How a new pope is elected

Who gets a vote? What do those smoke signals mean? And is there really as much intrigue as depicted in Hollywood? Here’s what you need to know about papal succession.

With the death of Pope Francis at the age of 88, the world will now turn to a pressing question: Who will be the next pope—and how will he be elected?

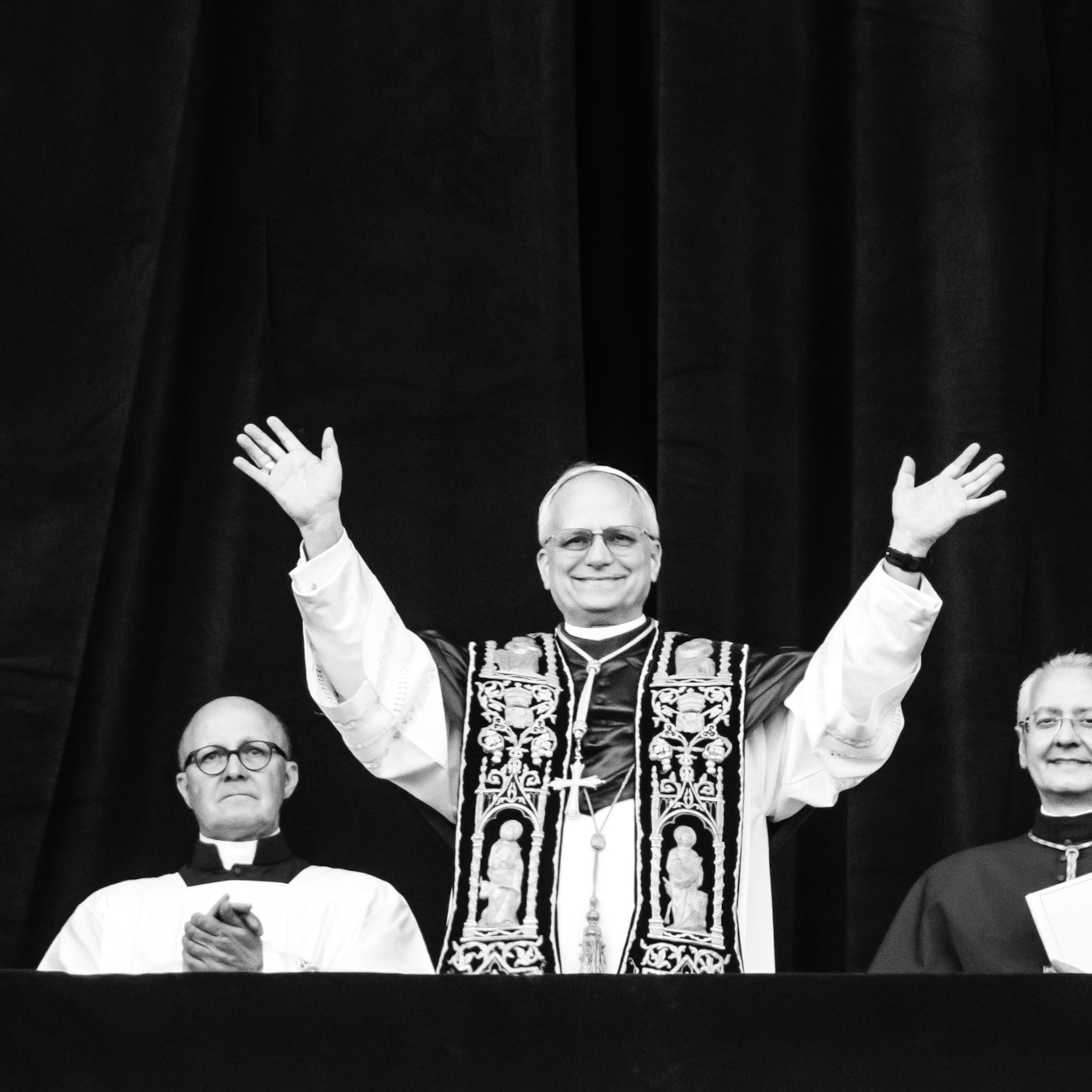

(A new pope has been chosen. Read how he is making history.)

After Pope Benedict XVI’s resignation in 2013, it took two long weeks for the Catholic faithful to find out who would be their next representative of God on Earth.

Crowds in Saint Peter's Square at the Vatican let out a cheer as the white smoke from burned ballots signified a successful vote among the members of the College of Cardinals. It was the final act that sealed the intricate papal selection process that allegedly dates back to the time of Jesus Christ.

Here’s a closer look at the real story behind one of the Vatican’s most mysterious and time-honored processes.

What are the origins of the papacy?

The pope was originally the bishop of Rome, a position first held by Saint Peter (one of Jesus’ 12 disciples), according to the Catholic Church. The Petrine theory states the authority given to Peter from Christ (when he took the position in A.D. 30) has subsequently been handed down to each pope since his tenure.

(The centuries-old Catholic doctrine that encouraged colonization.)

Peter was considered a papa, a Latin term used by Christians out of filial respect. At the time, the same title was used by esteemed churchmen throughout Christendom. The exclusivity over the word papa—from which "pope" derives—was not claimed by the bishop of Rome until the sixth century. Papal primacy, the concept that the pope is the church’s highest leader, became inextricably linked to the papa in Rome, elevating the bishop of the city over all other bishops.

How did we come to today’s process of papal succession?

Popular opinion, both of clergy and worshippers, was used to elect popes until the 11th century. Obviously, there was rarely a consensus. This led to disputed elections and antipopes—individuals with substantive, albeit false, claims to the papal seat.

Pope Nicholas II issued a decree in 1059 articulating the process by which popes would be elected going forward, outlining the role of cardinal bishops as the electors. Nicholas II himself took the position between two antipopes, showing just how contentious papal succession was. The decree of 1059 lessened the influence of the Roman aristocracy and lower clergy and laid the foundation for the College of Cardinals, formally established in 1150.

Criteria for candidates, voting regulations, and the need to sequester electors were formalized, only to be altered and adjusted as flaws in the system became clear.

The need for a two-thirds majority vote began in 1179. The number of cardinals went from no more than 30 during the later Middle Ages to 70 in 1586. More than four centuries later, Pope Paul VI set the maximum number of voting cardinals to 120 in 1975. The current age limit for voting cardinals was set at 80 years of age in 1970. With every pope, the number of cardinals increases—today, there are 222 cardinals with 120 eligible to vote. By the end of the year, eight more will be ineligible to vote as they celebrate their 80th birthday.

When a pope dies or resigns, all members of the College of Cardinals are obligated to attend the election (called the conclave), barring poor health or exceeding the age limit. Resignation is the exception rather than the rule, however. Before Benedict XVI's resignation in 2013, the last pope to resign did so in 1415.

Once the papal see is vacant, the official papal conclave begins within 15 to 20 days of the last pope’s departure. This length of time was established in 1922 to allow cardinals sufficient time to travel to proceedings.

How is a pope chosen today?

Cardinals are all electors of the next pope—and technically all of them are candidates too. When the cardinals arrive in Rome, they are each assigned a "titular" local church to oversee and hold Mass at during their stay. It's also an avenue by which cardinals make their faces and names known to the world.

Akin to a final campaign stop for a politician, the Sunday before a conclave makes for "an odd scene" according to author and papal expert John Thavis. Thavis explained in 2013 that papal contenders are "very careful not to say anything that appears to be campaigning."

Once the College of Cardinals officially convenes, they are sealed in the Sistine Chapel until a new pope is chosen (barring extraordinary circumstances). They swear an oath to maintain the integrity of the conclave—secrecy is of utmost importance and only a few attendants are allowed to have any contact with voting cardinals.

Preparation of the ballots (called “pre-scrutiny”) involves distribution, completion, and the designation of ballot collectors and counters. Casting one's vote (“scrutiny”), is done in secret.

During “post-scrutiny,” votes are tabulated, reaffirmed, and then burned.

An initial vote takes place on the first day. If no one is elected, a maximum of four votes for each subsequent day of the conclave is held, with each unsuccessful group of ballots burned afterward. If three days of voting offers no new pope, members of the conclave take a full day for prayer and contemplation. If that four day cycle repeats seven more times, a run-off between the two candidates who received the most support is held.

The burning of ballots, or fumata, is the public's clue as to what has actually taken place within the confines of the Sistine Chapel during the conclave. In order for smoke to be seen at all, a temporary stove and chimney are installed in the Sistine Chapel before the conclave starts. It's not entirely clear when the practice of burning ballots began, but white smoke as a sign of a new pope only traces to the late 19th or early 20th centuries. An unsuccessful ballot, when burned, sends off black smoke.

Until 2005, the Vatican added natural materials like wet straw (for white) and tarry pitch (for black) to the ballots. It wasn't until 2013 that the Vatican revealed the chemicals they adopted in 2005 for the purpose: a mix of potassium chlorate, lactose and conifer resin for white, and potassium perchlorate, anthracene and sulfur for black.

Four plumes of black smoke were seen in 2013 before white smoke finally appeared. Mere hours before that white smoke rose from the Vatican, a solitary white seagull perched itself atop the chimney. Observers took this to be a hopeful sign that the wait for a new pope was nearly over. They were right. Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio (Pope Francis) had been elected to the position by his peers.