Who really invented television?

The breakthrough is often credited to Scottish inventor John Logie Baird—but the real history is far more complicated and collaborative.

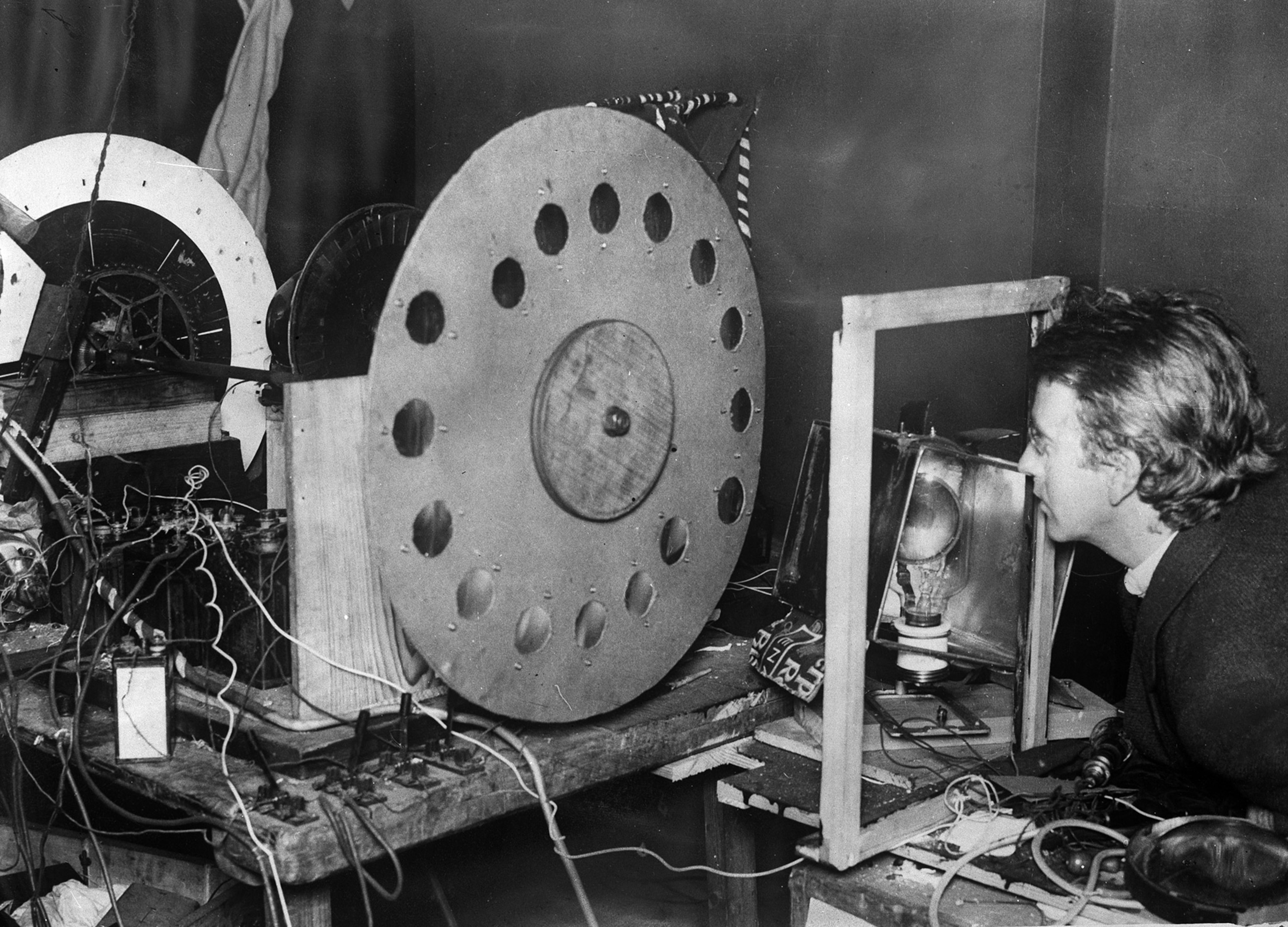

On January 29, 1926, scores of scientists gathered in a cramped London lab. They were there to see something entirely new: a blindingly bright apparatus featuring neon lights, wire, and gears at one side of the room, a thick glass screen at the other. Suddenly, the glass screen came to life and the vague, flickering image of a moving ventriloquist’s dummy materialized before the viewers’ astonished eyes.

As the blurry image of “Stooky Bill” flashed across the small screen, Scottish inventor John Logie Baird triumphed at his “Televisor.” While the picture quality was less than impressive by modern standards, it was proof of concept that live images could in fact be transmitted through thin air.

Baird had just demonstrated a technology that would go on to change the world: television. But television’s birth was more complicated than a single breakthrough. Across Europe and the United States, other investors and companies raced to develop similar technologies around the same time, laying the groundwork for what would become one of the most influential media forms of the modern area. Here’s why it’s hard to pinpoint a single inventor of television—and how it became a bona fide cultural force thanks to technological advances and social change.

The early technologies that led to television

The concept of television, and the term itself, were coined long before the technology as we know it became possible. Spurred on by 19th century developments of the telegraph, telephone, and motion picture camera, engineers turned their attention to finding a way to transmit images instead of sound.

Science had shown in the late 19th century that the element selenium could convert waves of light into electrical impulses, which presented the potential of transmitting live images. But the first selenium “cells” weren’t powerful enough to generate a large enough current to transmit effectively. And even if they had been, the electrical system then in existence was not powerful enough to transmit enough data to form a moving picture.

One idea, developed by German inventor Paul Nipkow, involved a theoretical mechanical television that used perforated discs, lenses, and selenium “cells” to film an object, project it, and turn it into an electrical current. The disc “scanned” the image as it rapidly rotated, turning it into tiny points of light that would then be assembled into a complete image upon reception. But though Nipkow patented the idea in 1885, it was hindered by a variety of technical factors.

In 1900, Russian electrical engineer Konstantin Perskiy even coined a term for the not-yet-feasible tech: “television,” which combined the terms for “to see” and “distance.” But though he presented the word to an audience of fellow engineers in Paris that year, the issue of transmission remained.

(Read more about the Hollywood star who helped invent Wi-Fi.)

It would take a few more decades for inventors in Russia, Germany, the United States and elsewhere to create the precursor technologies that would finally make TV feasible.

The first television demonstration in 1926

It all came together in the 1920s, when Scottish engineer John Logie Baird began experimenting with some of Nipkow’s ideas. As historians Jan van den Ende, Wim Ravesteijn, and Dirk de Wit write, Baird’s invention “turned Nipkow’s on its head,” switching the position of the light source and the photocells to illuminate the object bit by bit.

Though the technology was still crude, it worked. On January 26, 1926, Baird demonstrated his machine, which he called the Televisor, in a London attic to 50 scientists and a newspaper reporter.

“They didn’t believe it,” Baird’s assistant, Andy Andrews, recalled in a BBC interview decades later. “The pictures were a bit of a blur, but it was amazing,” he added. “They were all absolutely flabbergasted by it.”

The technology was impressive for the time. “The image as transmitted was faint and often blurred, but substantiated a claim that…it is possible to transmit and reproduce instantly the details of movement, and such things as the play of expression on the face,” wrotea reporter from The Times a few days after the demo. Within months, Baird was broadcasting regularly from his London lab on radio frequencies whose programming had ended for the night.

Baird’s invention overlapped with other television devices like American inventor Charles Francis Jenkins’ “radiovision,” which he first demonstrated in 1925, and large companies like AT&T and Westinghouse began developing their own mechanical televisions. As a result, Logie is considered just one of television’s many inventors. Instead, historians believe the invention of TV was a process involving concurrent inventions with different approaches.

Mechanical televisions eventually faded in the 1930s thanks to newer tech that made electronic televisions possible. With names like “Iconoscope” and “Emitron,” these devices used electron beams instead of selenium to capture and transmit moving images. Television operators began seeking, and receiving, licenses in a variety of countries.

How television became a global cultural force

Though high-profile experiments like Baird’s drove public interest in the new technology, TV sets were expensive to produce and only a few television stations were set up between 1926 and the 1940s. World War II disrupted production of television sets, and television remained a relatively niche interest. According to the Radio Electronics Television Manufacturers’ Association, there were an estimated 44,000 TV sets in the U.S. in 1946.

But a boom in industrial capacity and an interest in the technology helped TV blossom in the years after the war. Soon, stations abounded, and by 1952 there were an estimated 24.3 million TV sets and 225 stations in the U.S. alone, according to RETMA figures.

More TV sets and stations meant more chances to watch television, and TV broadcasters soon began presenting shows that used similar formats to those familiar to radio listeners. News programs, soap operas, variety shows, and teleplays began changing the way people consumed information and entertainment. Reluctant actors and producers soon realized the medium was a force to be reckoned with and flocked toward television. Broadcasters created new formats, like the situation comedy or sitcom, to meet the moment, and advertisers rushed to get their products on TV.

(This strike threatened to cripple Hollywood in 1960.)

Now cheaper and available in virtually every home, television created a true mass media audience that could bring products, information, and cultural messages to people in their own home. As audiences, innovators, and artists rushed to take advantage of the new medium, television entered what is now known as its golden age in the 1950s.

It’s been a long, complex journey ever since. In 2024, industry group TVB estimated, a whopping 96.8 percent of American households had a television, down from a peak of 98.9 percent in 2011. Today’s TV is changing again thanks to smartphones and consumer trends. But though the images on modern screens are a far cry from Baird’s two-inch “Televisor,” they owe much to the inventor and his counterparts—proof that potent things can come from humble places.