How ice cream became a Prohibition-era craze

Confronted with the loss of booze, Americans comforted themselves with ice cream. Lots and lots of ice cream.

What was America’s favorite beverage during Prohibition? You might guess bathtub gin or home-brewed beer. But you’d be wrong.

“Prohibition made the chocolate ice cream soda the national drink,” declared a Wichita, Kansas, ice cream manufacturer in 1922. Recalling decades of ice cream production, he told The Wichita Beacon the national ban on alcoholic beverages had brought a boom to his business, turning ice cream from a once-in-a-while delicacy to a decided habit among customers.

He wasn’t alone. As Prohibition agents destroyed barrels of booze and bootleggers went underground, the United States turned to another addictive substance: ice cream. Here’s how America’s love affair with ice cream turned from a dalliance to a full-blown obsession.

The ‘legal heir of liquor’?

Ice cream had been in existence for centuries by the time Prohibition came along. Though its origins are unknown, the first ice cream parlor in the United States roughly coincided with the birth of the nation itself.

(When did we start eating ice cream? Here are the hypotheses.)

In an age without reliable refrigeration, ice cream was at first largely the realm of the rich. But advances in refrigeration led to the first commercial ice cream factory in 1851, then the creation of increasingly lavish ice cream parlors in urban centers. By World War I, ice cream was more available than ever, thanks to increasing electrification, more mass-produced foods, and growing cities.

But no one could have predicted the surge in ice cream interest brought on by Prohibition. While multiple states had already gone “dry” by prohibiting alcohol, the passage of the 18th Amendment in 1919 turned the entire nation into a teetotaling one. The result of decades of campaigning by reformers adamant that drink led to crime, domestic violence and other societal ills, Prohibition made it a crime to manufacture, sell, or transport “intoxicating liquors”—and sparked speculation about which addictive substance U.S. consumers would turn to instead.

“There seems to be a widespread impression that the candy industry is the legal heir of liquor,” wrote one observer in the Los Angeles Times in 1927. But though candy sales grew during Prohibition, it was ice cream that developed into a full-blown national craze.

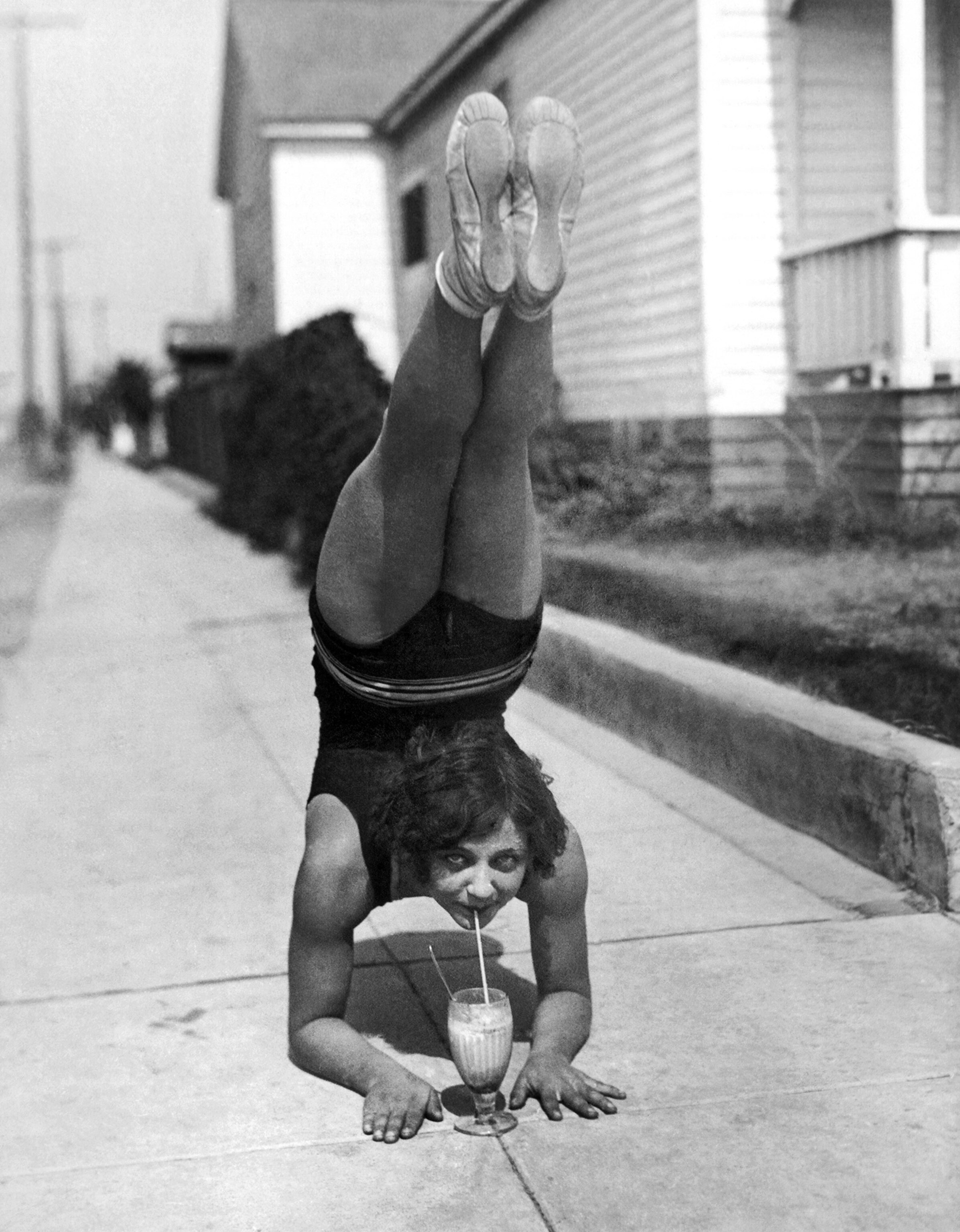

America’s ice cream spree

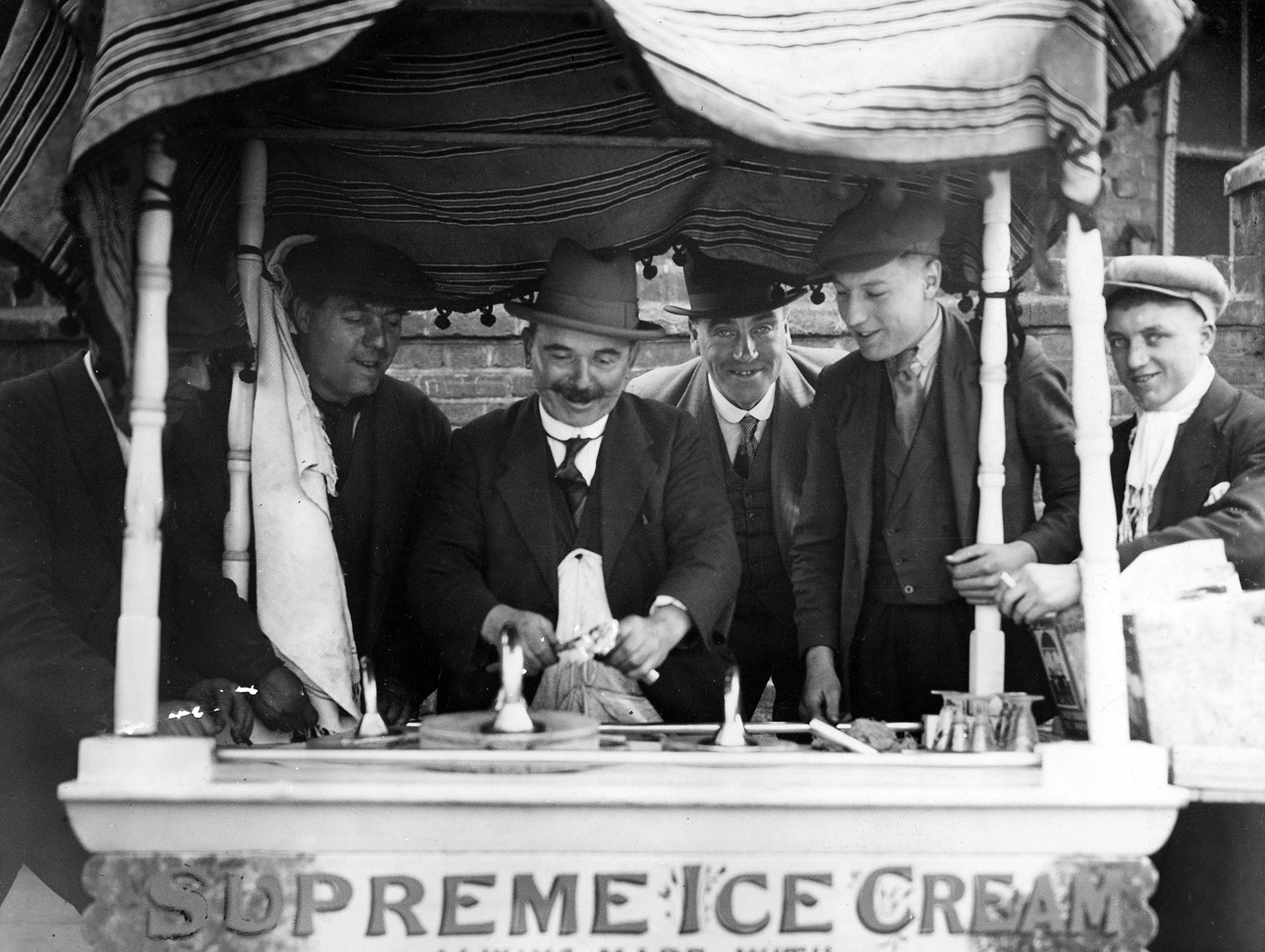

“America’s on an ice cream spree,” the secretary of the National Association of Ice Cream Supply Men told a reporter in 1922. That year alone, Americans consumed a whopping 325 million gallons of ice cream. People flocked to the counters of local drug stores for ice cream sodas, brought home cartons of the sweet, milky stuff to store in their new electric refrigerators, and took ice cream on picnics and to parties.

The demand for ice cream was so high that breweries with high refrigeration capacities began producing ice cream instead of beer. Anheuser-Busch sold ice cream with the slogan “eat a plate of ice cream every day.” Yuengling produced prepackaged ice cream with a handle, a design that saved ice cream vendors the grueling work of scooping large amounts of ice cream out of barrel-like containers into smaller vessels. The brewer produced a reported two million quarts a year by 1928.

Other breweries turned to making malt—a byproduct of grain fermentation and a vital ingredient for ice cream parlors—instead. Business was so good that in 1919 the Saturday Evening Post proclaimed that “When the brew-master turns from beer to ice cream he finds a field in which he can distinguish himself.”

Ironically, the same moral reformers who had called for an end to alcohol in the U.S. had also campaigned against ice cream parlors in the late 19th and early 20th century—warning that “white slavery,” sexual harassment, and prostitution could result from a visit to a lavish ice cream palace. But by the time Prohibition was enacted, reformers had moved on to other causes, leaving ice cream parlors to flourish.

(Women campaigned for Prohibition—then many changed their minds.)

And flourish they did, growing bigger, more common, and even developing their own soda-jerk slang, referring to soda water as “belch water” and malted milk extract as “hops.” For these wise-cracking ice cream scoopers, a chocolate malted milk with eggs was a “twist it, choke it, and make it cackle,” and an attractive woman waiting for ice cream was an “eighty-seven and a half.”

Ice cream bars and ice cream barges

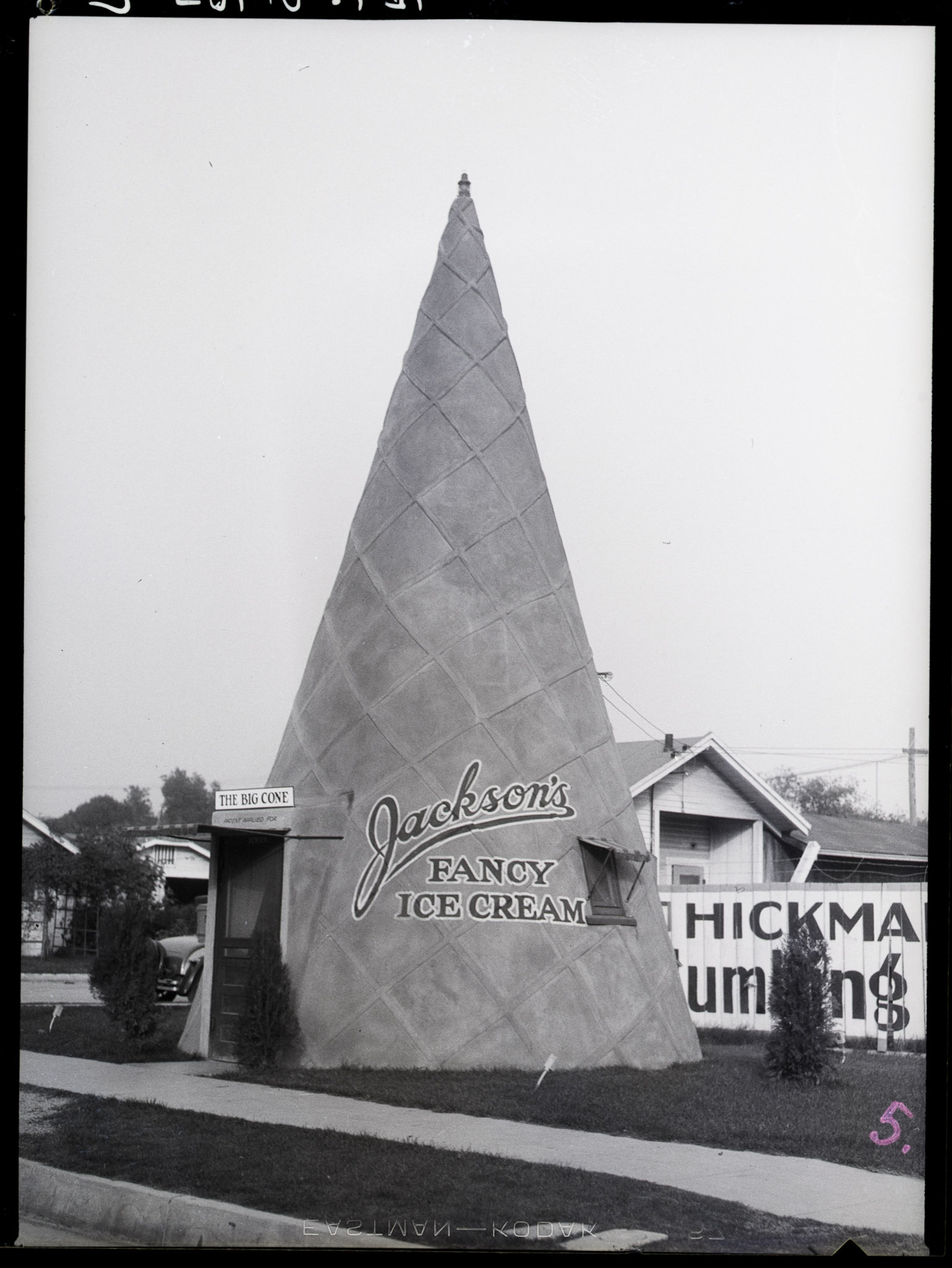

The boom led to innovation in ice cream, from the invention of the ice cream bar in 1920 to the creation of the ice cream truck, first popularized by the Good Humor company at the end of the 1920s. The surge in ice cream manufacturing was so intense that it sparked new laws, like a 1923 Pennsylvania law prohibiting false labeling of ice cream, flavorings and candy coatings containing “substance[s] deleterious to health,” and serving ice cream that had been stored alongside meat.

(Eight ice cream styles from around the world.)

The Great Depression, which began in 1929 and lasted through 1939, stymied ice cream production slightly. (It also sparked a new flavor, Rocky Road, whose contested history supposedly includes a name inspired by the “rocky” economic times.)

Eventually, the nation abandoned its attempt to curb alcohol consumption, and Prohibition was repealed for good in 1933. Historian Anne Cooper Funderburg writes that despite fears that the end of Prohibition might kill the ice cream trade, consumption actually rose after the repeal. Americans had learned to love ice cream, and the proliferation of roadside ice cream chains, street vendors, ice cream parlors, and cartons for home consumption meant it was easier than ever to get a sweet fix.

But perhaps the biggest testament to the influence of Prohibition on the popularity of ice cream can be found within the U.S. Navy, which had learned to love ice cream once alcohol was banned on ships in 1914. In 1945, the U.S. Navy created a million-dollar ice cream barge designed to supply a fleet of smaller ice cream ships in the Pacific theater of World War II with the creamy stuff. Ice cream distribution was considered a matter of “highest priority” during the war—proof that the sweet, cold concoction had become as American as apple pie.