Navy football game in West Point.

Palu’s experience in war zones led him to conclude that the Proud Boy event—which sparked clashes with counter-protesters throughout the city—was in a way a reconnaissance mission. They “were learning the city, learning what they could do, and what they couldn’t, figuring out how they could push it further,” he said. When the president announced that there would be a rally outside the White House on January 6, before Congress began the official tallying of the electoral votes, Palu knew that this was the push-it-further moment. His harrowing, too-close-for-comfort video of the melee at the Capitol was published on National Geographic’s website and on Instagram. In his photos from that day, he captures the agitated, frenzied mob as it masses outside the Capitol and then swarms hallowed halls decorated with paintings and statues representing the country’s democratic heritage.

But as these photographs make clear, the cause and effect of the president’s “fight like hell” exhortation and the rioting at the Capitol was not a spontaneous movement. Rather, the roller-coaster ride was set in motion much earlier, through a combination of authoritarian connivances and a relentless disinformation campaign. Palu sees July 25, 2019, as a turning point, when a seemingly routine phone call set up for Trump to congratulate the recently elected president of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelenskiy, took a startling turn. After Zelenskiy expressed his hope that the U.S. would make good on its stated intention to sell the Ukraine military some missiles for defensive purposes, Trump memorably responded, “I would like you to do us a favor, though.” He then named his price: investigate Biden, his presumed political opponent.

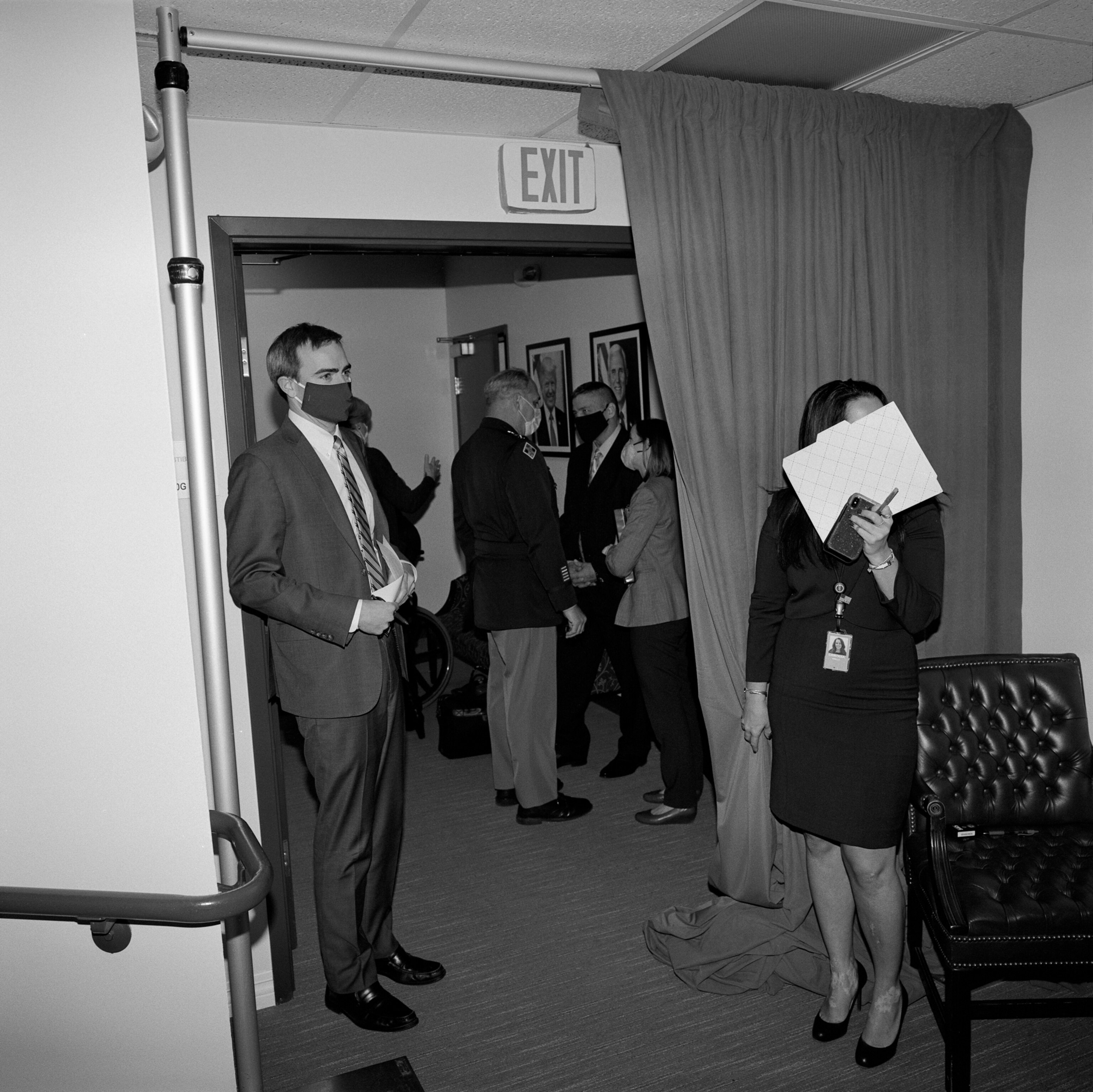

The cascade of events is now well known: a whistleblower complaint, Trump’s insistence that the call was “perfect,” impeachment in the House along partisan lines for abuse for power and obstruction of Congress, and acquittal in the Senate (with Senator Mitt Romney of Utah as the lone GOP dissenter). The president framed that vote as “total exoneration.” Palu captured both the drama (a government official enters a secure room for testimony) and pageantry (an aide arranges U.S. flags for a news conference) of the first impeachment. Emerging from scandal was a defiant incumbent of historic unpopularity yet still worshipped by his loyal base. To them, their leader’s reelection in November was assured. Defeat was only possible if Trump’s avowed enemies—the Democrats, the media, the alleged “deep state” burrowed into the federal bureaucracy, the RINOs (Republicans In Name Only) speaking out against him and the “China virus” unraveling the U.S. economy—conspired to steal it from him.

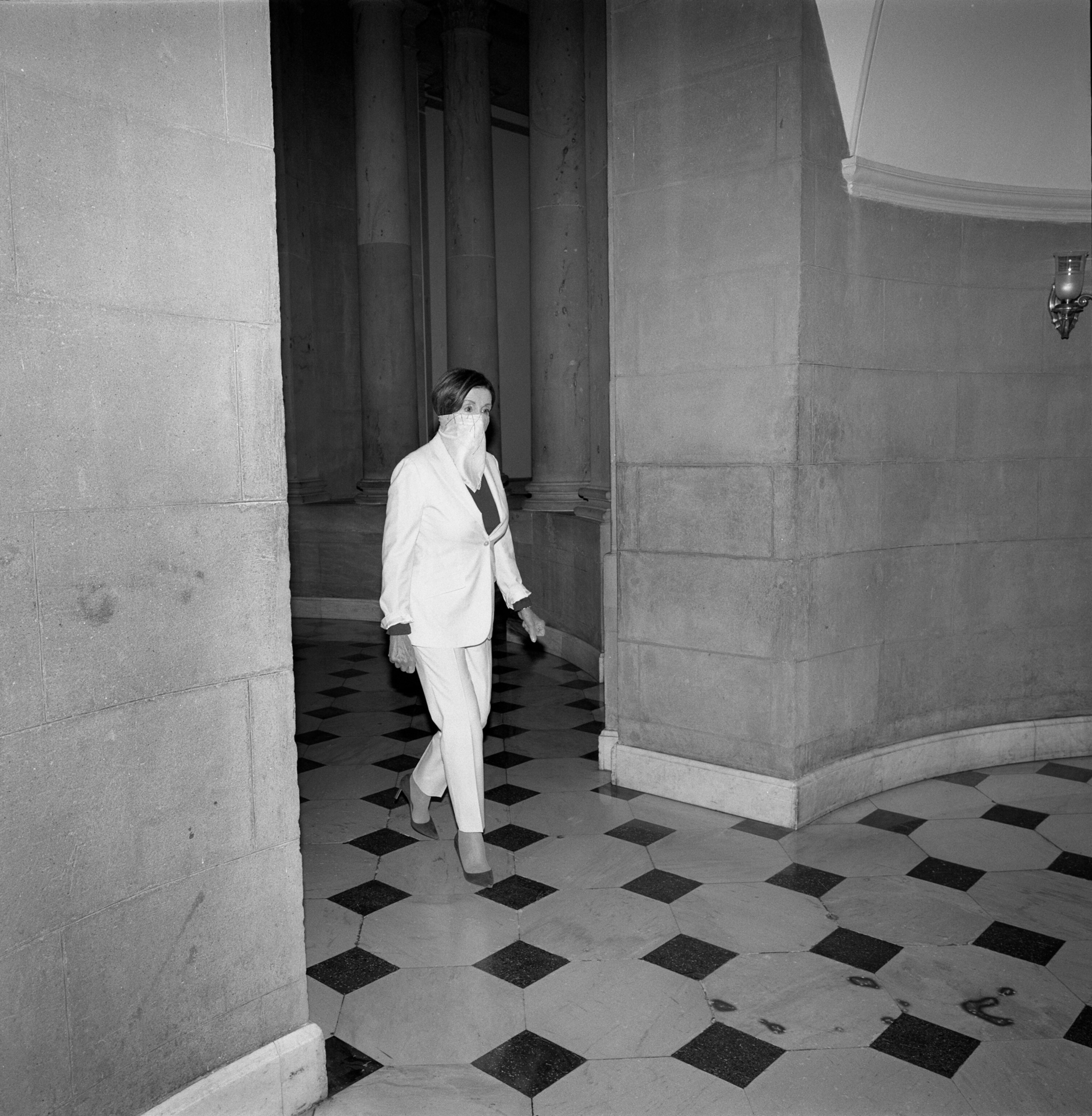

Palu’s visual depiction of this grim American narrative is shot in black and white. It is factual, stark, unambiguous, unforgettable. He focuses on the melodrama’s best-known actors—the president, his close advisers, his cheerleaders, and his antagonists. Taken together, the photos seem to show how Trump’s relentless attacks started a slow burn that finally ignited. What once appeared as vaudeville—the over-the-top assertions of a reality TV star—revealed something unsavory about America. This state of fracture is who we now are. And to amend America’s 45th president: We alone can fix it.