Here's What We Used to Think Dinosaurs Looked Like

These forgotten works of paleoart mingled scientific fact and fantasy.

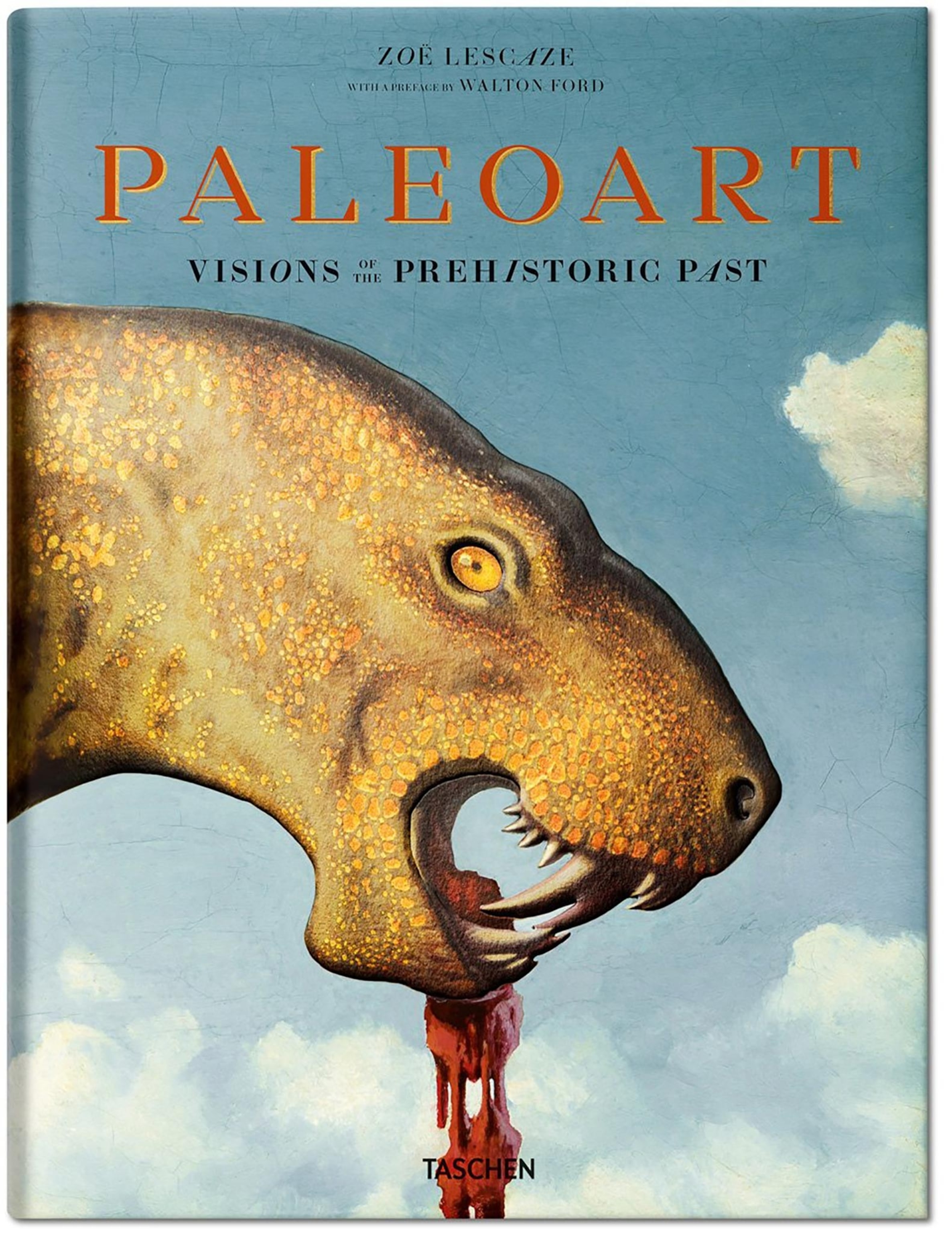

Since the first dinosaur fossils were discovered, the public has relied on artists to imagine what the prehistoric world looked like. Today many of the first “paleoart” masterpieces lie gathering dust in museum storage rooms, their creators forgotten. But these paintings once attracted large audiences, aroused intense controversy, and deeply influenced later visions of prehistory, from King Kong to Fantasia, as Zoë Lescaze explains in Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past.

Speaking from a Greek island during her summer holiday, Lescaze explains how these artists mingled scientific fact with fantasy, why the Soviet Union was such a big promoter of paleoart, and why, ultimately, these images of the remote past say something about us, and our future on the planet. [See our best idea of what a dinosaur looked like.]

Paleoart is a new term for me. What is it? Are these cave-paintings, like the ones at Lascaux?

No, that is the main confusion around the term “paleoart.” Paleoart is created by modern humans about the subject of prehistoric matter, whereas cave paintings, or Paleolithic art, were made in prehistoric times by prehistoric people.

Paleoart only began in the early 19th century and has rattled along as a genre since then, so it is relatively new. Part of what I find so fascinating about it is that, like everyone else in the world today, I grew up with images of what the prehistoric world looked like: enormous, blood-thirsty reptiles clashing on the battlefield with volcanoes going off in the background. These iconic confrontations, and the general tone of our understanding of the prehistoric world, are artistic inventions dating back to the 1830s, when artists began imagining what prehistory may have looked like.

One of the first, and most famous images, was Henry Thomas De la Beche’s Duria Antiquior. What’s remarkable about that painting is that, despite being the founding image of an entire genre, it’s a fairly unassuming watercolor. Today, it is housed in storage at the National Museum in Cardiff, Wales. It is not much bigger than a sheet of printer paper. Later natural history museums and other institutions started commissioning large-scale murals and oil paintings.

You write, “This is a book about the crossroads of art and science, cultural myth, and collective fantasy.” Can you break down those components for us?

Paleoart is interesting because it is at the intersection of art and science. The artists in the genre were looking at fossil evidence and reconstructing the prehistoric world based on this scientific evidence. Often the fossil evidence was scant, though, so there was lots of room for the artist’s imagination to fill in the blanks with fantasy, myth, and their own fears. The very first picture we have of prehistoric reptiles is a chaotic carnivorous fight scene where virtually every creature in it is chasing another one, or getting eaten. That has carried over into our contemporary understanding of prehistoric animals and how they interacted.

In the early days of paleontology, artists inevitably infused the genre not only with their own personal predilections and aesthetic preferences but with broader cultural aspirations and anxieties. A dinosaur painted in Soviet Russia looks very different from one painted in the Gilded Age of America or in Occupied France. In many ways the fossils served as tabula rasa upon which artists project many other narratives.

How did the public react to these images when they first appeared? I am thinking of Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins’ exhibition at the Crystal Palace in England.

Prior to the work of Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, most images of dinosaurs and the prehistoric past appeared in costly scientific publications or as the front-pieces to books most people couldn’t afford, or would not want to read in the first place.

Then in 1854, when the Crystal Palace was being re-built, Hawkins, who was a natural history illustrator, was asked to create the first life-sized sculpture of prehistoric reptiles. Not only are they the first three-dimensional reconstructions of prehistoric animals, they’re at life size. So you have this monumental impact on the public imagination.

These sculptures, which you can still see today, are what introduced mass audiences to what were then very threatening concepts of extinction. Today we are so used to hearing about extinction and climate change that it’s difficult to put yourself in the place of someone who assumes all animals were created by God on the same day, and all the ones that had been created were still around, and would be forever.

People who see the installations today tend to comment on how utterly whacked they look. Not at all like the dinosaurs we know and love today. They’re oddly mammalian. The reason for that is that they were weapons in an ideological crusade against evolution. The artist’s scientific advisor was Richard Owen, a brilliant anatomist, who unfortunately is mostly remembered for his rejection of evolutionary theory. For him, the pictures became a mass spectacle through which he could force his views about evolution onto the public. In order to combat the theory that animals become more advanced over time, he needed the dinosaurs to look more advanced than contemporary reptiles. So he urged Hawkins to create these big, scaly rhinos.

Across the Atlantic, paleo art became the subject of a phenomenon called the “Bone Wars.” Tell us what happened—and how the American vision of prehistory differed from the European one?

The Bone Wars was this fascinating period in the 19th century when American paleontologists were racing out west to discover new species. The field is dominated by two scientists, Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope, for whom science became almost an afterthought to their competition. They would dynamite big pieces they couldn’t haul away from site just so they couldn’t fall into the hands of a competitor.

U.S. paleontology in the 19th century was characterized by this ruthless, insatiable appetite. It’s during this period that we get so many of the species that are most iconic today, like T. rex or brontosaurus. And it was that atmosphere of competition and larger than life egos playing out on a massive scale that infused early works of American paleo art.

For many Americans, dinosaurs were also oddly wrapped up in the poignancy of the disappearing Wild West. As one historian has argued, much like cowboys, dinosaurs are big, strong, and formidable—but they’re also extinct and therefore impotent. It’s that combined power and obsolescence that makes them attractive.

You call the painting “Horned and Carnivorous Dinosaurs,” by American Charles R. Knight, “the single most influential work of paleoart, which still echoes through painting animation and film.” Tell us about the picture—and its legacy.

I urge everyone to visit the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago and see it. It’s a massive, 25-feet-wide oil-on-canvas painting that completely fills your field of vision. In it, a T. rex is charging a triceratops, meeting one another on the Cretaceous battlefield, not unlike Hector and Achilles or other iconic enemies.

This high-noon standoff resonated with many other artists, particularly animators working in the early 20th century, like the stop-motion animations of Willis O’Brien or Ray Harryhausen. The T. rex in King Kong, which came out in 1933, around the same time as the painting, is also heavily based on Charles Knight’s T. rex as are the dinosaurs in stop-motion animations. In Fantasia, a whole animated sequence is based on that painting, though in that case it is a T. rex versus a stegosaurus, but what can you do?

I was surprised to discover that paleo art reached its apogee under the Soviet regime. Why did Soviet society become so fascinated with pre-history and dinosaurs?

These Russian works, many of which have never been professionally photographed before, are fascinating because they reflect a Stalinist culture of monumental decoration. Some of the pieces shown in the book are without precedent anywhere in the world: 100-foot-tall mosaics and murals longer than subway cars.

Paleo art from the Soviet Union is interesting because the artists creating it had more expressive freedom than the official fine artists working at the time. As a fine artist, you were subject to censorship and forced to produce didactic images of happy steel workers and peasants. Whereas paleoartists, working in the venerated realm of science, had less restrictions.

It’s tied to the Soviet tradition of monumental decoration and the communication of information through vastly impressive means.

You can find massive murals of astronauts and other scientific fields, so paleoart isn’t the exception. It’s one of many disciplines that achieved new levels of conspicuousness and support under an atheistic Soviet Regime.

Most of the artists who created these works have been long forgotten, and their paintings locked away in dusty storerooms. Why is that? And why is it important that we remember them?

It’s important to remember and reexamine scientifically obsolete works of paleoart because of how much they tell us, not just about how scientists viewed a particular species at a given moment, but about the context in which they were created. Like many other forms of illustration and visual culture that aren’t works of fine art, paleoart has been rather neglected, but today scholars are reexamining it in a new light instead of writing it off.

Sadly, paleoart is vulnerable in a way other forms of natural history illustration aren’t because images are regularly outdated by new fossil discoveries. For example, almost all older works of paleoart depict dinosaurs dragging their tails on the ground. But after fossilized tracks revealed that dinosaurs held their tails aloft, probably for balance, every illustration or painting that shows a dinosaur with its tail on the ground is no longer accurate.

In the hands of a museum director who wants to make some space in the storerooms, these works are threatened. Some I saw over the course of my research have only been preserved because museum employees quietly fished them out of dumpsters, despite instructions to destroy them. If this book does anything, I hope it may attract a little more attention and regard for these images that, even if they’re not scientifically accurate, are still a really valuable record.

Ely Kish, an American artist who emigrated to Canada, is a good example. She worked primarily in the 1970s, when scientists were first becoming aware of climate change, and her works reflect that. She created numerous apocalyptic scenes of dinosaurs struggling through drought-afflicted landscapes, with dinosaur corpses lying beneath exploding suns.

Among the scientific community she had certain recognition. But I had never heard of Ely Kish, despite being into this stuff, before I started researching the project, even though she did a giant mural at the Smithsonian Museum and illustrated a number of popular science books. Like other works of paleoart, her paintings are a lens into how we humans regard our longevity on this planet—and our own chances of survival.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.