For those in long-term care, COVID-19 compounded the weight of grief

Even as vaccinations make their way across the United States, the impact of the pandemic remains present for residents of long-term care and their loved ones.

When Kevin McCauley's roommate died from COVID-19 just before Thanksgiving last year, McCauley lost someone he considered a brother. With his sister living 1,500 miles away from Albuquerque Heights Healthcare and Rehabilitation Center, friends like Michael Lazarin were there to share holidays, pizza, and conversation. With the privacy curtain between their beds pulled back, they’d face each other in their wheelchairs and share stories of their time as mechanics at Lincoln Mercury and Ford, their past romances, and the loss of their parents.

“We knew more about each other’s family than we’d care to know,” says McCauley, 58.

Even as they watched news of the pandemic unfolding on their individual televisions, McCauley and Lazarin thought the virus would “bypass” them. Their long-term care facility had strict quarantine. During outbreaks, they had to be confined to their rooms for two-week periods.

“They shut that door for 24 hours and you’re not allowed to go outside. That is worse than a prison,” says McCauley. “They had to do what they had to do.”

According to data from the New Mexico Department of Health, 55 residents of the facility contracted the virus and eight died.

Since Lazarin passed away, McCauley takes his grief, and a toolbox full of cigarettes, to an outdoor patio where a “smokers’ club” comes together several times a day. Together they remember and grieve their isolation, fears, the loss of simple pleasures, and the death of loved ones.

Losing a spouse

Among those taking part in the patio ritual is Ronda Crew Dunham, 54, who lost her husband to COVID on May 10, 2020. He died at a VA hospital after contracting the virus at another assisted living facility. Crew Dunham had moved into Albuquerque Heights in 2019—thinking it would be temporary—to get help stabilizing her seizures. Her husband’s son was unable to care for his father and placed him in an assisted living facility nearby. Twice a week Frank Dunham would be brought to Albuquerque Heights to visit his wife. “We always promised each other that we wouldn’t let each other die alone,” she says of her husband. “But nobody saw COVID coming.”

Crew Dunham has yet to weep for her loss. But multiple times a day she still reaches for her phone to call Frank, yearning to speak to him for hours, as they used to do. "You’d think after 20 years you’d have nothing to talk about,” she says. “Not true.”

Those who have lost loved ones to COVID-19, as well as those who’ve experienced a death during the pandemic, are at greater risk of suffering “prolonged grief” due to the lack of traditional rituals, says Dr. M. Katherine Shear, director of the Center for Complicated Grief at Columbia University in New York.

“The circumstances of the deaths always matter,” she says. “Losing someone is one of the most stressful things we can experience.”

Crew Dunham often ruminates about the circumstances of her husband’s death. Had she been able to be with her 72-year-old husband when he fell ill, perhaps she could have convinced him to reverse the Do Not Resuscitate order on his advance directive. She found out her husband had tested positive for the coronavirus shortly after he was admitted to the VA hospital. By the time she got on a video call with him, he was already heavily medicated and unresponsive. He died two days later.

Since her husband’s passing, Crew Dunham has been joining the smokers’ club on the patio. “I feel safe here,” she says of the facility. “We are each other’s family."

Support group connections

John Olinger, a 95-year-old World War II veteran, worried that the staff could bring the virus to him, breaking up the bit of refuge the patio gathering provides. “The group outside, that’s a big help,” he says. “I hope nothing happens to cut it off.”

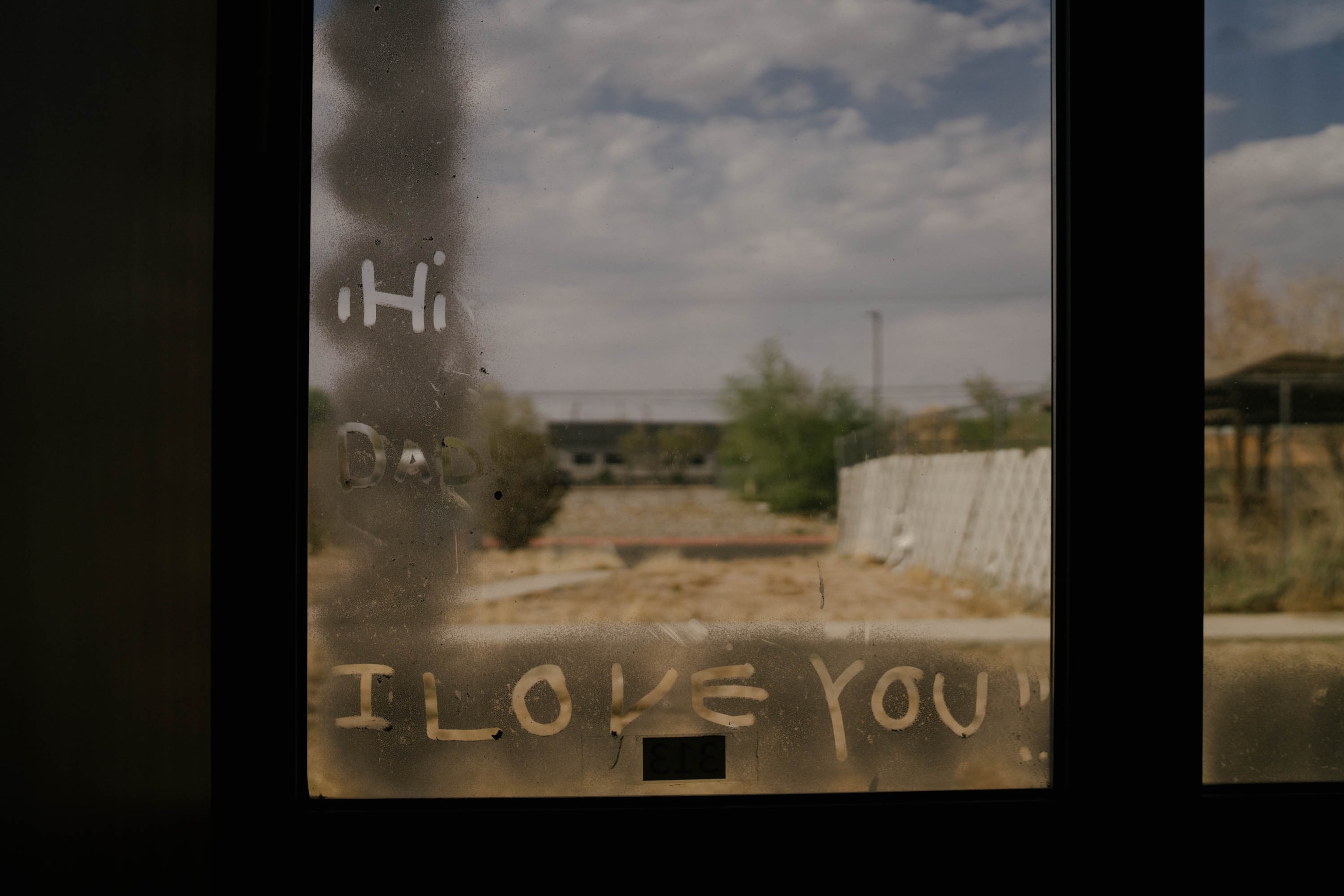

Families have yet to come back inside this facility. Following state and federal guidelines that suggest outdoor visitation, each family member receives a monthly, one-hour supervised visit on the patio of the long-term care wing. In the memory care wing for those with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, families visit through a window for 30 minutes a week and once a month on the patio. The New Mexico Aging and Long-Term Care Services Department and Department of Health let facilities determine frequency of visits. On April 26, one resident in the short-term care unit tested positive for the virus, which caused visitation to be temporarily suspended, but has since been restored.

Activities like bingo, crafts, and monthly birthday parties in small groups also have resumed. But residents are still prohibited from leaving the facility for lunch with a friend at Applebee’s or for a trip to Walmart.

“It has been 400 and some days since we’ve seen the parking lot,” says McCauley.

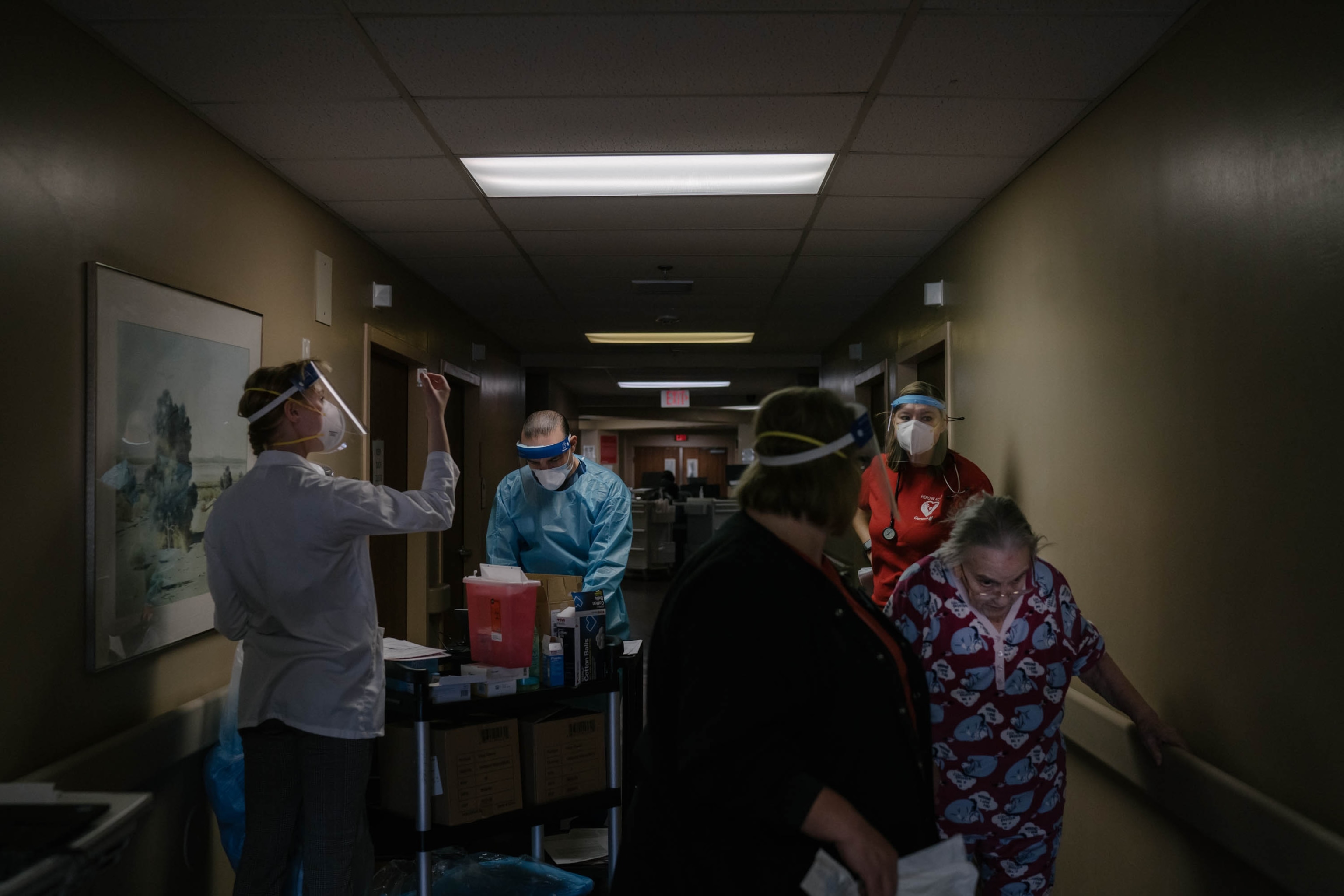

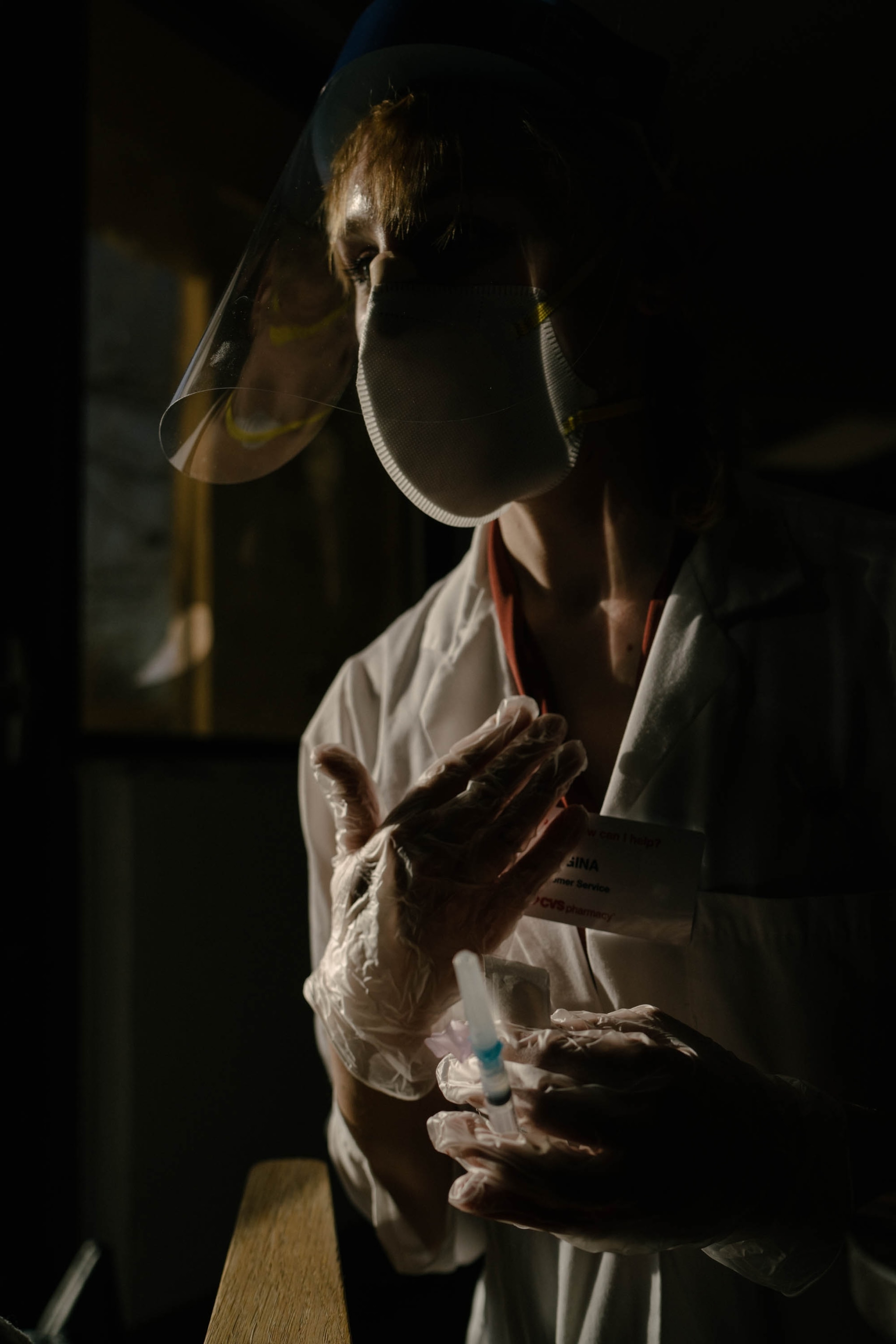

COVID-19 vaccinations

Currently, 50 percent of the 117 Albuquerque Heights residents and 48 percent of the 136 staff members are vaccinated.

When McCauley received his first dose of the Moderna vaccine on January 7, he experienced survivor’s guilt: He got protection against the same virus that killed his roommate. Lazarin had been infected twice, but McCauley never tested positive.

“It was a big sigh of relief,” says McCauley of the shot. “There is also guilt when you're still alive and someone you know is dead because of a certain virus.”

Studies estimate the mental health fallout of the pandemic to be three times the medical impact, but some states have yet to provide emotional support guidelines to long-term care operators, experts say. And efforts to keep people safe could have been detrimental for some.

“The confining residents to their rooms and safety measures that were taken to keep people safe from COVID could have very easily re-traumatized people or even newly traumatized people in different ways, particularly that isolation piece,” says Dr. Nancy Kusmaul, associate professor of Social Work at the University of Maryland Baltimore County, who focuses on long-term and trauma-informed care.

“It stinks to be shut in your room all the time,” says Donna Arthur, a retired nurse and ordained Christian minister. “I’ve always been a people person.” When feeling depressed, she leans on her faith, her sense of humor, and wisdom from her career in healthcare as a nurse.

“Whenever I’m blue, I talk to my best friend, God,” Arthur says, as she looked out at the Sandia Mountains beyond her window. “In nursing, I realized that the geriatric group had so much to share, but no one had the time to listen.”

Dementia and Alzheimer’s amid COVID

When Angie Burnside kept seeing her mother Annie Burnside weave and undo her work at the loom three years ago, she knew something wasn’t right. Then one day Annie wandered out of her house in Crownpoint, New Mexico, an area that’s part of the Navajo Nation, into the wilderness. It took her children hours to track her down. In April 2019, Annie, who speaks only Navajo, moved into Laguna Rainbow, a skilled nursing facility for Pueblo and Navajo Indian elders. But even there her wandering continued.

In August 2019, after Annie was found walking toward Mt. Taylor in an attempt to find her home, officials at Laguna Rainbow told Annie’s 11 children that they couldn’t serve as a “private security guard” for their mother. So she was transferred to Albuquerque Heights, where she is the only Navajo-speaking resident with Alzheimer’s.

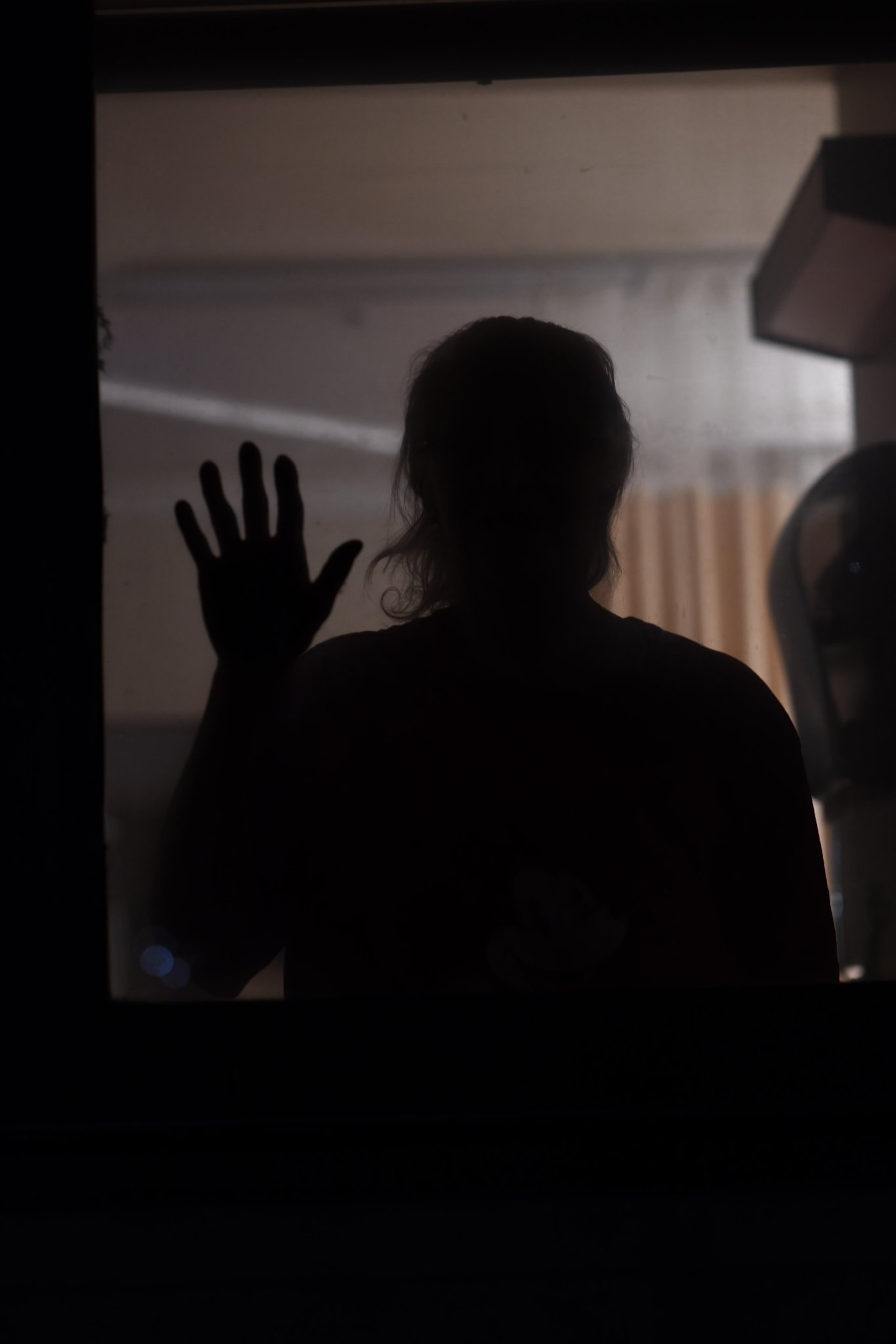

Frequently, Annie pushes her walker toward one of five locked doors, hoping to escape to her property in Littlewater, New Mexico, where she spent years working in a corn field, tanning animal skins, and taming horses. Some moments she believes that her husband, who passed away in 2014, will come and get her so they can walk down a mountain to their other property in Crownpoint. With her hands on the door, Annie pushes and pushes on the glass that separates her from the patio and parking lot.

Before the pandemic struck in March 2020, seniors experienced grief as they entered long-term care. Some, like Annie Burnside, had lost their spouse, home, community, belongings, and cognition. Many lost friends, mobility, and finances.

Dr. Kusmaul of the University of Maryland, and others studying long-term care, call this “disenfranchised grief,” a hidden grief unacknowledged by social norms.

“The amount of loss that’s there at baseline is huge,” she says. “And then you add the loss, the losses that have come over the last year.”

Well before the beginning of the COVID-19 restrictions, in an attempt to protect her from walking along the Interstate-40, Annie Burnside was shut off from the life she had known for 87 years. When the restrictions were put in place, what already felt like confinement became overwhelming for those with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

“It’s painful,” Angie Burnside, Annie’s daughter, says of her mother’s separation from her children. “But she needs a lot of care.”

Dana Cox saw a shift in her dad’s mood and cognition during their weekly video calls where her father, Thomas “Dan” Langdon, who is a Vietnam veteran and a former sheriff’s detective, would ask why he and other residents were wearing masks.

“He would realize that something was going on. The atmosphere had changed. It wasn’t as calm as it had been,” says Cox. By August 2020, her father also began struggling to remember that Cox was his daughter.

Barbara Mendez Campos, a licensed clinic social worker with the Memory Disorder Clinic in Orlando, Florida, says Langdon’s reaction is typical. During the past year, she noticed changes in mood and motivation and an increase in emotional crises among her clients with dementia at 12 care facilities. “Behaviorally, a lot of people with memory loss tend to mimic what is going on,” says Mendez Campos. “We saw a lot of anxiety rise. We saw a lot of depression rise. We saw a lot of memory disorder related delusions.”

Dr. David Bullard, a clinical psychologist in San Francisco who specializes in trauma, says that even when the brain falters trauma lives in the nervous system without an associated mental recollection: “Just because you don’t remember, doesn’t mean you’re not affected by it,” he says.

Nearly everyone in the dementia and Alzheimer’s unit at Albuquerque Heights contracted COVID-19. Getting residents to remember to wear masks, maintain social distance, and remain in their rooms was a challenge.

Annette Arvizu’s husband, Salvador Arvizu, was among those infected. Having to visit him behind glass was heartbreaking. On one of the visits when Salvador was in the COVID-19 isolation wing, Annette took a close-up photo of his face with her phone, thinking it would be the last time she would see her husband of four decades.

“That is when I really lost it,” she says.

Salvador Arvizu, who worked in the dairy industry for most of his life, moved into long-term care in 2019 after he stabbed Annette during their weekly Friday night gathering over drinks. Annette recalls seeing a gradual decline in Salvador’s memory over the past decade, but he had never shown signs of violence. Annette was fearful for her husband’s safety and that of those around him. “He was a kind, gentle, loving man, and the next minute he is in no man’s land.”

After moving her husband into long-term care, Annette spent every day from eight in the morning to two in the afternoon helping Salvador shower and dress and trying to encourage him to eat his meals. That ended after the pandemic kicked in during March 2020.

“It’s not just traumatic for them. It’s traumatic for the whole family,” she says of the past year. “He’s there and all of a sudden, after 43 years, he is not.”