75 years later, survivors of India’s violent partition return home—virtually

An innovative VR project brings victims of the largest forced migration in modern history back to the ancestral villages and cities they fled long ago.

In Jalandhar, the northwestern Indian city where Syed Sadiq Abrar was born, he was related to nearly everyone in his close-knit neighborhood: His grandmother lived next door to his great-aunt, and near a gaggle of cousins who’d play together, crisscrossing buildings via a seamless rooftop.

But when Sadiq, now 96, recently peered down Jalandhar’s crowded alleyways as the city’s inhabitants rushed past him on sidewalks, he felt unmoored. The retired engineer hadn’t set foot in his hometown since 1947. Yet here he was, seated on his plush beige couch in Fresno, California, next to his wife of 74 years, as they negotiated the streets of their childhoods—and the memories of everything they had lost—via sleek Virtual Reality (VR) headsets.

Sadiq was in his 20s in the summer of 1947 when India was released from two centuries of British colonial rule and divided into two nations: Muslim-majority areas in northwestern and northeastern India were carved out as Pakistan, while Hindu-majority India retained the bulk of what had been British India. The split, known as Partition, sparked one of the largest migrations in human history, as 15 million to 20 million people fled bloody ethnic cleansing campaigns across new borders, banishing families from the communities they had known for generations and centuries.

On the 75th anniversary of India’s Partition this August, there are few people left who can remember the dark period after the division. Thanks to 21st-century technology, a few survivors have returned—virtually—to the homes, cricket fields, snack shops, and schools of their childhoods. But after a lifetime of exile, going home isn’t always easy.

The making of a virtual return

Sadiq’s return to Jalandhar was one of nearly 20 “virtual returns” created by Project Dastaan, a peace-building organization founded in 2018 by four Oxford University students with roots in India and Pakistan, including Sparsh Ahuja, now a filmmaker and National Geographic Society Explorer.

In casual conversations, the students behind Project Dastaan noticed that their families had nearly identical stories: Ahuja’s grandfather fled from what’s now Pakistan into India during Partition; another’s grandfather was forced in the opposite direction. These two elderly men shared a wish to see their hometowns one last time. The enmity between Pakistan and India makes it hard to cross a once-nonexistent border, and after 75 years, their grandfathers, like most survivors of Partition, were simply too old to travel, and.

Explore the maps that show how the British split India in 1947.

So the students of Project Dastaan came up with an idea: a virtual return. They’d interview their grandparents, parents, and family friends to gather every detail of the childhood homes, from the trees they rested under to the markets they’d frequented. Then they’d travel to their respective sides of the border to match those memories with modern reality in 360-degree video. Later, back in the subject’s living rooms, a virtual reality headset would immerse their grandparents in that video, taking them “home.”

Word soon got out on social media, and what started as a personal project became a global initiative, with the hope to film 75 “returns” for the 75th anniversary of Partition—from a man who was a teenage political prisoner in the British colonial era to a 13-year-old girl forcibly resettled in Pakistan. The COVID-19 pandemic paused the project, but along with nearly 20 VR experiences, Project Dastaan has also produced an animated series on Partition and an animated VR documentary, Child of Empire, that enables viewers to experience Partition from the perspective of children, including Ahuja’s grandfather.

“Occasionally people say, ‘We’ve settled the past, why are you talking about this shared heritage? We’re Pakistani, and they're Indian, and that’s it,’” says Saadia Gardezi, a Pakistani journalist and one of the project’s co-founders. Each new generation has brought a fresh layer of separation and distance from life before Partition, she says, fortified by political stalemates and memories of old conflicts. “But it’s not been that long ago that we were literal neighbors in our home villages,” she adds.

Project Dastaan’s first interview was Ahuja’s grandfather, a Hindu who fled east from the province of Punjab in what is now Pakistan. He described hills outside his home village that would echo back when he yelled, and recalled the Muslim man who’d hidden his family from violent mobs during the chaotic days of Partition. When Ahuja traveled back to his grandfather’s village in what’s now Pakistan, he found the echoing hills and a son of the man who sheltered his grandfather’s family. Ahuja returned with a bit of soil from the village and the WhatsApp number for the son.

Information to create the VR experiences is gathered with a forensic attention to detail, to ease what could otherwise be a wild goose chase. Over 75 years, street names have changed, development has boomed, and residents who lived through the Partition are scarce. Sometimes a single tree is all that is recognizable in a village.

Seeing what has been lost from their childhoods can be painful, Gardezi concedes. “The memory we’re providing them is not their memory, it’s a different version,” she says. “It is very emotional experience we provide to people—and to ourselves.”

A surreal homecoming, 75 years later

As afternoon sun fills the living room, three of Syed Sadiq Abrar’s adult children watch as he takes in the scenes from Jalandhar through the VR headset. He sees the building his uncle once owned, the spot where he played cricket with friends. Down the alley is the fried-dough shop where the victors would treat the losing team. And here is the market where religious processions would parade through during a Hindu holiday every autumn. Had it shrunk, he wonders, or had his memory enlarged it over 75 years?

Partition came into effect at midnight on August 15, 1947, and what had been tremors of instability quickly escalated into mass slaughter. In many parts of India that had been divided, neighbors turned on each other and militias killed, tortured, and raped with a brutality some international observers compared to the horrors at recently liberated Nazi concentration camps. As many as one million to two million people were estimated killed. Among them was Sadiq’s grandmother, whom he later learned had been burned alive in her home in Jalandhar.

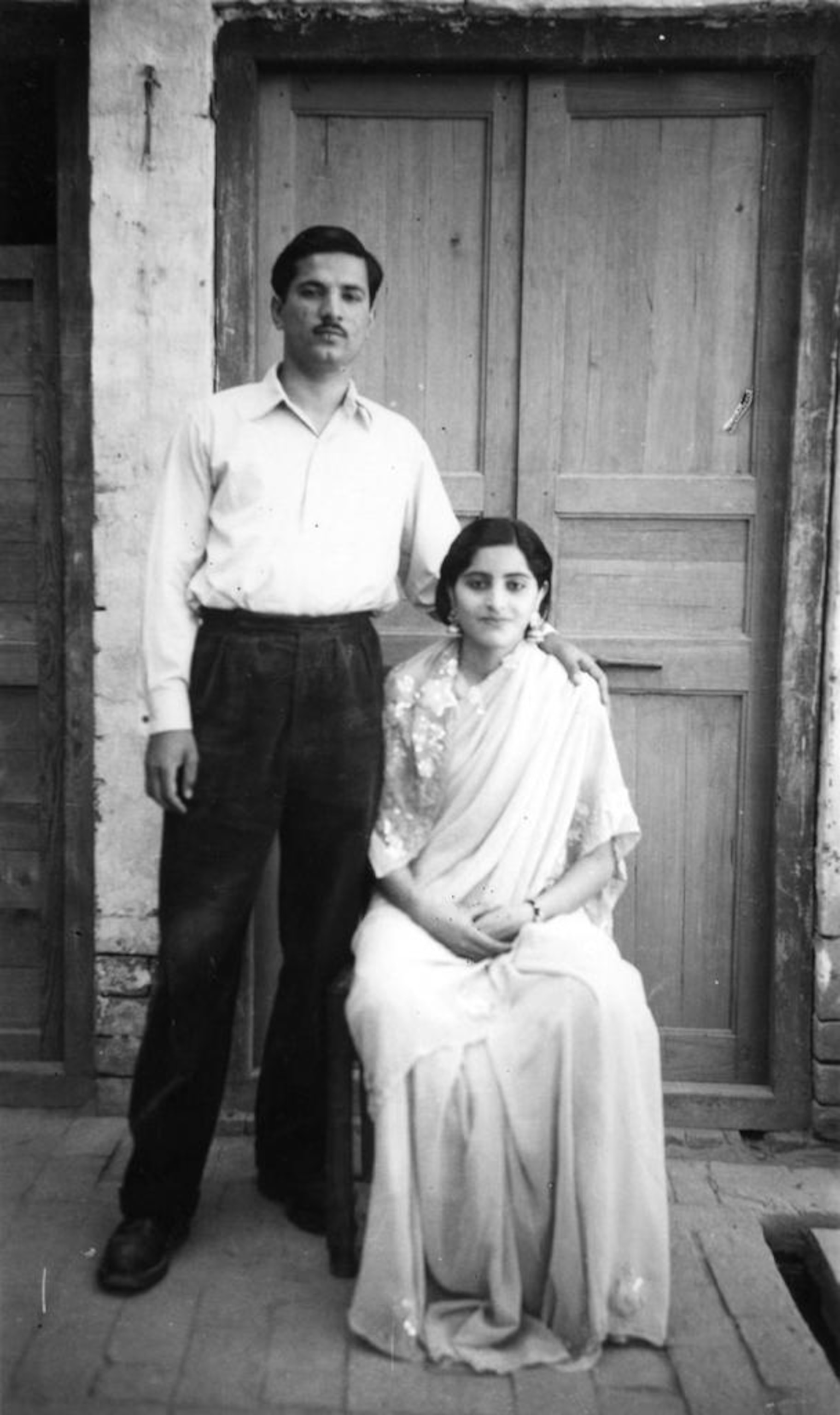

In his new country of Pakistan, Sadiq became an electrical engineer and married Syedda Musarrat, another refugee. They had five children and in the 1990s, they retired to Fresno to join one of their sons.

Seated next to her husband, her hands clasped around the VR headset, Musarrat is immersed in her return her hometown of Dhariwal, once famous for its high-quality textile mill.

On the morning of August 14, 1947, the city was peaceful, but soon unrest brewing in other regions reached there too. When the new flag of India was raised above the mill three days later, riots erupted.

Musarrat and her family joined thousands of other Muslim refugees trudging toward Lahore in the monsoon rains. At night they hid in friendly Hindu temples and police stations, moving each time they heard a mob coming, until they arrived a month later in what had become Pakistan. Musarrat’s parents, once landlords in Dhariwal, had to survive on scraps, the 92-year woman recalls. “We thought nothing is better than a piece of land: the safest possession of humankind that cannot be stolen.”

Neither Musarrat nor Sadiq ever spoke of Partition to their children, and for years she’d brushed off the urgings of younger family members to visit their childhood hometowns. “Who would like to live in bitter memories?” Musarrat wonders. “The sooner you forget, the better.”

Now, as she takes off the virtual reality headset, she seems dismayed by the toll 75 years had taken on Dhariwal. Though the famed mill still bears the name of the British India Corporation, foliage grows from its broken windows—a far cry from the prosperous industry that once employed 4,000 people. And the girls school, which had two live-in maids when she was a student, is now decrepit, its entry gates covered in rust.

Musarrat had gone home, albeit in a way she’d never imagined—and more importantly, future generations could learn from the history she’d experienced. She says they’d never understand, though, what it was like to see it happen in real time, to know the people who’d lived, fought, and died during Partition.

“An era,” she says, “has gone by.”

The National Geographic Society, committed to illuminating and protecting the wonder of our world, has funded Explorer Sparsh Ahuja's work with Project Dastaan. Learn more about the Society’s support of Explorers.