The Louvre has a wild history of being robbed in broad daylight

One of the most infamous heists in the cultural institution’s history was the 1911 theft of the Mona Lisa—when Pablo Picasso numbered among the suspects.

It took just seven minutes for a group of audacious thieves to pull off what may have been one of the most daring crimes in modern art: the theft of Napoleonic-era jewels from the Louvre in Paris on the morning of October 19.

The heist, which took place while the museum was open to the public, involved a variety of jewels once owned by members of the French monarchy, including an emerald necklace and earrings that Napoleon gave his second wife Marie-Louise for their wedding. Now, questions are raging about how masked men could successfully evade security and nab priceless objets d’art from one of the most important art institutions in the world.

It’s far from the first time. The museum has a longstanding history of shocking break-ins and unsolved thefts—despite being built precisely to protect the nation’s cultural heritage in the wake of a bloody revolution.

Though the Louvre palace dates back to the 13th century, the museum was founded during the French Revolution, a time of fervor for both egalitarian museums and political systems. In 1792, violent insurgents stormed Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette’s royal residences and declared a republic. Suddenly, the monarchy’s entire art collection belonged to the new state—and were under threat from looters who wanted to seize or smash all traces of the French monarchy.

(This is what happened the last time the French crown jewels were stolen.)

The museum at the Louvre would safeguard state property amid the chaos of the revolution, as well as showcase a newly democratic France’s most prized treasures.

But its cultural keepsakes have long proven tempting to would-be art thieves, and over the years the museum racked up a long list of security problems, and thefts.

Here's the story of some of the museum’s most audacious crimes in the last century—nearly all of which have taken place during broad daylight.

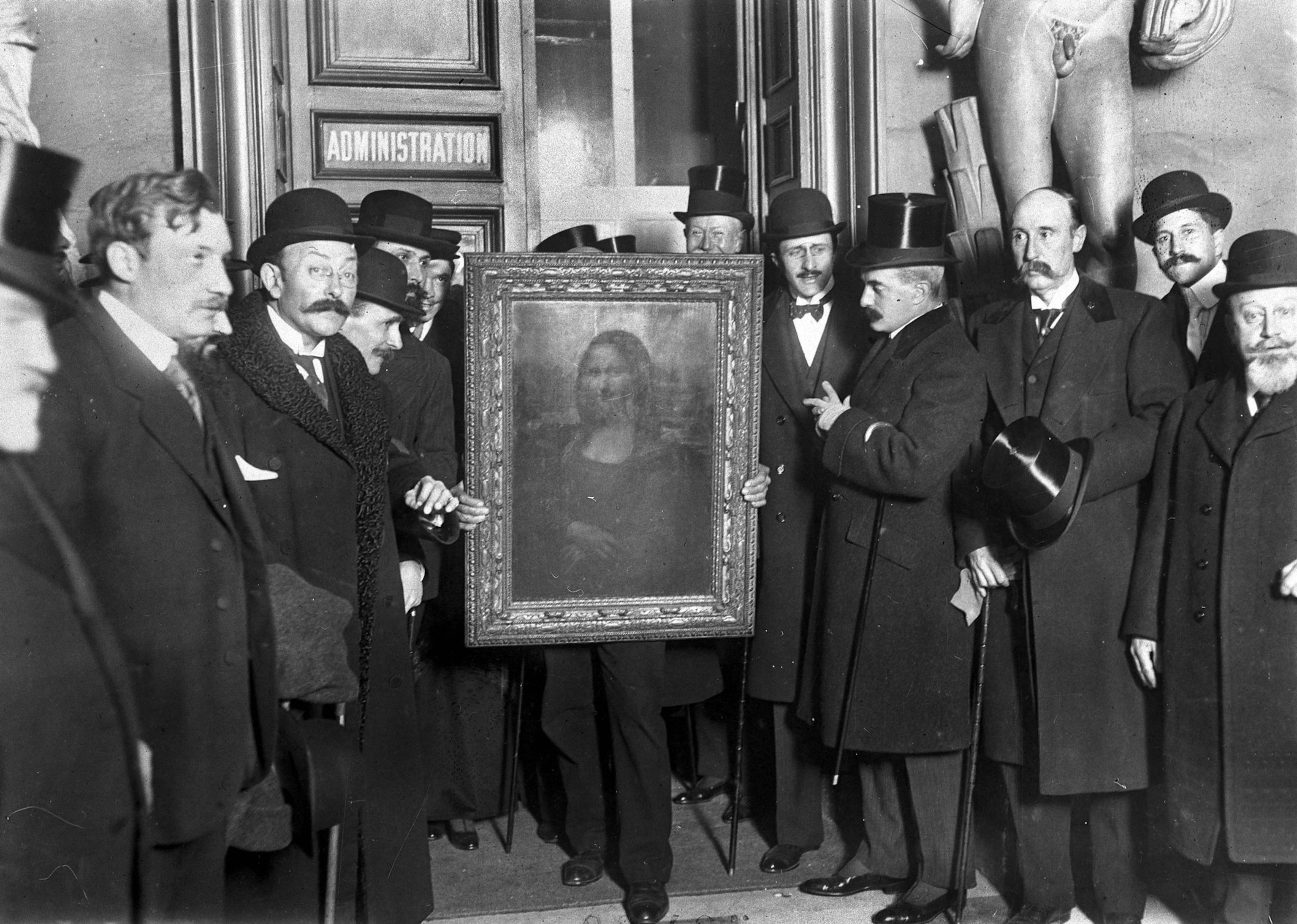

The 1911 Mona Lisa heist

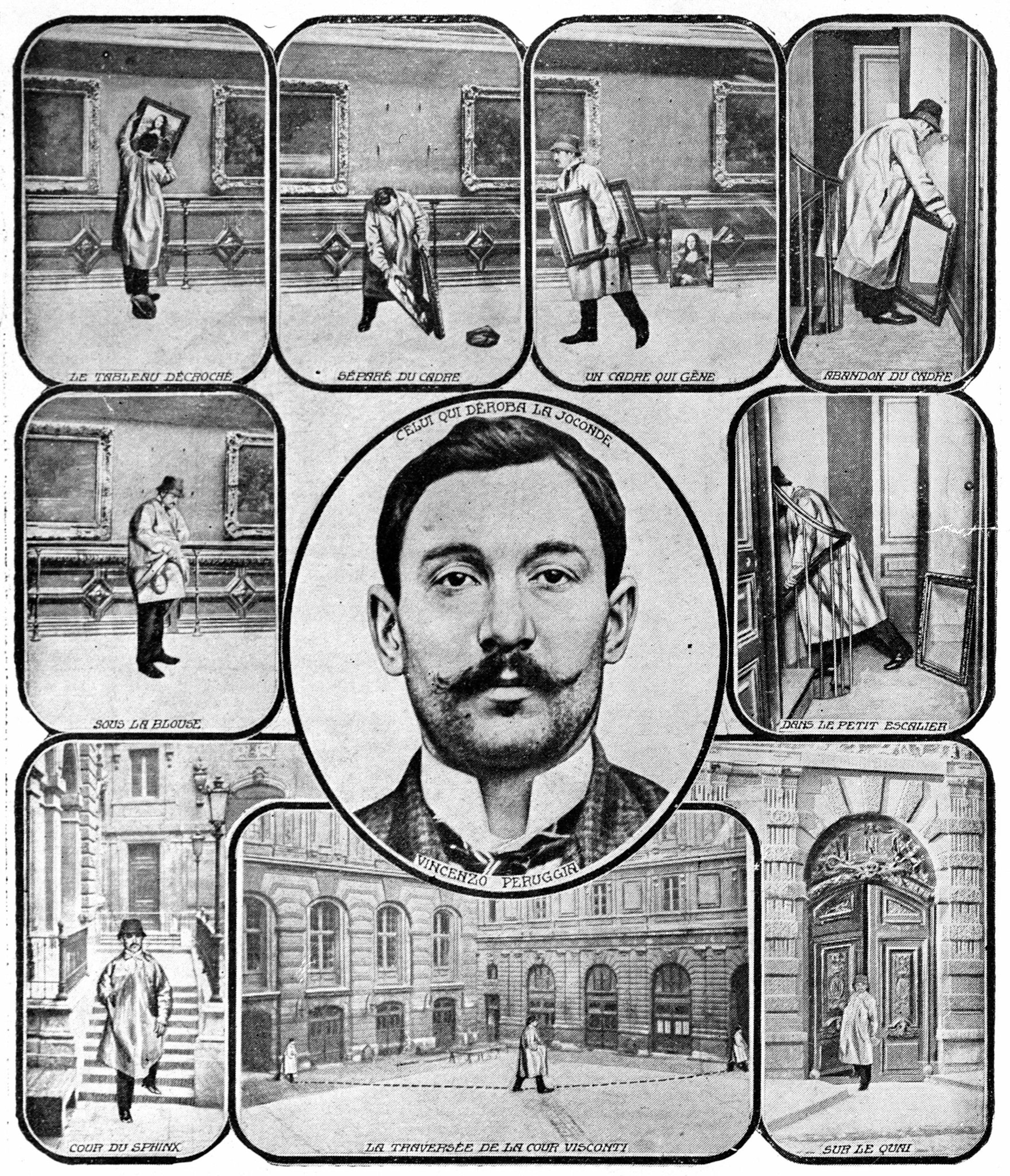

The shocking theft of the “Mona Lisa”—then a lesser-known work by Leonardo da Vinci—occurred on the morning of August 21, 1911. It was a weekday, and Vincenzo Peruggia, an Italian immigrant who had briefly worked at the museum building frames and cases, dressed in his old work uniform and walked into the Louvre unchallenged.

At the time, the painting was hung on a wall in the Salon Carré, but it was the norm for paintings to be briefly removed for conservation or photography. So no one noticed the painting was missing until more than 24 hours after Peruggia walked out of the museum, the painting beneath his smock.

The crime was only discovered once a wealthy patron showed up at the Salon Carré to work on a painting of the gallery. All that remained of the Mona Lisa were the hooks that had affixed its special case—one Peruggia almost certainly constructed himself—to the wall.

The manhunt that followed was massive in scope—and, as historian Aaron Freundschuh wrote in a 2006 article in the academic journal Urban History, “fantastically fruitless.”

One of the strangest turns in the investigation involved a young Pablo Picasso, who was briefly questioned on the art theft. Though Picasso did not steal the Mona Lisa, it was revealed he had ties to an earlier Louvre theft: He had purchased a pair of ancient Iberian statue heads that had been stolen from the museum a few years earlier, and he surrendered them to the police for fear of prosecution during the Mona Lisa case.

The Mona Lisa was only recovered in 1913, when Peruggia attempted to sell it to another museum. It turned out Peruggia had been hiding the painting in his Paris apartment. During his trial, Peruggia claimed he’d stolen da Vinci’s painting as a patriotic gesture toward his home country Italy, though the painting had actually been completed in France and purchased by the French monarch, Francis I, in 1518. Meanwhile, the theft boosted the painting in the public eye, turning Mona Lisa into a household name.

The Nazis try to sack the Louvre

The Nazi occupation of France in 1940 threatened some of the most significant cultural losses yet: A portion of the Louvre’s collection looted by occupying Nazis.

But the Louvre’s director had a plan: Before Paris fell to Nazi Germany, Jacques Jaujard saved much of its collection, transporting over 1,800 wooden cases of precious art into the countryside. Most of the museum’s artworks made it safe and survived the war, and when the Nazis marched into Paris in 1940 they found a mostly empty museum.

However, high-level Nazis did get their hands on several of the museum’s masterworks, like Bartolomé Estaban Murillo’s “The Immaculate Conception of Los Venerables,” which was given to fascist Spain in a 1941 exchange.

And they looted many artworks from French citizens—displaying those in the now-empty Louvre.

A string of art thefts in broad daylight

Security problems continued to plague the museum after it reopened in the wake of World War II. There was the 1966 theft of antique jewelry as it was being transported back to France after a loan to a Virginia museum. The jewels were recovered after being found in a grocery bag in New York.

In January 1976, burglars stole a Flemish painting from the museum, and in December of the same year, masked men burgled a jeweled sword once owned by French King Charles X, accessing the museum from a second-floor scaffold. The sword has yet to be recovered.

There was another string of thefts a little over a decade later. In 1990, thieves took a small Renoir painting from the Louvre—cut from its frame in broad daylight and stolen along with 12 pieces of ancient Roman jewelry and a few other paintings. Five years later, two objects were stolen in a single week. And in 1998, a Camille Corot painting was cut from its frame and disappeared. It has yet to be recovered.

Since then, the museum has attempted to boost security amid widespread criticism, even undergoing a recent security audit, according to Reuters.

Will the priceless jewels ever be recovered? According to the Associated Press, just one of the objects has been found thus far—a glittering and now broken tiara of emeralds and diamonds once gifted by Napoleon III to his wife, Eugénie. But the fate of the other artworks, which includes jewels worn by multiple French queens and empresses, remains uncertain.

Even if they’re not recovered immediately, however, history shows there’s hope they could someday make it back to the museum: In 2021, a suit of Italian Renaissance armor that had been stolen in 1983 was recovered from a private family collection in western France.

In the meantime, the Louvre's long history with audacious thieves—and the debate about how to secure France’s national treasures—seem destined to continue.