How white planters usurped Hawaii's last queen

The bloodless but brutal coup brought Hawaii's monarchy to an end—and paved the way for U.S. statehood.

In her Honolulu palace, Liliʻuokalani wavered over the piece of paper that, once signed, would remove her standing as the country’s queen. If she abdicated, six of her most ardent supporters would be released from the prison where they awaited execution for treason. The men had rallied a small army of fewer than a hundred to defend her position as the ruler of Hawaii, but after a few unsuccessful skirmishes, they had stood down.

“For myself, I would have chosen death rather than sign it,” she wrote in her autobiography. “Think of my position…the stream of blood ready to flow unless it was stayed by my pen.”

With her signature on January 24, 1895, generations of a Hawaiian monarchy came to an end. The islands Liliʻuokalani once ruled would soon be annexed by the United States at the behest of white settlers who had come to see Hawaii as a cash cow. The legacy of that loss to a wealthy minority still resonates today.

A sugar boom leads to political crisis

Historically, each island had been ruled by a hereditary chief. After the first European explorers arrived in 1778, contact with the outside world brought trade opportunities and advances like a written language. A warrior named Kamehameha from Hawaii Island—also now known as the Big Island—took advantage of the weapons they had brought to wrest control from most of the islands’ chiefs. He united the Hawaiian Kingdom under a constitutional monarchy in 1795, ending years of interisland conflict. As a united nation, Hawaii was better insulated against a potential takeover by foreign interests.

Those interests also decimated traditional Hawaiian society. Introduced diseases ravaged Native Hawaiians, and by 1840 their population had declined by a stunning 84 percent. The new constitutional monarchy, which mirrored European concepts of government, also reshaped long-held social structures.

The islands were increasingly populated by Europeans, from missionaries to American entrepreneurs who began acquiring land for sugar plantations. The plantations needed large numbers of workers, and owners began to import low-wage contract workers from around the world, especially East Asia. Soon, Hawaii was churning out massive amounts of sugar. In 1874, it exported nearly 25 million pounds of sugar to the United States.

Hawaii wasn’t just an economic powerhouse: It was seen as strategically important for its location between Asia and the U.S., which sought a foothold in the Pacific. Sugar planters paid steep duties on imports to the U.S., and the newly installed king Kalākaua agreed to cede some Hawaiian land—Pearl Harbor, on Oahu, and an islet now known as Ford Island—in exchange for the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875, a free trade agreement that removed taxes on sugar and other Hawaiian imports.

U.S. investment in sugar boomed. But so did U.S. interference in Hawaiian affairs. In 1887, a group of influential white sugar planters led by attorneys Lorrin Thurston and Sanford B. Dole took advantage of a spending scandal involving Kalākaua to demand—at gunpoint—that he sign a new constitution stripping the Hawaiian monarchy of most of its power.

Known as the Bayonet Constitution, the document allowed foreign residents to vote and restricted the suffrage rights of Asian workers and those who had low incomes or did not own property. Suddenly three out of four Native Hawaiians could no longer vote. Though they were still a minority, the white planters who called themselves the Hawaiian League effectively controlled the islands.

In the 1890s, economic and political crises roiled Hawaii. The U.S. passed legislation that removed sugar tariffs for other countries that competed with Hawaii’s sugar industry—and the price of sugar dropped dramatically. Hoping to stabilize the economy and regain a competitive advantage, the planters began petitioning for the U.S. to annex Hawaii.

A bloodless coup

In 1891 Kalākaua died, and his sister, Liliʻuokalani, took the throne. In 1893, she attempted to replace the Bayonet Constitution with one that would strip resident aliens’ voting privileges and strengthen the monarch’s power.

In response, Thurston and an armed group that included foreigners and Hawaiian subjects gathered within view of Liliʻuokalani’s palace and demanded she step down. U.S. diplomat John Stevens sent U.S. Marines to Oahu to protect American interests. Liliʻuokalani ordered her royal guard to surrender, and the coup leaders declared the monarchy abolished, established martial law, and hoisted the American flag over the palace.

It was a bloodless coup, and at first it looked like the provisional government, led by Dole, would secure a speedy American annexation of Hawaii. President Benjamin Harrison even signed an annexation treaty in February 1893.

But when Grover Cleveland became president less than a month later, he withdrew the treaty and sent special commissioner James H. Blount to the islands to investigate the coup. “The undoubted sentiment of the people is for the Queen, against the Provisional Government and against annexation,” Blount wrote in his report.

Calling the coup a “serious embarrassment,” Cleveland recalled Stevens to the U.S. and instructed his new minister to reinstate the queen. Convinced she would be backed by the U.S., Liliʻuokalani initially insisted that the coup participants be punished under the kingdom’s laws. But Dole contended his provisional government was legitimate and that only force would remove it. He refused to step down, and the U.S. took no further action against the insurgents. Though Liliʻuokalani maintained her right to the throne, she did not stand in Dole’s way.

In December 1893, the U.S. Congress began its own investigation into the coup. The Morgan Report, their answer to Blount’s report, was unabashedly pro-annexation and, in the words of historian Ralph S. Kuykendall, “managed to exonerate from blame everyone save the queen.” Congress did not follow the report with action, and Dole’s provisional government hastened to consolidate its power. In July 1894, the Republic of Hawaii was founded, with Dole as its president.

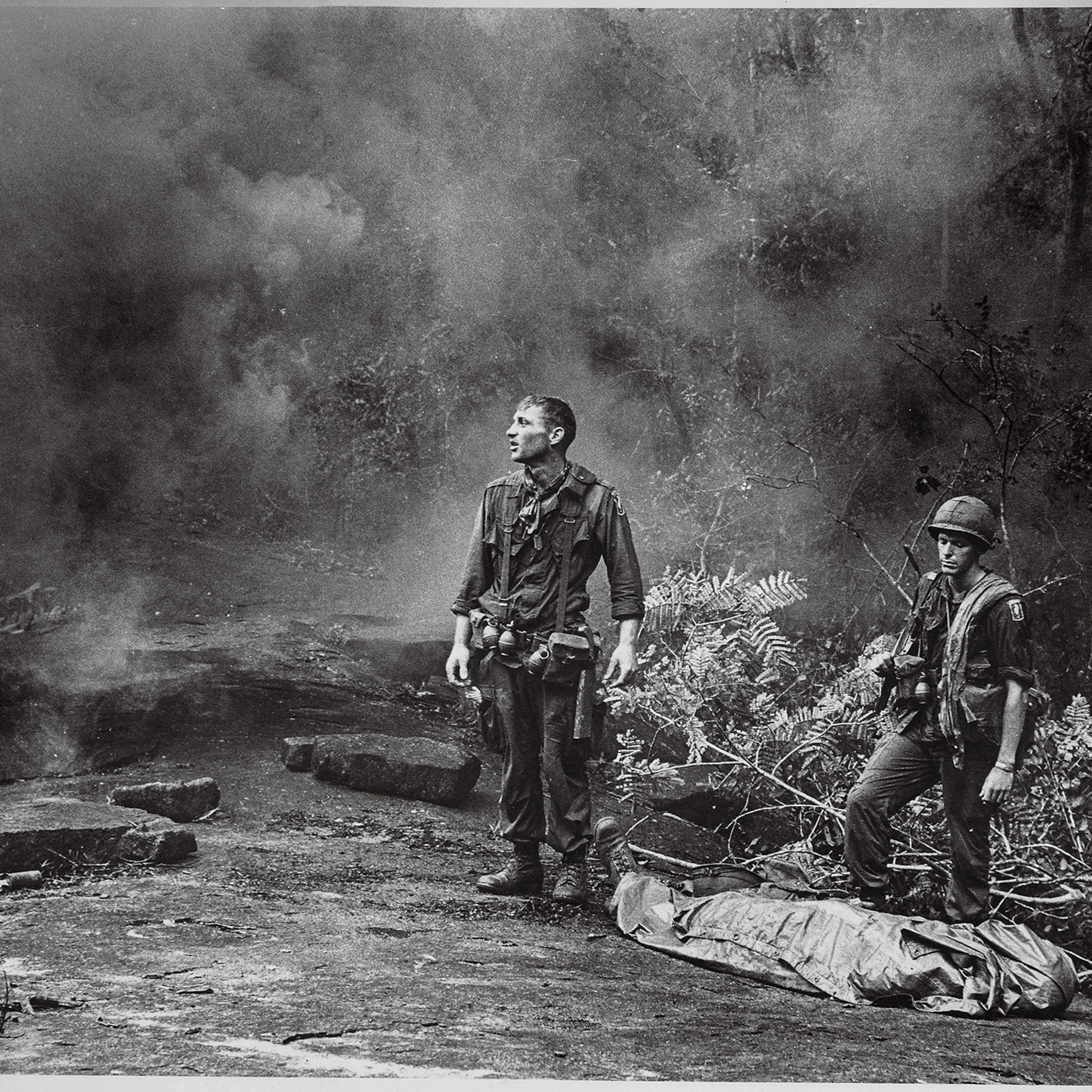

Six months later, a group of royalist rebels led by Hawaiian Robert W. Wilcox made an unsuccessful attempt to restore the monarchy in January 1895. He and co-conspirators had hoped to muster at least a thousand Native Hawaiians and other residents, but managed to recruit only a hundred or so. The counter-revolution was disorganized and ill-fated, and the men staged three brief battles before surrendering to police. One hundred and ninety-one suspected conspirators were arrested after the counter-revolution stood down, and Liliʻuokalani was arrested and tried for conspiring with them after weapons were found in her home. She officially abdicated in exchange for the freedom of six of her supporters who had been sentenced to death. Though she was sentenced to five years’ hard labor and fined, she remained under house arrest instead. In 1896 Dole pardoned her.

U.S. annexation

Cleveland’s administration had been unwilling to use force to take Hawaii back from the Americans who had seized it. When the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898, the new president, William McKinley, eager to gain a strategic advantage for the U.S. Navy by increasing its ability to refuel in far-flung waters, made good on his campaign promise to annex the islands. He called for a joint resolution in Congress, and in August 1898 Hawaii became a U.S. territory. It would remain a territory for another 61 years. In 1959, Hawaii became the 50th U.S. state.

And what of its overthrown queen? For years after her abdication, Liliʻuokalani attempted to regain her family’s land and receive restitution from the U.S. government. In 1911, nearly two decades after the overthrow of her monarchy, she was granted a lifetime pension from the Territory of Hawaii.

In 1993, the U.S. Congress adopted a joint resolution acknowledging that Native Hawaiians “never directly relinquished” their claim to sovereignty. The apology didn’t change United States policy, though. They are the only indigenous group in the United States without political sovereignty.

Today only about 10 percent of the islanders are of Native Hawaiian descent. Native Hawaiians face a number of health and social disparities, such as lower educational attainment, higher unemployment, and poverty, and higher rates of tuberculosis, smoking, and obesity compared to their white counterparts.

But pride in their culture is steadfast. In the 1970s, Native Hawaiians began a revitalized movement to maintain their language and traditional practices. This fed into a growing sovereignty movement that still seeks government recognition. “We are an independent, sovereign nation,” said Kaua’i teacher Kealii Holden during a 2014 public hearing on the issue. “There's a growing group of people that are becoming aware of the truth.”