How vaccination became 'hip' in the '50s, thanks to teens

American teenagers were a new social phenomenon, and uniquely poised for an iconic polio vaccine push.

It was a Saturday night in Albion, a small city just east of Battle Creek, Michigan, and teenagers lined up for a dance at the school gym.

The price of admission? A bared arm.

The year was 1958, and this was no ordinary Saturday night social outing: Billed as a “Salk Hop,” it was only open to young people willing to receive a jab of the polio vaccine developed by Jonas Salk, or show proof of vaccination.

The dance was part of a five-year war on polio vaccine hesitancy, a campaign that brought together the scientific know-how of public health experts with the burgeoning energy, creativity, and even sexuality of a powerful new presence in American society—teenagers.

Poliomyelitis, an infectious, virus-induced illness that could lead to paralysis, disability, and even death, didn’t become a widespread problem in the United States until the early 20th century. Before then, citizens were regularly exposed to poliovirus through unsanitary drinking water, boosting their natural immunity. Mothers also passed on immunity to their children through breast milk.

The modernization of sewage and water systems, however, meant fewer people were exposed and left children particularly vulnerable to infection. And the baby boom of the late 1940s and early 1950s set up the perfect conditions for widespread polio transmission. Suddenly, immunity was no longer a given, and tens of thousands of cases—mostly in children—began to appear every summer, possibly as a result of seasonal fluctuations in new births.

The result was panic, especially among parents. Pools and drinking fountains were closed every summer to prevent the virus from spreading. Terrified adults watched their once-active children rely on crutches to support weakened limbs, or even face confinement in massive iron lungs to facilitate breathing. Polio outbreaks picked up speed in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, peaking with nearly 58,000 cases in 1952.

Then came a breakthrough in the form of Salk’s polio vaccine, which was approved in 1955. Case numbers plummeted as more and more children were vaccinated. But though children lined up to take Salk’s vaccine in massive drives, teenagers were decidedly slower to line up for a shot. (Parents and social media will help determine whether members of Gen Z get their COVID-19 shot.)

'Almost indestructible'

Part of the teen vaccine-messaging issue came down to terminology. For years, people had referred to polio as “infantile paralysis,” stoking the impression that teens and adults weren’t at risk. Then there was the perceived inconvenience of the three-dose vaccine regimen, and some feared needles or the vaccine itself.

“All of a sudden, the vaccines weren’t just for responsible adults or young children. They were for cool teenagers.”

Stephen Mawdsley, Social historian and lecturer in modern American History at the University of Bristol in England

“Teens felt healthy, almost indestructible,” says Stephen Mawdsley, a social historian and lecturer in modern American history at the University of Bristol in England. In reality, they were anything but—and for protection from the virus, they needed the vaccine.

But the same social forces that made adolescents feel (wrongly) more resilient than their younger counterparts ended up becoming a secret weapon against polio.

(What to know about teenage brains)

Before the turn of the 20th century, teenagers weren’t recognized as a social group of their own. Subsequent changes in American society, including the rise of the automobile and compulsory education that kept children from entering the workforce early, sparked recognition of teenagers as a distinct U.S. demographic. “They live in a wonderful world of their own,” trilled a 1944 edition of LIFE in an article devoted to adolescent girls and their fads.

In response to the vaccine lag in teens, the National Institute for Infantile Paralysis, a polio non-profit that distributed funds raised by the March of Dimes, recruited directly from that reluctant demographic. In 1954, the organization began inviting select groups of teenagers to their New York offices, interviewing them on their perceptions and reservations about the vaccines, and equipping them with talking points to promote Salk jabs back home. (Related: A “polio warrior” recounts decades of struggle toward eradication.)

Mawdsley says the teens were motivated by personal experiences with polio survivors and victims, a desire to support causes they cared about, and a search for social empowerment.

“They were in a phase of life where they wanted adults to respect them,” he says.

Peanuts for polio

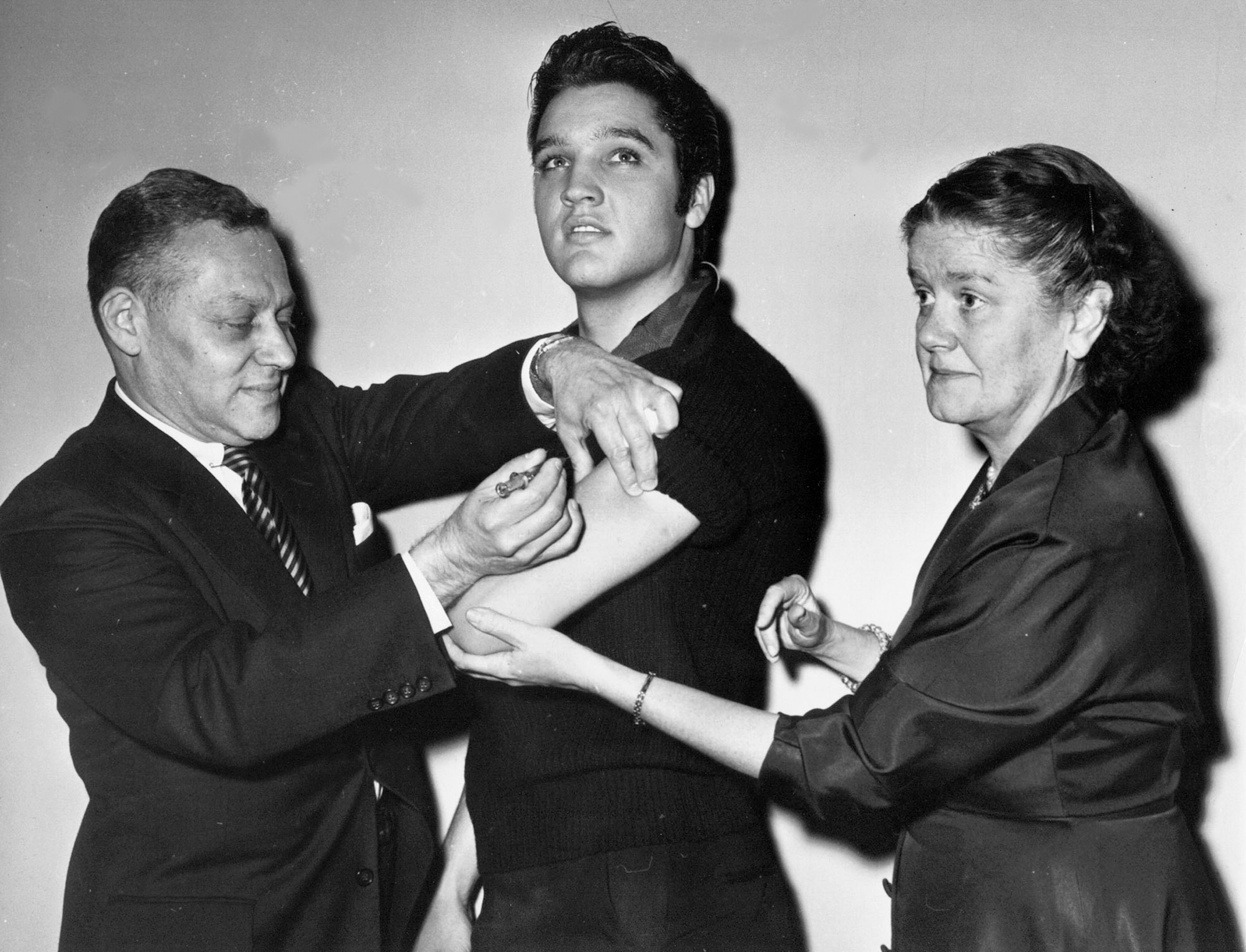

The teenage war on polio took on several forms. While officials recruited teen idols like Elvis Presley and Debbie Reynolds to spread the word via public vaccination campaigns, adolescent vaccine ambassadors became celebrities in their own right as they participated in grassroots vaccination efforts that often resulted with their names and photos in print. They sold “Lick Polio” lollipops and “Shell Out for Polio” peanuts to raise money for the March of Dimes, and wrote impassioned letters urging teen vaccination for the editorial pages of local newspapers.

Even teen libidos were leveraged for the polio vaccine effort. “Some of us girls have talked about not dating fellows for certain activities, if they haven’t had their polio shots,” said Patty Hicks, the national chair of Teens Against Polio, in 1958. The “vivacious, dark-eyed ‘brownette,’” as Hicks was described by the Spokane Chronicle, encouraged other girls to do the same.

There was a dark side to the national push to vaccinate American teens: ableism. By marketing the polio vaccine essentially as a way to stay able-bodied, it stigmatized polio survivors in the process. Eventually, however, the activism of those survivors helped to fuel the disability rights movement, which led to the 1990 Americans With Disabilities Act.

Though it’s hard to quantify how much of an effect teen activism had on acceptance of the polio vaccine, Mawdsley says, their advocacy helped transform attitudes toward the virus. “All of a sudden, the vaccines weren’t just for responsible adults or young children. They were for cool teenagers.” As a result, teen uptake increased in the late 1950s. (Brazil once vaccinated 10 million people for polio in a day.)

Advances in polio vaccines helped as well, and a less-expensive, single-dose vaccine replaced the three-jab Salk vaccine in the 1960s. Since 1979, no polio cases have originated in the United States, and in 2016, there were only 42 cases of polio worldwide. While the coronavirus pandemic, as well as conflict in places like Afghanistan and Pakistan, likely drove up polio numbers during 2020, polio vaccination is now seen as standard.

More than 60 years have passed since “Salk hops” swept the nation, and now the United States is in another national vaccination push in the race to staunch cases of COVID-19. But vaccine hesitancy remains in some populations, and—in an echo of the mid-20th-century polio vaccination push—the Biden administration recently announced it plans to use celebrities, athletes, and social media to target teens eligible for coronavirus vaccines.

Political, social, and generational echo chambers fuel vaccine hesitancy. The teen vaccination “fad” of the 1950s and 1960s offers lessons on how to leverage that insularity on behalf of public health.

“We need to identify the groups that are hesitant and recruit from within their ranks, educate them, and send them back with messages to inform them,” Mawdsley says. “Otherwise we’re not going to break in.”